It was May when my wife Ellen gave me the go ahead to cross the Atlantic. In June, four short months away, my cousin Marta Downing and I would depart New England for Ireland in Far and Away, Ellen’s Cabo Rico 34.

Preparing the yacht for a transatlantic passage drew on my experience at sea (many years of coastal cruising and blue water, but no passage longer than 1,200 miles), and also on guidance from authors and sailors Eric Hiscock, Hal Roth, Bob Griffith, Don Street and many others. This received wisdom, absorbed since childhood, allowed me to do a proper job preparing Far and Away for the voyage. My priorities focused on the rig, sails, watertight integrity and steering, with navigation, weather routing and a safe and secure accommodation closely following.

Sails and the rig

Far and Away’s rig was new enough, considering usage and layups. The yankee was tired, and I ordered a new one to arrive just in time. I also added a third reef to the main, and bought a used storm trysail. Whether a trysail is necessary with modern sails is debated, but I am old school and wanted one and in any case now I’d have something to put up if the main blew out.

I pulled a chainplate port and starboard, and polished and examined them using hobbyist magnifying glasses. Both looked great, no distortion of the fastening holes, no bent bolts, and no cracks, pitting or staining. But the backstay chainplate showed evidence of a welded repair, and I asked a machine shop to fabricate another. I replaced the bolts too.

The rig was on sawhorses and I carefully cleaned each terminal of the standing rigging with acetone and inspected everything, again using my magnifiers. A tired rig will usually show signs of incipient failure, so the absence of cracks, broken strands and staining was encouraging. I cleaned each turnbuckle with diesel fuel and lubed the threads using warm Lanocote. Mindful we’d be hauling down the main in difficult conditions, I also scrubbed the sail track with detergent and a bottle brush, surprised as always at the amount of dirt that emerged, and I sprayed it with McLube Sailkote. I likewise inspected and lubricated the masthead sheaves, replaced the mast boot, and serviced the winches and the jib furler.

Watertight integrity

Watertight integrity was the next priority. Many sudden sinkings are the result of seacock failure, often from electrolysis, so I gave each seacock a firm whack with a soft maul, preferring that it break off on land and not at sea. Each was good, as were the hoses and clamps. I likewise inspected the propeller shaft stuffing box, which is of the traditional type but which polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) packing has made dripless, and the rudder shaft packing gland. All good.

I made sure the lazarette and cockpit locker had good gasketing, and went so far as to ask Ellen to lock me in, to see if daylight penetrated.

I read that many yachts arrive in Europe with engines inoperative because of seawater in the fuel or in the cylinders, so I put a fresh greased O ring on the deck fill, and relocated the tank vent to a coaming pocket inside the cockpit. The vent had been on the outboard side of the coaming, where at sea it was often awash, and I am convinced moving it inboard was important. I also added a transom flapper valve to the diesel exhaust.

Two years earlier I’d completely overhauled the opening ports, with new glass properly bedded, and new gaskets. Now, I rebedded the staysail track and some other hardware, hoping to avoid all deck leaks. I regret not having sealed the boat, placing a window fan in the salon hatch on exhaust, and with a candle checked below for air leaks, a technique that might have revealed a small but inconvenient deck leak which appeared at sea.

Steering

I overhauled the Edson steering gear, replaced the wheel shaft bearings and inspected and lubricated the chain, cable, sheaves, quadrant and chassis. I had previously replaced a worn sheave, and replaced the original bronze sheave pins with stainless; Edson deems this essential. With the wheel locked I wrenched hard on the rudder to determine the amount of bearing play and to test the rudder’s internal structure. Our Hydrovane provides us with a spare rudder, but my work gave me full confidence in the yacht’s steering gear.

Navigation and weather routing

I wanted Far and Away set up so that, if we lost our engine and hence most electricity, we could proceed safely and in something resembling comfort. As a backup to the plotter I ordered Imray paper charts for western and southern Ireland. I carried two battery GPS devices, one in the ditch bag and another in a Faraday bag, where it might be protected from a lightning strike. I provided candle lanterns, and have always carried a kit by which I can jump the propane solenoid.

We considered and rejected installing an Iridium system, but I wanted weather routing. Our solution was a Garmin InReach Mini, with its global texting ability, combined with PredictWind which my wife would use at home. During the winter evenings Ellen practiced with PredictWind and the InReach. We became confident that, if our communications worked, once or twice each day she could recommend useful courses and give us a heads up as to the forecast. We retained Locus Weather for a departure window, and asked Locus to be available if Ellen was puzzled, or alarmed, by the routes PredictWind suggested.

