Voyage planning and prepping starts with choosing your schedule based on weather, desired route, and many other considerations that require both online and offline information resources. In addition, a critical planning component is deciding what spare parts and supplies you will need, based on your boat’s characteristics, the length of your voyage, and its destinations.

Obviously, the first consideration that will determine all else is where you want to go. For most of us that is the easy part of the process. We have been dreaming about the big trip for years and imagining what it will be like. But you can’t just cast off the mooring lines and set sail when you feel like it. Major considerations, aside from any land commitments you may have, include the best season for a voyage, what weather is likely to be encountered in that season, what a general schedule will look like, and what food, supplies, and spares will be needed to make for a pleasant voyage.

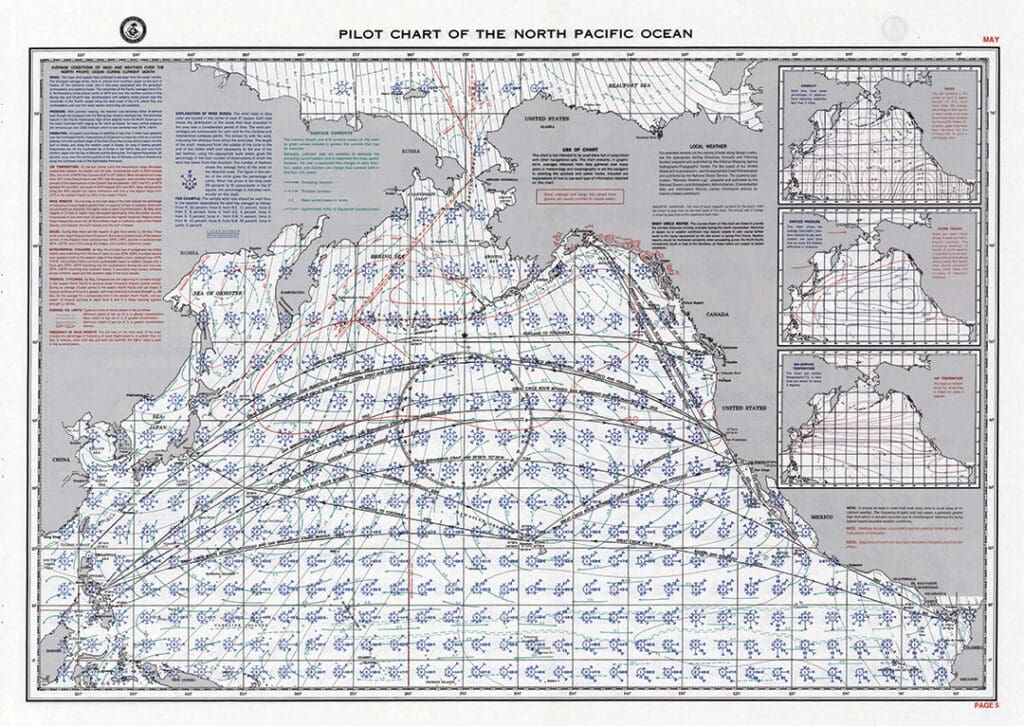

In the recent past many voyages were planned on the dining room table with a set of paper pilot charts, and these are still very useful tools to get an astronaut’s view of what winds, currents, and distances you will be dealing with. Like many other marine navigation products, you can still access these wonderful resources online via a government website (msi.nga.mil/Publications/APC) or from private websites like BlueSeas (offshoreblue.com), which is also a wonderful resource for cruising information on marine communications, cruising, navigation, safety at sea, and marine weather. You can download seasonal pilot charts for the world’s oceans, and there are links to printed portfolios of charts for purchase.

