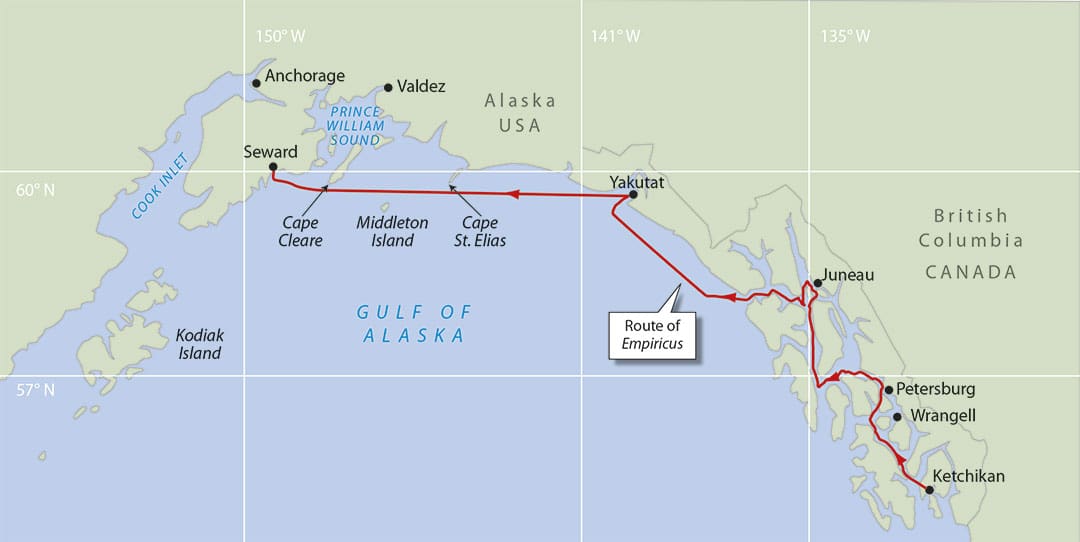

My young sons and I were about to sail my 50-foot yawl, Empiricus, from Ketchikan to Seward, Alaska. Moving back to my hometown of Seward from my current home in the southeast part of the state with my boat would mean crossing the Gulf of Alaska.

“It’s just wind and waves out there, boys,” I assured my sons: Isaac, 10 and Steven, six. “We just have to keep the ocean out of the boat and stay onboard. We’ll be fine.”

This would be my first time out of sight of land. Beyond the ripping tidal currents of the inside waters of Southeast Alaska. Free from looming shoals, williwaw winds and blinking buoys.

Empiricus, with her heavy displacement, gaff rig and narrow beam was well-suited to offshore passages. Her prior owners had sailed her to the Christmas Islands and back. It was her current crew that was green.

Our route covered approximately 715 nautical miles including the final leg, a 410 nautical mile stretch of open ocean.

Wrestling, wind and the weather wizard.

The boys and I departed the Ketchikan fuel dock on July 29 at 15:29. We motored and sailed up the inside passage stopping in Petersburg, Juneau and a number of other anchorages along the way. West of Juneau marked the end of familiar waters for me.

As we got closer to the Gulf crossing my mind spent increasing amounts of time rehearsing about a place I had never been — over the horizon, where the earth’s curve is greater than the mountain peaks.

As a competitive wrestler in high school, I learned how to wrestle a match before it happened, in my imagination. By formulating scenarios and then visualizing my actions for each one, I could go into competitions where no matter what happened during the match, I had a second-nature response.

So, I did that now, ignoring the fact that when I wrestled at the national tournament, I lost every match. That was a whole new level for me — and so was this ocean passage. The moves of the ocean were of the variety I had never seen. We sailed, we motored, and I wrestled on in my mind.

I understood the problem well enough but lacked experience — and sailing with me was precious cargo.

My number one concern was weather. Calm weather means no wind. No wind means more fuel. More fuel means a longer trip, since detours to shore for fuel add miles. A longer trip also means more time “out there” away from resources. Getting a “weather window” with enough wind to power the boat but not so much that the sea state is hazardous was the ticket. I wanted an epic trip, but without getting thrashed in the process.

By August 7, we had made it to Elfin Cove, a tiny fishing town perched just inside Cape Spencer, on the edge of the Gulf of Alaska. We moored to the fuel dock at 20:25 and took 21.9 gallons of fuel.

Once we fueled, I sparked up the weather channel. We listened to that crackling robotic voice which held us in thrall, awaiting good news, like seekers of the Wizard of Weather-Oz.

The Great Wizard came through with a bonny forecast: seas less than eight feet and winds less than 20 knots, which was my threshold to depart.

The plan was to aim for Resurrection Bay, favoring the north shoreline to hold the port of Yakutat as an option. The boys would take turns holding a watch and steering. I planned to live topside for the duration of the voyage. If we ended up motoring a lot and needed more fuel, or if a big storm was coming, we could pull into Yakutat, fuel up and wait it out. Stopping in Yakutat adds at least a full day and 100 miles, depending on your course. But it’s a safe harbor on a stretch of coastline with few safe harbors.