The Accommodation

It’s not an unusual story – many yachts have been knocked down and badly damaged, and on top of trying to keep the boat afloat there’s the immediate need to doctor a crewmember lacerated (or worse) by flying gear. So I made sure Far and Away’s batteries were immoveable, and likewise secured the cabin sole hatches, using a bungee stretched across the opening that could be attached to a hook on the panel’s underside. I likewise double secured our new 10-pound fire extinguisher, with a cable tie attached to the bulkhead by a screw small enough to rip out if one yanked on the extinguisher.

Eric Hiscock emphasizes that an oceangoing yacht’s accommodation must be as nearly serene as possible. Crockery, glassware and bottles banging around, wind whistling through a hatch, annoying drips, even swinging oil lamps, are best avoided, as is sunlight streaming through a port and interfering with sleep. I focused on this both before and during the voyage. It’s the responsibility of the person on watch to quiet the cabin when crew are trying to rest.

Final preparations

Investigating insurance for the voyage, I was told “You’re too small.” Our existing policy would cover us until we were off soundings, and I could self-insure for the voyage, but I wanted hull and liability coverage in place the moment we reached Irish waters. This was easily obtained, at a reasonable price.

Launch day came in early June, 10 days before we hoped to depart. I paid special attention to rig tuning and followed Selden Mast’s advice to really tighten down the rig — no slack in the leeward shrouds until 20 degrees of heel. This reduces dynamic loading imposed by the mast being allowed to move.

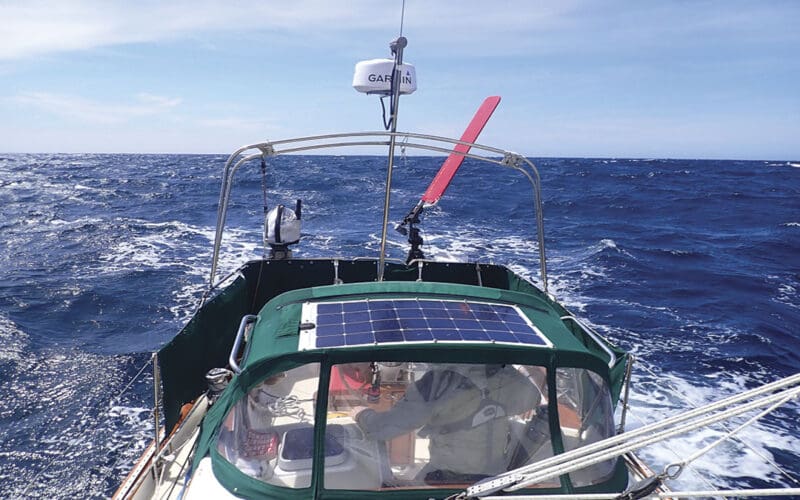

We rigged the weather cloths, using cotton string so a boarding sea would break the lashings and not the stanchions. I’d ordered two additional weather cloths for the stern pulpit, so the cockpit was fully enclosed. We kept the dodger, with its 130-watt solar panel, but stowed the bimini and its panel. We removed the 20-kilo Vulcan anchor from the sprit and stowed it in the bottom of the cockpit locker, lashed to padeyes screwed to shaped oak pads epoxied to the hull. I dropped the chain into the locker, first marking its end with survey tape, and carefully plugged the pipe with a greased rag and a plywood cover.

We carried 40 gallons of diesel in the tank, plus two five-gallon jerry cans lashed to the after rail. Our only gasoline was in the outboard’s integral tank. Forward of the cockpit nothing was stowed on deck except the dinghy, just forward of the hatch garage, deflated, tightly bagged and lashed to Harken folding padeyes. That’s as it should be.

The life raft lived in the cockpit well, where it was protected and at hand. The survival suits were in the top of the lazarette, equally close. The ditch bag, containing the EPIRB, handheld ICOM radio (with AIS!) and a Spot satellite device, was in a backpack near the companionway. I’d strap that on if we had to abandon.