The bibles

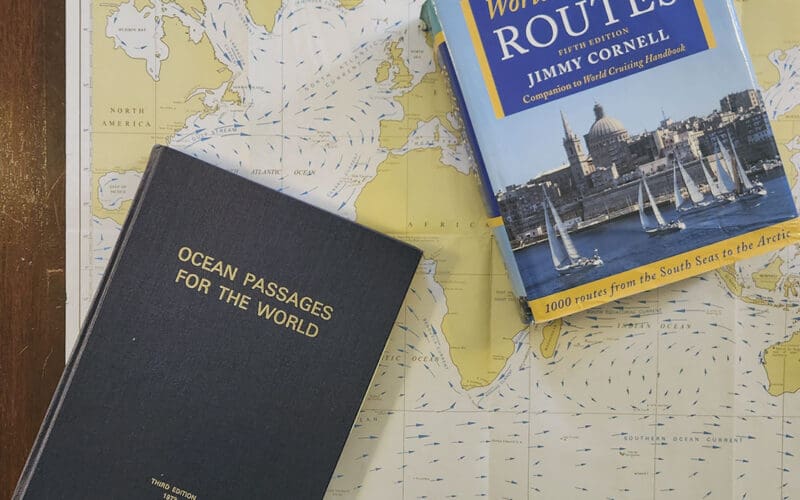

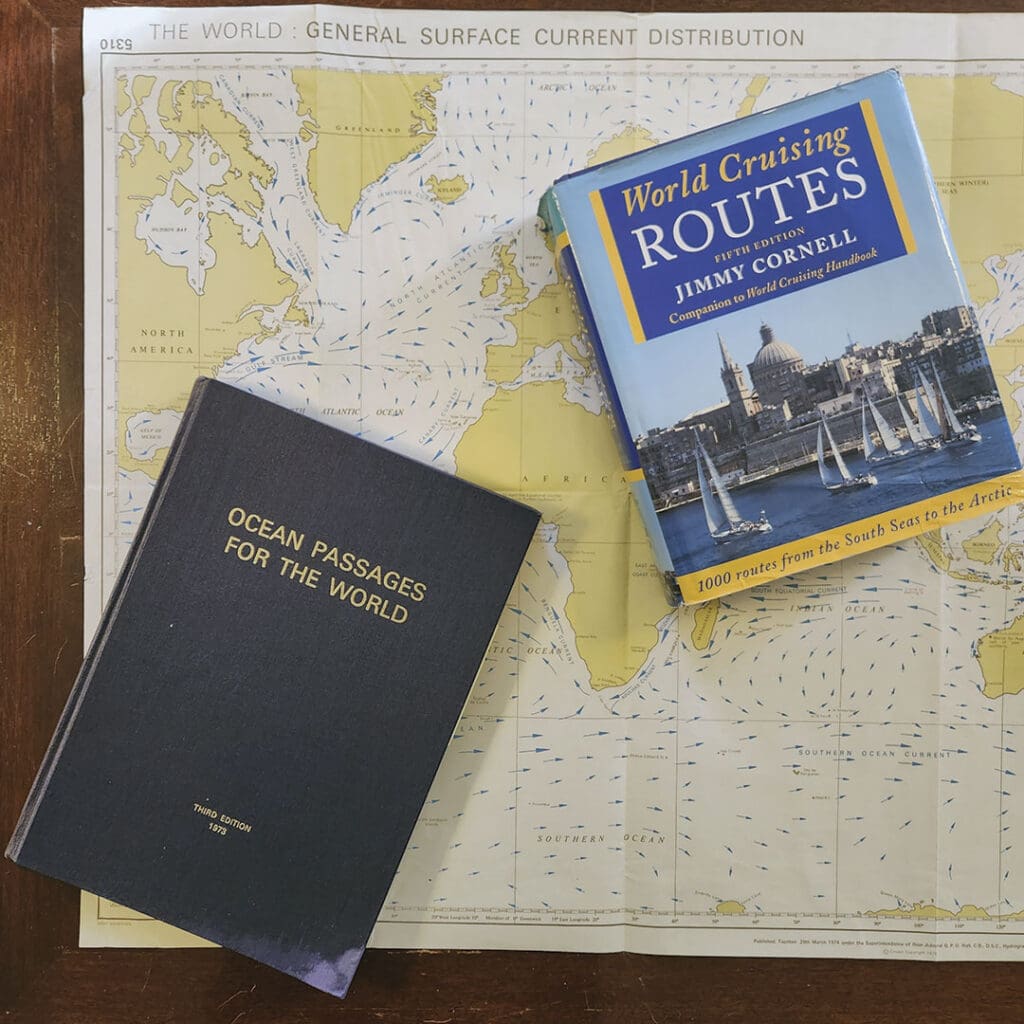

In the past, many of us purchased the official British Admiralty publication called Ocean Passages for the World, and this venerable tome is still available (for a big price) from Bluewater Books & Charts (bluewaterweb.com) and Landfall Navigation (landfallnavigation.com).

Ocean Passages was always more oriented towards commercial shipping, and is no longer the bible for cruisers. Instead, almost every voyage dreamer at some point latches onto a copy of Jimmy Cornell’s classic, World Cruising Routes, now in its 8th edition and available direct from the author (cornellsailing.com). Cornell’s book was written by a voyaging sailor for other voyaging sailors, and provides vital planning information on a huge number of possible passage routes for all the major cruising destinations in the world. Entries include distances, alternate routes, best seasons, information on currents and weather, and much more. And, now you can even download an e-book edition, meaning your boat won’t heel towards the side you put it on the bookshelf.

Go when the going is good

Between the pilot charts and Cornell’s book you will be able to determine the best time of year, best routes, and expected distances that will establish the outlines of your voyage. In today’s world of instant everything online we have become accustomed to picking up our phones to determine if we’ll need a raincoat within the next hour, and there are many online marine weather resources that can give us similar outlooks for the wind, currents, and offshore weather. Once you have established the best seasons for your trip, these weather resources can be very useful for pinpointing your actual departure date. But you can’t just look at the app on your phone and head out across the ocean if you haven’t put in the time and done the planning for the best seasonal weather patterns.

