Among the hazards for those living or working in immediate or near coastal areas is that of coastal flooding. Coastal flooding occurs when ocean water moves into coastal areas, and is fundamentally different from flooding due to heavy precipitation, sometimes termed fresh water flooding. Fresh water flooding can occur in any area, but is more likely in low lying areas and near rivers or streams, not necessarily near the coast.

There are two major factors to consider when assessing the risk of coastal flooding. The first is the state of the tide, and the second is the presence of strong winds from an onshore direction.

The tide is defined as the periodic rise and fall of the ocean due to the influence of gravity from the moon and the sun. Without going into all the details, these gravitational forces lead to a wave that translates around the major ocean basins in a counter-clockwise fashion in the northern hemisphere. Thus the times of high and low tide are not the same in all locations around the ocean basin. The moon, being much closer to the earth, is the dominant gravitational force controlling the tides. When the sun and moon are on the same side of the earth, or on opposite sides, their gravitational forces are aligned and the sun’s extra input leads to a greater tidal range during these periods. This means that high tides are higher and low tides are lower around the time of the full moon and the new moon each month, and these are termed spring tides.

There are other factors which lead to difference the height of the tides, such as differences in the distance between the earth and the moon in its orbit, and to a lesser extent differences in distance between the sun and the earth. When the moon’s closest point to the earth in its orbit (its perigee) coincides with the full moon or the new moon, Perigean Spring Tides result, and these tend to be among the highest tides of the year. Because of other factors, these Perigean Spring Tides are not all the same height, and when considering these other factors, the highest tides of the year are colloquially termed “King Tides”.

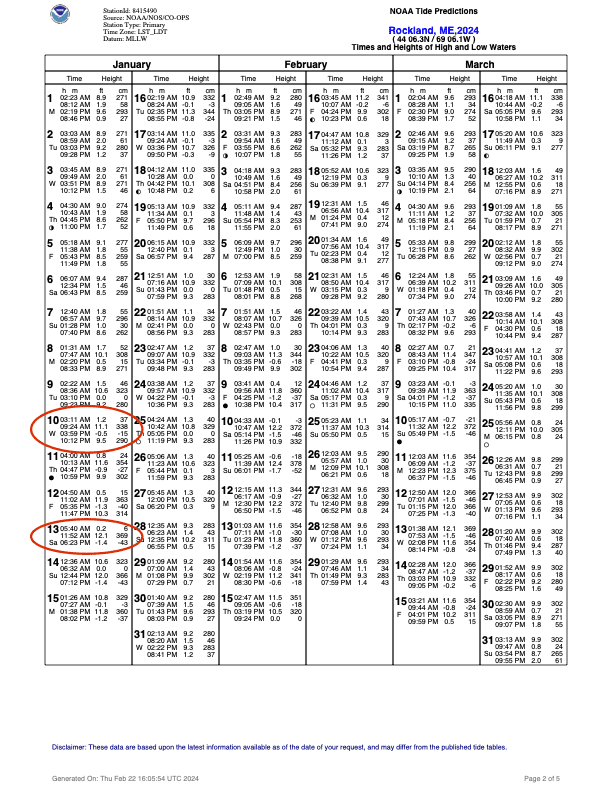

All of the gravitational factors controlling the tide are able to be calculated, and thus the tides are quite predictable. Tables showing the times of high and low tide and the height of the tide at those times are widely available, including on the NOAA website: https://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov.

Minor coastal flooding can occur in some areas around the time of high tide during a some Perigean Spring Tides and also during King Tide periods, but in most cases this type of flooding, while a nuisance, does not lead to major impacts.

