There are few things a sailor fears more than a collision at sea. On our circumnavigation, unfortunately, it happened. Our random moment was an experience that will stay with us forever and it even resulted in some persistent PTSD symptoms for several years afterward. Luckily, we were able to extricate ourselves without losing our boat.

We had arrived back aboard our Montevideo 43 Bahati just before Christmas. I’d been on a job in Tokyo and my wife Betsy flew in to meet me in Japan for a short side trip to Kyoto before returning to Malaysia with the aim of sailing north to Thailand for Christmas with our friends aboard the cruising boat Empire, who were relaxing in Ao Chalong, Phuket, waiting to ring in the New Year. We had become good friends with Eivind and Heidi and their two young boys, Marius and Eirik, since our first meeting in the Galapagos and we felt like they were the closest thing to family we had among the cruising community. Marius and Eirik were like grandchildren in our hearts and minds. Nothing sounded sweeter than the idea of being with them to celebrate the holidays.

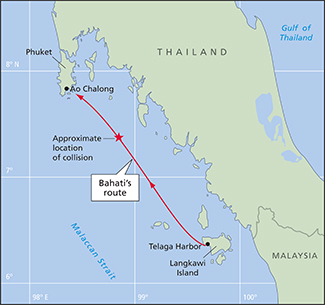

We provisioned and prepared to leave our good friends at the Telaga Harbour marina on the northwestern end of Langkawi Island on Christmas Eve, estimating that with the prevailing breeze behind us it would be an easy overnight sail north to Thailand. Betsy had come down with a bronchial infection in Japan and I was exhausted from a week of back-to-back corporate training programs, but we were determined to leave despite our collective fatigue. This was our first mistake. In fact, after discussing our itinerary we made the decision to sleep for six hours before casting off because we both recognized we weren’t really rested enough to put to sea. In retrospect, we shouldn’t have left at all, but, as the saying goes, “hindsight is 20-20.”

Quietly leaving harbor

We dropped the mooring lines and pulled in the bumpers around midnight, sneaking quietly out of the harbor under a gorgeous waxing moon. The prevailing night breeze from the northeast had filled in nicely and before long we’d hoisted all sail and cut the engine. Betsy went to her bunk and I settled in for what looked and felt like the best night’s sailing we’d had in recent memory. And it was Christmas Eve!

|

|

Bahati at anchor in Langkawi fjord just prior to the accident. |

For the first 20 of the 155-nm sail, we dodged numerous Malay and then Thai fishing vessels and traps, some of which were lit and some not. Even when things were lit they were done so haphazardly. As in most Asian countries, there is no rhyme or reason to nautical lighting schemes. If lights are placed on floating objects, they seem more for decoration than navigation. The trick is to keep your eyes peeled and do the best you can to avoid getting too close to whatever lies in your path. I dodged at least 50 obstacles during our first few hours at sea that night. Fortunately, the visibility was perfect. I could easily see to the horizon and there was no bad weather forecast for days to come.

Bahati was sailing along at a good 6 to 7 knots through the water and a little better than that over the ground with a favorable current pushing us gently from astern. We hoisted the entire mainsail and rolled out the whole yankee jib because the breeze was steady at 12 to 15 knots and not predicted to change all night. I sat at the helm, standing up and visually scanning the horizon 360 degrees every few minutes and then checking the radar every 15 minutes or so. We do not like to run the radar constantly — unless conditions warrant it — because it sucks up so much power. Again, in retrospect, we should have left the radar running with the alarm set. I was used to sailing alone, however, and feeling cocky that night after weeks of single-handing on the run up from Singapore to Langkawi. I trusted my eyes and ears more than was prudent.

Around 3 a.m. I began feeling quite sleepy. I knew it was time to wake Betsy for her watch but I could hear her coughing in the aft cabin and I decided I’d give her a break and just carry on. This was another bad mistake. I should have trusted my better judgment. She later asked, with a touch of anger in her voice, “Why didn’t you wake me?!” All I could say was that I felt sorry for her and wanted to help her feel better. Lousy excuse.

|

|

The relatively short passage had a major mishap. |

Again, I scanned the horizon a full 360 degrees a couple of times with my naked eye and I turned on the radar for one more check. I saw nothing for 12 miles ahead and when I jumped out to 20 on the scope, still no blips appeared. I set the alarm on my wrist watch for 20 minutes, again something I’d done frequently in recent weeks while solo sailing. At the rate of speed we were sailing, in that much time we would cover only 3 or 4 nm. I knew I could see that the coast was clear much farther ahead than that. I double-checked the electronic autopilot that I knew I could trust to sail a straighter course than the Monitor wind vane self-steering unit under these circumstances. I’d replaced the S2 steering arm on the auto-helm during the recent refit time in Singapore so I completely (or as completely as a sailor knows is honest) trusted the steering system. I placed my watch, with the alarm switched on, right next to my head and closed my eyes.