Avoid the temptation to ignore the voyaging wisdom, as presented on the pilot charts and in books like Cornell’s, gathered over hundreds of years. Online cruising forums are full of people asking for advice on going somewhere in the wrong season, often on a tight schedule, and often not fully understanding the conditions they will face. For example, you might be in New England in July and see what looks like a great stretch of weather on your phone app. Why not head off to Bermuda? If you’ve been doing your research you’ll know it’s hurricane season, and many storms pass close to or over Bermuda, or pass between Bermuda and the U.S. coast.

Similarly, a nice stretch of weather in November or December might be tempting for a quick run to the Caribbean, but a closer reading of the guides will let you know that winter cold fronts will sweep off the U.S. East Coast quickly and can often lead to gale conditions offshore. We were caught in such a front in early November heading out from North Carolina with a great forecast that turned into the worst offshore gale I’ve ever experienced. We lost our steering and rode to a parachute sea anchor for 24 hours with seas sweeping across the boat.

On the other hand, I have spoken to several circumnavigators who went in the right seasons on the right routes, based on the bibles mentioned above, and ended up never seeing much in the way of bad weather. A couple reported to me they never encountered a storm offshore in years of voyaging, and the worst weather they saw the entire time was on their return to Massachusetts.

For more on weather apps and other sources of information for making that final go-no-go decision, check out my recent article (oceannavigator.com/article/juggling-all-the-variables/).

Well laid plans

Assuming you have identified the best time of year for your trip, you’ll want to do some general route planning before taking off. Make sure you have all the paper and digital charts you will need, and be prepared with information on alternate destinations. Today’s charting devices and software, such as Navionics Boating App (navionics.com), allow you to easily carry not only the charts you plan on using, but the ones you might need if there is a change of plans. Similarly, a program like OpenCPN (opencpn.org) lets you tap into a vast collection of free and crowdsourced navigation charts for all over the world. I downloaded every U.S. NOAA raster chart for free and can use them on my laptop and Android phone using OpenCPN.

