As wind speeds increase and the rail begins to dip, it’s time to think about reducing sail. With most modern jib furlers this task is pretty straightforward: You simply roll the sail in around a foil on the headstay. Mainsail reefing or furling on the other hand, has not been so simple. With more options and methods of reefing available, it can be important to pick the system that best fits your needs.

Reducing sail in a timely manner is important not only to the comfort of the crew but for the safety and efficiency of the vessel as well. A boat pushed too hard on her side will not only be uncomfortable but will also cause undue leeway and weather helm, reducing performance. Too much sail can also place higher loads on gear and equipment, as well as making the crew work harder. Pushing hard may be okay for a racing boat with a large crew, but for the average short-handed cruising boat it makes little sense.

|

|

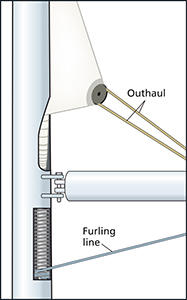

In-mast mainsail furling setup. |

The trick when reducing sail is not to reduce sail efficiency at the same time. Most sails are designed to be used fully set and will have ideal shape in that configuration. Once reefed, the shape changes and rarely for the better. This is why most racing boats will have a large set of sails for several wind speeds and conditions. A cruising boat, however, cannot carry a large selection of sails nor does it have the crew required for frequent sail changes. The compromise is being able to reef or shorten the sails already hoisted.

As any racing sailor will tell you, the real trick when reefing is maintaining a good sail shape for efficiency. This is particularly true with mainsails. Because jibs are attached on a single side, maintaining shape is a bit easier, but mainsails present a bit more of a challenge. Additionally, on a cruising boat reducing sail needs to be easy for a short-handed crew.

|

|

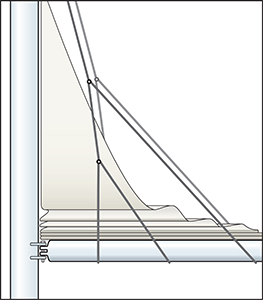

Note the vertical battens that allow sail to be rolled up from the luff. |

As with most things on boats, there is no simple answer to the problem of being able to easily reef a mainsail. There are several systems available; each has its own merits and drawbacks. Ease of use, sail shape and safety all play a part in selecting just what system is best for your boat, rig and type of sailing. The three primary types of mainsail reefing systems readily available for the average cruising boat are in-mast furling, slab or jiffy reefing, and boom roller reefing.

Of course, none of these systems is perfect, so let’s look at what each has to offer to help determine what might be best for you and your boat.

|

|

Furling line drives a screw actuator for spinning up the sail. |

In-mast furling

In-mast furling is rapidly becoming one of the more popular systems for the modern cruising boat. With this type of furling there is a foil inside the mast that the sail winds around just like a roller furling jib. A line is used to turn a drum to roll the sail in, while an outhaul is used to unfurl the sail. These systems have become popular on many production cruising boats. They are simple and reliable if used correctly. The sail can be reefed to any size and all the control lines can easily be run back to the cockpit so that you never have to go on deck to reef the sail. As most of these systems roll the sail up inside the mast, a sail cover is not needed. When done sailing, the sail is simply fully rolled into the mast where it is protected with only the clew remaining exposed to the weather.

The drawback to this type of mainsail furling is that it requires a purpose-built mast that is designed with room inside for the sail and furling gear. The extra weight of the larger mast section along with the sail can reduce stability somewhat if the boat was not designed for this. They can also be hard to service and there are a few cases of sails being stuck partly open. Newer systems and care when using make jamming unlikely but still possible. Perhaps the biggest drawback to in-mast furling is the loss of sail area and shape. Because battens cannot be used, the roach of the sail has to be neutral or straight; also, the sail must be cut fairly flat and without much draft so that it will smoothly roll into the mast. As sails are basically wings, good shape is important to efficiency — too flat and it will not provide good lift. Some sailmakers have used vertical battens with some success to overcome this, but it remains a problem.

|

|

A screw actuator. |

Another issue with in-mast furling is the possibility of the sail becoming jammed in the mast either partly or fully out. This can become a dangerous situation, but in my experience it is avoidable if care is used while rolling the sail in or out. In most cases the boat needs to be rounded up and headed into the wind while furling or unfurling the sail to avoid problems. Additionally, boom angle can affect how the sail operates when furling.