KABOOM!

I was rudely shocked awake by a horrific noise. My eyes popped open. Bright lights flashed everywhere. It seemed like broad daylight but I knew it couldn’t be. Was I dreaming? I struggled to my feet as the boat lurched rudely from side to side and fore to aft. The mainsail was still full and pulling hard but I could see the jib was luffing a bit and appeared to be loose on its halyard. Hanging on tightly and remembering the “one hand for yourself and one for the ship” rule, but neglecting to snap into the lifelines or the jack lines in my panic and haste, I rushed forward. As I ducked from under the dodger leaping out of the cockpit, I quickly saw that we’d collided at 90 degrees — “T-boned” a large, apparently Thai, fishing vessel. The fishing boat had gear hanging over the side that had become tangled with our rigging. The Thai boat appeared to be dead in the water. Only later did I realize that she was anchored and, in fact, tied aft in line with another boat about the same size and shape. We’d managed to nail TWO large fishing vessels out there in the middle of “nowhere.” And, since they appeared to be anchored, there was no possibility that one of them had run into us. No, in fact, we’ve sailed straight into the second boat in a line of two and our bow had lifted slightly over their high bulwark. If we’d been going any faster we might’ve leapt completely out of the water and landed on them.

Once I was able to process what had happened, I shouted for Betsy to get on deck. Suddenly I noticed that the jib roller furling gear was askew and, in fact, the whole foredeck had been peeled back like a sardine can. I shouted aft over the noise of waves, wind and crashing metal, “Better get a tarp from the lazarette. We got a hole to cover here and we’re taking on water!” I could see the waves jamming up between the two boats in the rough conditions, and washing over the hole in the bow, maybe filling the hull. Fortunately, the anchor locker, which was in the damaged area, is protected by a watertight bulkhead, which means there is little danger of sinking but in the panic of the moment I was not able to process that reality.

|

|

A Thai fishing boat similar to the vessel Bahati hit. |

Betsy stumbled on deck and I shouted to see if she’d been injured as I grabbed the orange tarp out of her hands and ran forward again. “Clip in!” she yelled at me after confirming that she had no serious injuries. I did clip in and silently chided myself for not doing so sooner. Good thing she was there to remind me, as always, though too often I resented it. Not that night.

I managed to cover the gaping hole in the bow with the tarp and set to work trying to lower the sails. That proved difficult, as they were both full of wind and pulling us ahead, jamming us harder against the heavy wooden fishing vessel and steadily increasing the damage.

As far as I could tell there was no serious structural damage done to the other boat. I turned to run back to the cockpit, consumed with the idea that I’d better get the engine started so we could try and extricate ourselves from the tangled mess of rigging and fishing gear. A couple of sleepy fishermen had stumbled on deck aboard the Thai vessel. They were standing near the rail, rubbing their eyes trying to figure out what the hell had happened and why this strange American apparition had run smack into the side of their home. I yelled, “I’m so sorry! Is everyone OK?!” Feeling like a fool, I realized they probably didn’t speak English so my shouting was in vain. They just stared at me, expressionless.

I got back to the cockpit and thrashed around trying to locate the key, which had fallen out into the cockpit on impact. I finally found it and got the engine started. I threw it into reverse, and gunned it, praying that there was nothing underneath our stern that might jam the propeller. We were able to back away from the Thai boat. Immediately the bow swung to leeward and we started sailing away. Luckily, the vessel we hit was not the one with the anchor down or we might simply have run straight into the second of the two sleeping hulls — or worse, run over the tow line in between them and snagged it in our prop. Instead, we found ourselves suddenly making distance away from them as I tried to bring Bahati into the wind so we could lower the sails.

|

|

Bahati post-collision with an orange tarp covering the damaged bow. |

Securing the mast

We managed to get the mainsail rolled up pretty quickly, but the jib roller furling gear was jammed. I looked aloft and realized with a shock that the mast was heaving slightly fore and aft. It came to me like a bullet to the brain that we might be at risk of losing our mast. The forestay onto which the luff of the yankee jib was fastened, and which is also the primary forward support for the mast, had been compromised. The foredeck had been lifted by about 2 feet vertically and the same distance toward the stern. That meant that the headstay was loose and the only thing keeping the mast from falling over backward was the small midstay, which was attached to the mast about three-quarters of the way up.