Another great planning tool is the Navionics online Chart Viewer (navionics.com). This free, web-based viewer covers the world and allows you to browse to any dream destination. I frequently consult the Chart Viewer even if I have the charts for the area on my laptop, phone, or onboard chart plotter. It is tremendously helpful to get a bird’s-eye-view of where you will be cruising before you get there.

In addition, I like to always carry some paper charts for any route. It is very easy to develop tunnel vision when staring at the small screen of your chart plotter on a laptop or phone, while the paper chart can be opened up to give you an overview of a large area yet with good detail. When offshore I like to plot my position on the paper chart several times a day just in case the electronics go down, and it serves to warn me ahead of time for things beyond the level of zoom on my screen, like shipping lanes, headlands, offshore obstructions like oil towers, etc. Paper charts are expensive to purchase new, but for offshore use it is perfectly acceptable to get old and used ones. I use some charts decades old, complete with my hand-drawn routes of previous voyages. Just be sure to not depend on these old charts for your final approaches to land. New charts can be ordered from numerous places, including Maptech (richardsonscharts.com), which is also a great source of cruising guides and chartbooks for U.S. and Bahamian waters.

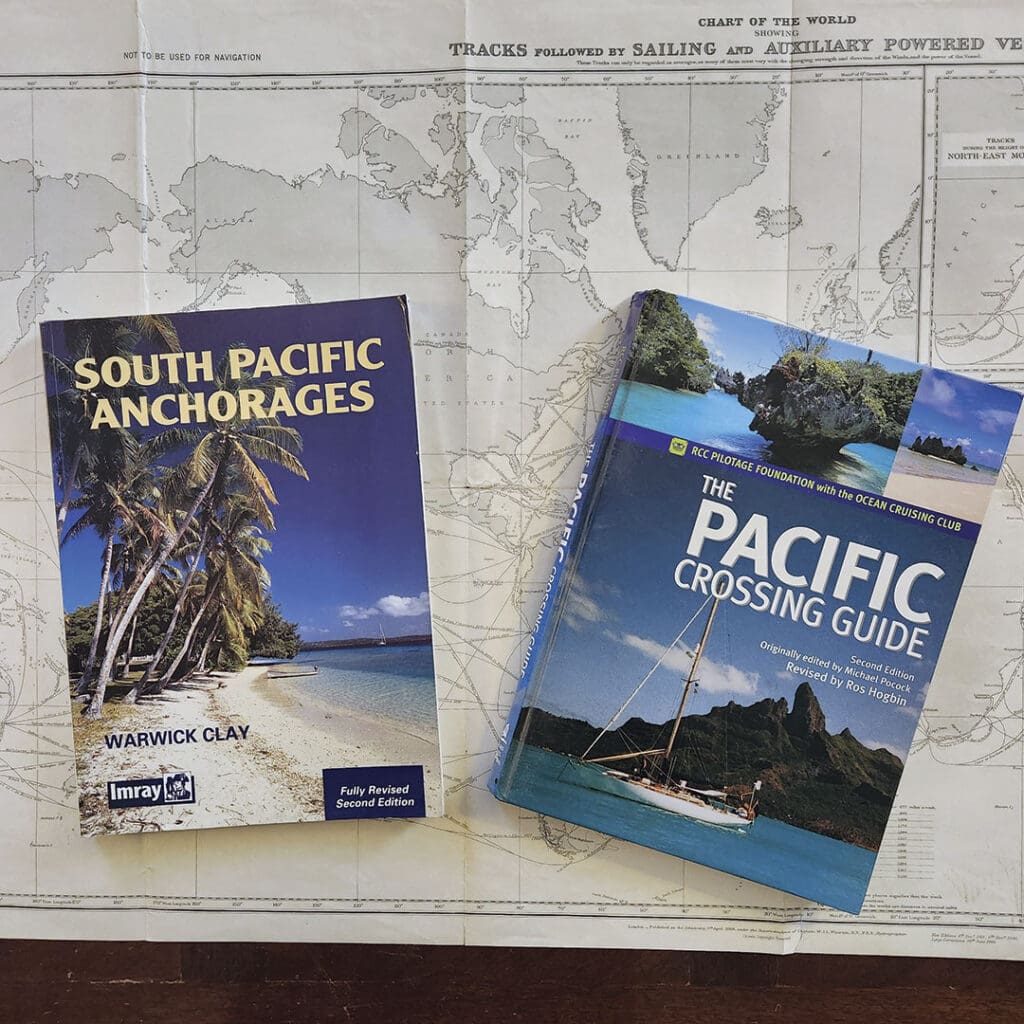

Cruising guides for wherever you are headed are invaluable. These are available at marine bookstores and online. Bluewater Books & Charts, Landfall Navigation, and Pilothouse (pilothousecharts.com), and The Nautical Mind (nauticalmind.com) are four of my favorites. Guides often contain very useful navigation information, including chartlets of harbors, where to anchor, how to clear customs, the availability of fuel and supplies, what to see and do ashore, etc. There are online resources for some areas that are really good, but I like to have the books onboard that will work without plugging in and even when wet.

Spare me!

Stocking up on navigation material is important, but so is establishing your lists and inventory of spare parts. A general rule of thumb we use when cruising long term is to plan on reaching a major restocking port about every three months. We’ve found that our heavy 38-footer can store enough non-perishables to last about three months. Consequently, that is my rough guide to what type and quantity of spares I need to carry onboard. Generally, if a place is big enough to have marinas, boat yards, big supermarkets, and other shopping, it is big enough to receive a shipment of important tools or parts.