The presence of strong onshore winds is a significant contributing factor to more serious episodes of coastal flooding. The force of the wind on the surface of the ocean will result in surface water being pushed in the direction of the wind, and when the wind is blowing onshore (toward the coast) this water will be driven in that direction which will lead to higher water levels. The amount of the water rise will depend on several factors, including the shape of the coastline, the nature of the undersea terrain, the strength and duration of the wind, and the distance (fetch) over which the wind is blowing. This phenomena is known as storm surge, defined as an abnormal rise of water generated by a storm, over and above the predicted astronomical (gravitational) tides. Because of the many factors which contribute to a storm surge, it is difficult to predict with precision, though great strides have been made in recent years.

Storm surge is often associated with tropical cyclones, and in fact can lead to the most significant damage associated with these systems. But strong non-tropical systems can also produce a storm surge capable of producing great damage. When a storm surge coincides with high tide, a storm tide results, and it is this situation which leads to the greatest damage, particularly if the high tide is a spring tide.

In January of 2024, there were two storms within a few days of each other which produced strong onshore winds for the northeastern U.S. which coincided with higher than normal tides. Both of these systems produced catastrophic flooding particularly along the coast of Maine where the timing of the strong winds and the high tides was aligned almost perfectly.

Figure 1 is the surface analysis from 0000 UTC 10 January 2024 (7PM EST 9 January) and shows a strong low centered over southeastern Michigan with an occluded front extending south-southeast to southwestern Pennsylvania. From there, a warm front extended east to the south of New England, and a cold front extended south through the Carolinas. The isobars around this low suggested that very strong winds from a general southerly direction prevailed over the mid-Atlantic coastal waters of the eastern U.S. In fact, storm force winds (48-63 knots) are indicated on the chart. This likely led to some storm surge flooding on the south shore of Long Island, New York at this time.

Figure 2 is the surface analysis 12 hours later at 1200 UTC 10 January 2024 (7AM EST). By that time the low had redeveloped where the three fronts met, and was centered over southern New Hampshire. As this system pushed up against strong high pressure to the east, the pressure gradient became more intense, indicated by the close spacing of the isobars. Also of note on the chart, a hurricane force warning was indicated, meaning sustained winds of 64 knots or more were present in this area. The wind direction as indicated by the isobars over the Gulf of Maine was SSE, or just about directly onshore for the coast of Maine.

Figure 3 is one page of the NOAA Tide Predictions for Rockland, Maine, in Penobscot Bay. On January 10, the predicted time of high tide was 9:24 AM with the height of tide at 11.1 feet above mean lower low water (MLLW). Examining the height of high tides through all of this chart reveals that this tide was one of the higher tides anticipated. The time of high tide coincided with the strongest onshore winds as shown in Figure 2, and the result was water levels 3 or 4 feet above what would have been expected if there had not been any onshore wind. In fact, for several locations along the Maine coast, water levels from this event broke records which had been set during the famous Blizzard of 1978.

Another factor to consider during coastal flooding episodes like this one is that not only will the water levels be higher, but there will also often be large waves generated by the wind. The combination of ocean water moving into areas which it does not normally reach and the large and battering waves led to damage in this event which will be counted in many millions of dollars. In addition to many waterfront business (boat yards, restaurants, etc.) which sustained serious flooding and damage to infrastructure, there were many piers which were ripped from their moorings, and several historic Maine lighthouses were damaged. These included The Rockland Breakwater Lighthouse, Pemaquid Point Lighthouse, and Marshall Point Light at Port Clyde, made famous in the movie “Forrest Gump”. Figure 4 is a photo of the Camden (Maine) Yacht Club, which is located just a few miles north of Rockland on Penobscot Bay, near the time of high tide on January 10, 2024. In addition to the obvious situation of waves breaking against the side of the building, note the huge wave breaking against the sea wall at the far right of the image in the background.

Amazingly, just three days later, another severe coastal flooding event impacted the same areas. The winds from the system on January 13, 2024 were not as strong, but the tides were higher, as can be seen in Figure 3. This meant that the flooding levels were about the same as in the January 10 event, but the waves were not quite as high, which limited the damage due to wave action.