Once past Cape Spencer, the entire coastline of the Gulf is a rocky, lee shore with only a few possible hiding places for foul weather, most of which are tide-dependent. One such hidey hole is Lituya Bay. In 1958, a local landslide created a 1,719-foot tsunami, the largest ever recorded, killing five people in the bay and launching others over the bar into the ocean. Entrance into Lituya Bay is narrow, with safe navigation through the entrance only possible at slack tide in calm weather.

We had 410 nautical miles of open ocean to cross to reach the mouth of Resurrection Bay, and at least 130 nautical miles to make the turn into Yakutat Harbor.

We would depart in the morning, leaving us the evening to explore Elfin Cove. Plenty of time, as the entire town covers about a quarter mile, all accessed by boardwalk. It doesn’t get dark in Alaska in mid-summer, so people were out and about late into the evening. There are no roads, and no motorized vehicles there. We visited the library, a little tiny house that used to be the schoolhouse. No families lived in Elfin Cove anymore, and there were only about six year round residents. The old schoolhouse was just one room, and now was full of books, laid out on tables, for free exchange. The fuel dock lady said we could stay overnight if we slid forward on the pier and left early. No problem!

The next morning at 08:50, early enough for Elfin Cove, Isaac belted out “Bow line is free!”

Steven pulled in the stern line and we were off, skating our way between islands on glass calm water.

By 10:00 it was Isaac’s watch and we were feeling the smooth sea lump under our feet as we left Cross Sound. While he steered for the cape in calm air, I recorded our position (58° 14.6’ N by 136° 52.8’ W). We cleared the shoal waters of Cape Spencer by less than a mile.

Ugh and awe

With Cape Spencer to starboard, the lump increased with headwinds stacking the tops up. Under staysail, main and mizzen, we bore away, putting Japan dead ahead as the course to steer while we got some distance from the North American continent. We held a close reach and added some engine to gain sea room.

At noon Steven was on watch and by 13:00 the engine was off. By 18:30 we were south and west of Lituya Bay, having sailed and motored for max speed. I had already decided to pull into Yakutat which meant I could burn a bit more fuel to hedge our bets.

The boys were experiencing a thing we call type two fun. That’s the kind of fun which is fun when you look back on it, but during the experience is a mixture of ugh and awe.

The comedy ensued as the watch schedule collapsed. At one point I sent Steven down to wake Isaac for his watch. Twenty minutes later I stuck my head down the companionway to find Isaac had silenced his human brother alarm clock by tying him to the mast and lying back down.

Steven, half-laughing, half-whimpering, emerged from his cocoon and eventually Isaac was back on watch wearing all his gear and a sheepish grin. Steven was out cold until evening.

Late that night the winds were gentle as was the sea. We were drawing nicely under full sail in the pitch-black night on a close reach, port tack. Splashes off the bow told me Dalls porpoises were swimming with us. I had enjoyed seeing them many times, but never like this. The porpoises were scattering bioluminescence in their wake. Bioluminescence is caused by tiny creatures like fireflies of the sea that emit a greenish light when disturbed. Depending on the concentration they can be sporadic blinks or constellations in the water. On this night, they were as thick as the water itself.

With the mizzen set, Empiricus steered herself while we all went to the bowsprit, watching the porpoise fly beneath our feet, like jet fighters dogfighting the bow for fun. This way and that they darted with incredible speed and grace. Deep under the bow I could see them, cloaked in a green jet stream so bright I could make out the details of their lines. Even their black and white color scheme was lit by the bioluminescence.

Every few seconds fast fins ripped the surface, spilling green foam into the air and reminding us that we were not underwater with them but above water, looking through a window to an unforgettable exchange between worlds.

The last green torpedo launched out of sight and the wind died. Stuck in the moment and appreciating the still-clear forecast, we did not start the engine. Instead, we hove-to on an offshore tack and slept about 12 miles southwest of Dry Bay.

At 07:15 on August 9, we fired up the engine, having made about two nautical miles westward overnight. By 10:00, we were making seven knots under a full mainsail alone. I look back on my logs and wonder how I went anywhere without reefing skills. I was still in that commonly accepted but dismally inadequate way of thinking that when the wind blows too hard, you just take the sails down. Now, I teach all new sailors reefing skills as an elementary task, not just for “advanced” sailors.

We kept hauling the mail under sail and by 15:00 we were rounding Ocean Cape and the entrance to Yakutat. It takes forever, seemingly, and I was tempted to cut the mark as it appears to be in open water, but I held the proper course and followed the red right returning buoys. Only locals in shoal draft boats cut the mark — check out the chart and you will see why.