There are two basic types of spare parts: must have, and nice-to-have. In the must-have category I put things like at least one backup GPS, whether handheld, a phone, a fixed mount, or whatever. Phones are surprisingly capable GPS navigation devices, and as mentioned earlier you can even use them as chartplotters. I find the GPS on my phone to be perfectly accurate, and I often resort to using it for the final approach to a harbor just because I can easily call up the local chart and view it anywhere onboard. Many phones are highly water resistant and quite durable too.

Similarly, I carry at least one portable VHF radio in addition to the fixed mount one. With a backup GPS, hopefully with backup charts on it too, and a radio you could navigate almost anywhere. Most boats will also have several portable compasses too, though you can actually steer a boat just by GPS if you need to. The radio is not absolutely needed day-to-day, but is critical in emergency situations.

Also in the must-have category are certain engine spares: belts, impellers, oil and fuel filters, engine oil, fuel treatments, repair items. In the repair items category I include things like all different sizes of hose clamps, sealants, exhaust wrap and repair tape, spare hose lengths, etc. My rule of thumb is to have the basic consumables to last a year of cruising, assuming no major breakdowns. Sailors are lucky in that we have a built-in backup system in case of engine failure, but power cruisers may want to carry an even greater range of spare parts and tools.

A friend of mine once pointed out that carrying spare engine parts just eliminates which part on the engine will break, and I have found this to be often the case! Luckily, I have found that major cruising rendezvous ports often have ways of getting stuff shipped in. Just ask around the harbor and someone will have already done this and will know the ropes. To facilitate this process it is important to carry the full engine manual onboard. Major engine and parts dealers and distributors are very experienced at sending parts anywhere, and they often can recommend a local supplier. Places like Trans Atlantic Diesels for Perkins (tadiesels.com), Hansen Marine Engineering for Westerbeke (hansenmarine.com), Oldport Marine Services for Yanmar (oldportmarine.com) and Beta Marine USA (betamarineusa.com) should be in your contact list, and you may want to order a master parts list for your engine.