Realizing we’d be in for some real trouble if that stay popped under the strain, I ran forward again and quickly freed the two spinnaker halyards and the spare jib halyard clipping them onto cleats on the foredeck, and then tightened them down using the free mast winches. That seemed to straighten things out a bit and I was finally able to roll up the jib using a lot of muscle on the starboard cockpit winch. Once we had both sails furled and we knew the engine was running OK, we could relax a bit, aware that we were neither in danger of sinking, nor (we hoped) of losing our mast.

We looked back toward where the two fishing boats were anchored. They were nearly out of sight. For all the lights that were shining in our eyes, including our own deck lights and everything else they had burning, they did not stand out very brightly under the nearly full moon and bright starlit sky. Not that lights would’ve made much difference in that moment because we’d both been fast asleep, me at the wheel, Betsy snug in her aft cabin bunk.

|

|

Looking up at the bow after most of the damage had been cut away before rebuilding had begun. |

I later realized that, in fact, I must’ve slept through my watch alarm. I had been so tired that it took a real crash to wake me up and, even with that, as I got to my feet I was in a stupor.

Needless to say, we were both in shock. It was a hell of a Christmas present for us as well as for our unwitting Thai fishermen friends.

By the time we got underway again, dawn was breaking and we could see the southern shoreline of Ao Chalong. By mid-morning we were powering into the anchorage, looking for a spot to drop our hook for Christmas breakfast. Because of the damage done to Bahati’s bow there was no way we could use the anchor system, so we had to rig the spare hook and throw it off the stern. We looked an odd sight with our anchor rode streaming astern and a bright orange tarp covering the bow like some kind of bizarre Christmas package waiting to be opened.

Reporting the accident

After breakfast we launched the dinghy and ran ashore to report what had happened. I found the Port Captain’s office and presented our papers and passports so we could officially clear-in to Thailand. At the same time I described what had happened to us at sea earlier that morning. The kind lady behind the desk smiled at us and asked if we were OK. We told her we were, though our boat had been badly damaged. We also told her that as far as we knew no one on the fishing vessel had been injured and their damage appeared to be minimal. She laughed and said, without a moment’s hesitation, “Oh, they are probably already out there fishing again!” I asked her if anything had been reported by radio or phone and she said not that she was aware but she would let us know if she heard anything. I got the impression that she didn’t imagine she would.

She told us we should report the incident to the local police as well and then she mentioned something about possible illegal fishing and I realized that the boats we ran into might, in fact, have been Malay boats fishing out of their territory — another reason why they would probably not have reported the accident.

|

|

The newly rebuilt bow as seen from on deck. |

We stumbled back to the boat and fell into a deep and disturbed sleep, still trying to understand exactly what had happened. Upon waking with a start early in the afternoon, we remembered it was Christmas and we hung a few decorations including some plastic flowers we’d bought in Penang, which we draped off the bow. Their bright colors jived nicely with the orange tarp. We did not add any blinking lights to the mix.

Later on, we called our friends aboard Empire who were anchored around the corner in a big open bay called Nai Harn. They commiserated with us and suggested we take a taxi over to the beach near where they were anchored and celebrate Christmas with them. We took them up on their invitation instantly and immediately felt better knowing we were close to friends.

Within a week we’d located a boatyard further north that agreed to give us an estimate for damages and repairs. The final cost for the work fell short of our insurance deductible so we were out-of-pocket nearly $15,000 USD, but grateful nonetheless. It could have been a much bigger disaster. We never did hear anything from the police or the Port Captain or anyone else for that matter. Almost two months later we were ready to put to sea again — a lot poorer and a little wiser.

Nat Warren-White is a few years out from completing a five-year circumnavigation aboard his Montevideo 43, Bahati. On many of those miles he was accompanied on Bahati by family members, including his wife Betsy and son Josh. Accounts and pictures of the trip are at his blog at www.bahati.net. He is currently working as a management consultant while scheming his next voyage.