Yakutat is a cool place. We spent all day going to the store and just messing around. A stray dog followed us around most of the day. The boys called him Bacon, since that’s what we fed him from our breakfast. We made up goofy voices for him which mostly involved him wanting some more of our bacon. The boys were hysterical in laughter and high on life. It was a fantastic day.

That day was followed by a fantastic forecast and that night at 11:00 we steamed out of Yakutat for the open sea. Just 300 nautical miles to Seward.

Our course would carry us 30 to 50 miles offshore and out of sight of land.

Mystery boat

At 01:00 we stopped and drifted for some sleep just southwest of Icy Bay. At 05:40 we fired up again. No wind. Motoring.

I kept my fuel burn estimate running in the log, concerned always about having enough. I wanted wind, but not too much wind. To maximize efficiency, we sailed when it blew and motored when it didn’t. I found a tear in the leech of the main and tried my hand at a herringbone stitch near Cape St Elias of Kayak Island. Working through my copy of The Sailmaker’s Apprentice with my palm and thread, I reattached the hem of the leach to the panel. I had confidence my stitches would hold, but the cloth was brittle. Another concern for me if the wind got too high.

Steven was at the helm one night and very tired. His little eyes could see just dead level to the compass through the helm spokes. I was working to trim the mizzen and though he was nodding off, I didn’t know it. When the jib backed, I barked, “Hard to port!”

Steven threw the helm spoke right into his own head and started crying. I was asking a lot of him at six years old and I felt like a jackass.

“I got it buddy, go get some sleep.” I said as I relieved him at the helm.

My method for sleeping, before I discovered proper jacklines, was to tie a line around the waist of Isaac or Steven to a cleat and then tie myself to a cockpit cleat right next to them. They could wake me if they needed.

But I learned something. “If they needed” was a relative term. Once I woke feeling surprisingly rested. Isaac said, “There was a boat coming so I went around them.”

I sprang up and whipped my eyes around. No boat.

“It was a while ago,” he continued.

“Gooood! Good job!” was my heart-thumping reply. Angels must have been around.

I asked Isaac more about the boat, hoping it was miles away. He was upset, not about seeing it or the maneuver, but because he thought it looked abandoned. He was worried that there might be people onboard the drifting boat that needed help. But he said he didn’t want to wake me up for that.

In full admiration of Isaac’s maneuver, I was tempted to go searching for the mystery boat, both to help people possibly in need and to claim salvage rights if it was indeed abandoned. But with no mast on the horizon, many miles to go and good weather, we pressed on homeward.

Lessons learned

After a few hours of close-hauled sailing, making better than five knots, we hove to outside the shipping lanes of Prince William Sound for a nap.

Our next sailing session was a lesson in gaff rig handling. After a nice run wing-on-wing with a poled-out Yankee, the wind died off quickly, leaving a lumpy sea, which took the gaff, then the boom into a crash jibe, slamming the main into the running backstay with a shudder. Nothing broken, lesson learned.

Montague Island was the next sweeping land mass to encounter. We could get weather from the radio off Cape Cleare. As we approached the shallow waters near the Cape, the forecast remained good but there was no wind. We still had plenty of fuel, which eased my worries. We stopped to try to catch a halibut. Nothing bit our hook, so we turned in and slept hard until 06:15 on the 13th. I looked at our position. We had drifted 7.4 nautical miles along our course. Awesome!

We had 35 nautical miles of sea and one more cape to round before we would be inside Resurrection Bay. We motored about half of that then the wind piped up and we sailed wing-on-wing for Cape Resurrection. I could hear charter captains out fishing on the radio. These were the people I grew up with. I had been away for a long time. When I left, sailing was but a vapor of a dream in my mind. Coming back this way felt triumphant and our early celebration became a distraction that led me to a mistake.

I decided that cutting between Barwell Island and Cape Resurrection was a good idea. The water was deep and it looked fine to me. But I knew nothing about the waters of my hometown. That place was notorious for violent wind and current shifts.

We entered the gap wing-on-wing like we owned the sea. Then, chaos, as the swirling winds off the high pinnacles of rock sent the sails flapping. The wind shifts off the cape hit every point of the compass at least twice. Isaac wrestled with the pole end to unhook the Yankee.

We kept it together, somehow, and dumped the canvas onto the deck. I fired up the engine. The wind, steady and strong outside the cape, had eased to a light breeze. Having crossed the gulf sailing every stitch of usable wind, it seemed silly now to sail in light air and fight the current. We settled in and started stowing things.

At 22:44 on Aug 13, we tied to slip E 68 without incident, and we posed on the dock for a picture.

Returning to my hometown on a 16-ton, ocean-going sailboat felt good. I felt less worried about being trapped there with Empiricus under my feet. She was my spaceship, ready to launch. I realized during that voyage that the open ocean was for me. n

Jesse Osborn is the founder of Seven Seas Sailing Logistics, does deliveries and consults with boat owners.