The voyage

Despite my pre-voyage jitters (I told my brother “I feel like I’m jumping off a cliff”, and he said “You are!”), the preparation paid off in a swift, drama-free passage, 22-days at sea, with an average noon run of 139 miles, excellent for a heavy yacht with a load waterline of 27 feet. A few days after an overnight shakedown to Martha’s Vineyard, Locus Weather said “Go” and we motored out of Menemsha. Following Jimmy Cornell’s advice in World Cruising Routes, we headed south to about 40 degrees north, before steering due east, hoping to pick up the Gulf Stream for a few days before coming left for Ireland. This route avoids the calms found further south, for example by a yacht planning to stop in Bermuda, and increases the probability of the yacht enjoying robust fair winds from lows passing to its north. At the same time it avoids the cold fog and heavier weather associated with the more northerly great circle route, which transits the Grand Banks.

As it happened, we had the Gulf Stream for less than two days. We reached the Locus waypoint, encountered 76 degree F water (24 C), warm air and two knots of fair current, and had a 180-mile noon run that day. But the next day I came up for my watch and found both air and water chilly, and the fair current gone. Ellen (who was back in Maine and acting as our communications contact) got in touch with Locus and Ken McKinley suggested we waste no more time looking for the Gulf Stream, a surprisingly skinny thread in that longitude, and we steered northeast.

The PredictWind/Garmin InReach system worked beautifully, giving us excellent routing at a modest price, and as a bonus allowing my wife to play an integral part in the voyage. The InReach used almost no power, received and transmitted reliably from below deck, and even left a breadcrumb trail all the way across.

Day after day we had strong westerlies, often 20 to 35 knots, with infrequent light winds. The log shows a single day of winds forward of the beam. Late in the voyage we saw winds in the low 40s, but still from the right direction. Visibility was excellent and it was fairly warm, too – air and water temperature in the mid- to low-60s (15 to 19 C).

We stood three-hour watches from 1800 to 0600. At our latitude the June nights were pleasantly brief. During the day we did not have a formal watch schedule, and typically the person on the dawn watch let the other sleep in. We both got solid naps during the day and neither of us became exhausted.

We typically flew a single- or double-reefed main and the poled-out yankee, rolled out a little or a lot, depending. In strong winds a bit of yankee helped balance the boat, reducing the load on the Hydrovane and adding speed. If the yankee was fully rolled, but we didn’t want to go forward in boisterous conditions, we kept the pole up, perhaps until a watch change. Chafe at the clew was not an issue.

Jibing and mainsail control was easy, thanks to our twin boom tackle system, about which I have written in these pages before. I have a traditional boom preventer rigged but did not use it.

Carly, our Hydrovane, steered day after day in all conditions, and I never worried about an unintended jibe or broach. I kept a careful eye on the foundation bolts, just four of which take the strain of steering a 17,000-pound yacht, but the installation is rock solid and no play occurred. And I was happy to be able to lock the wheel, avoiding entirely the considerable wear a transatlantic passage imposes on a pedestal steering system.

For several days we had big seas, 18 or 20 feet I believe, when, late in the voyage, swells from a powerful low centered to our north combined with the fully developed sea from the gale we found ourselves in. That was exciting and a bit scary, but short of alarming. Three times the cockpit flooded, not because we were pooped as such but simply from a tumbling crest probably combined with a deep roll. The weather cloths helped, of course. We took no water below, thanks to our gasketed and pinned hatch boards.

The only gear failure we had was a chafed-through main slide (bronze – the Delrin slides showed no chafe). The engine ran well, and no water appeared in the Racor fuel filter, or in the fuel tank when I later sounded it using a dowel smeared with water detecting paste.

In short, the passage was a pleasure, including a truly gigantic whale close aboard, the occasional ship for company, a fat blackfin tuna boated and devoured, each watch and each day passing quickly until, one windy dawn, Mizen Head appeared. Incredibly, we had crossed the Atlantic.

Yet it’s not quite accurate to say the voyage was without drama. Seven days into the passage I became aware we were approaching the Titanic wreck site. I asked Ellen for the wreck’s coordinates as well as for an ice report. Then she texted that there had been a disaster at the Titanic wreck and a submersible was missing. Soon we began to hear radio chatter, including the words “hull banging” and “What’s the submersible’s call sign?”

Around midnight we passed three miles south of what was still a rescue effort, with seven ships on AIS clustered around the waypoint I’d placed for the wreck. We contacted the on-scene commander, advised that we were the sailboat just to their south, and asked if there was anything they needed, or that we could do. The answer was negative, we wished them well, and Far and Away pressed on for Ireland. n

Nico Walsh, a former Coast Guard officer, is an admiralty attorney living in Freeport, Maine.