I also bring several comprehensive boating equipment catalogs like the one from Hamilton Marine (hamiltonmarine.com). Needless to say, you can find anything online these days, but the printed catalog can be very helpful on a boat with limited Internet connections. Other great sources for a wide variety of marine gear include Fisheries Supply (fisheriessupply.com), Defender Industries (defender.com), Go2Marine (go2marine.com), and West Marine (westmarine.com).

You can’t have too many tools on a cruising boat. The right tool may be the difference between completing a repair or not. However, this is a vast subject on its own, and each cruiser will have to accumulate a tool set suiting their own skills, preferences, and storage space. Luckily, if you don’t have something onboard there is bound to be another boat in the anchorage that has it!

You can’t have too many flashlights! In addition, I have several headlamps, which allow me to use both hands while working on something. I’m trying now to standardize most flashlights onboard to use AA batteries, to simplify stocking things and to make them interchangeable when one fails. I routinely have at least three or four small flashlights at the nav station near the companionway, and I have several headlamps stored nearby. I also have a larger police-type light there for spotlighting things at night. In addition, there are flashlights near our bunks.

You can’t have too many flashlights! In addition, I have several headlamps, which allow me to use both hands while working on something. I’m trying now to standardize most flashlights onboard to use AA batteries, to simplify stocking things and to make them interchangeable when one fails. I routinely have at least three or four small flashlights at the nav station near the companionway, and I have several headlamps stored nearby. I also have a larger police-type light there for spotlighting things at night. In addition, there are flashlights near our bunks.

In the consumable category, I like to carry at least a year’s worth of items like electrical tape, small batteries, spare fuses, spare bulbs, distilled water for batteries, epoxy glue and resin, paints, caulking, zip ties, stainless steel wire, spare shackles, etc.

In the nice-to-have category I include things like underwater epoxy, a large bolt cutter that could cut my anchor chain or rigging, a torque wrench, electric drills and sanders for in port, a blow torch that uses disposable propane tanks, pipe wrenches for big stuff, spare wires and electrical cable, general electrical switch and connector spares, a soldering iron, a caulking gun, long tape measures for sails, chain, and rigging, etc. etc. A simple pair of battery jumper cables might be just the thing if you suffer an electrical breakdown and need to hook up a live battery to get your engine started in an emergency. I like to have onboard some long extension cords and a drop light for working in a marina or boatyard.

Where is it?

How do you keep track of all this stuff? Each person and boat will be different. I have stored things on my boat in the same places for so long that I have a pretty good idea what is where, but I also keep a written general layout of the boat’s lockers and contents. Some people will want to keep spreadsheets of where things are. I keep a running tally of repairs needed and supplies needed both on a notepad at the nav station and on my phone so I have the information when I am at the store. It is a good practice to make a note of any needed supplies as you use items up or complete a job. Each major repair is noted in the logbook, and at that time I make note of specific sizes needed for that job: hose size, clamp size, filter number, etc.

It is best to keep like stuff together: tools with tools, electrical with electrical, paint with paint, caulking, hose clamps, tapes, etc. all in the same lockers. However, some things are best kept near where they will be needed. For example, many cruisers keep emergency hull plugs tied to the seacock they pertain to. I keep a plastic jug of distilled water right in the battery compartment, along with spare big fuses for the ones located there. I keep jugs of engine oil and coolant near the engine. At my nav station I keep several rolls of various tape that can be used for quick repairs on lots of stuff.

Don’t leave home without it

In today’s connected and online world it is easy to forget how independent one needs to be on a voyage to remote places where you might not have a cellphone signal or access to the internet. Sure, some boats do have satellite connections, but that doesn’t help if the nearest town for a delivery is 200 miles away.

Get your planning charts, books, cruising guides, tools, spares, and critical consumables before you set off to avoid disappointment later. A cruising boat is really a cargo ship with passengers! n

John Kettlewell has cruised the waters between Labrador and South America for more than 45 years.