Slab reefing

The more traditional slab or jiffy reefing is an old standby that, like in-mast furling, has some pros and cons. Slab reefing is lowering the sail to a set of reef points or grommets in the sail and securing it off along the boom. The advantages to this system are that it maintains a good sail shape and allows the use of a fully battened main. It is fairly simple and all the gear is at deck level should something go wrong. It is inexpensive and easy to set up.

|

|

In a slab reefing setup, reefing lines run up to eyes in the leech of the sail. A corresponding eye is set into the luff at the same level. |

The disadvantage is that most setups require going on deck to reef the sail. Some systems do run lines aft to the cockpit, but this gets a bit tricky and can really clutter the cockpit up with lines. Unless the sail is fully battened, it can flog and flap in strong winds while lowering and securing, making this operation a bit more intense.

To gain better control of the sail while reefing, a few different systems can be deployed. Lazy jacks, which have been in use for many years, are a series of small lines that are attached to both the mast and boom on either side of the sail. These lines cradle and help control the sail as it is dropped, guiding it onto the boom as it is lowered. This system works pretty well, taking care to keep the battens from fouling on the lazy jack lines while raising and lowering the sail.

|

|

Lazy jacks are static lines that help corral the sail as it is lowered. The Dutchman lazy jack system uses lines running vertically that are woven through the sail. |

To get around the problem of the sail fouling in the lazy jack lines, a system called the Dutchman was developed. A Dutchman is like a lazy jack, but instead of lines on either side of the sail, a series of single lines are run from a topping lift through the sail to the boom to make it a bit like a window blind. The line is woven in and out of the sail so that the sail folds around the line as it is lowered. This eliminates the problem of the sail or battens fouling outside of the lines. This is a good alternative to the traditional lazy jack system, but it is not perfect. This system can be a bit finicky to operate and line tensions need to be kept tight so the sail will not bind when lowering. These lines can also chafe and wear on the sail.

As both lazy jacks and the Dutchman systems can make fitting a sail cover a bit of a challenge, Doyle Sails came up with the StackPack system where the lazy jacks and sail cover are built together. This system eliminates the need for a separate cover as it is now part of the system, permanently attached to the boom. The sail cover essentially becomes a big bag to catch the sail as it is lowered and this in turn helps keep it under control. The reefing lines are run through the StackPack for easy access. The disadvantage is that the StackPack can make it hard to access the foot of the sail and top of the boom inside the cover. This can make getting to fouled lines a bit of a challenge. I have also found on larger boats the top of the StackPack can be quite high up off the deck, requiring crew to climb the mast a short distance to help feed the sail into the cover should it foul. I have used some systems where you have to get up fairly high to push the sail into the StackPack. This, of course, can be a design problem with that particular installation, but does show what can go wrong. Having to climb up, even a short way, on the mast in bad weather can become a safety issue. With either plain lazy jacks or the StackPack, the lazy jack lines should also be pulled forward against the mast to prevent the sail battens from fouling when raising the sail.

|

|

A mainsail cover from North that stays on the boom and is designed for the main to be lowered into it. Note lazy jacks are part of the mainsail handling system. |

Boom furling

Finally there is in-boom roller reefing. First developed in the early 1960s, roller boom reefing lost favor due to its difficulty to use and poor sail set. I confess I am old enough to remember using one of these early systems and can say it was pretty awful. It required three crew to operate: one to lower the halyard, another to crank the boom around and yet another to pull the leech back on the boom as it was rolled up. The end result was a baggy sail with the aft end of the boom dropped down so as to sweep the deck clear of any unaware crew.

Times have changed and in-boom furling is having a resurgence, although in a modified form. Back in the day the whole boom rotated, but with today’s systems a separate mandrel inside a larger hollow boom is used to wrap the sail around. This allows the use of a fixed vang and other control lines, as well as protecting the sail so that a cover is not needed. These systems work well with the fully battened sails with a large roach popular on catamarans and other modern rigs. Unlike most in-mast furling systems, in-boom furling can be fitted to an existing rig, making this an interesting option for upgrades.

|

|

A Leisure Furl in-boom mainsail furling system. |

Leisure Furl has led the way in development of in-boom furling with a focus on larger boats due to the higher cost of these systems. These systems are slowly being tuned and perfected so that the cost is now down to where they are practical for mid-range boats. There is also more competition in this market from companies like Schaefer Marine and Profurl as the systems gain more acceptance.

Today’s systems are easier to operate and provide a much better sail shape. A few advantages of this system over in-mast furling are keeping weight lower, ease of access for service and troubleshooting, and the ability to use a fully battened sail with a large roach. Due to a better sail shape, these systems are even gaining some foothold with racing sailors.

|

|

The boom is set up with a wide slot that can accept the bulk of the fully furled sail. |

Keep in mind nothing is perfect and in-boom furling is not without its problems. These systems are not cheap and the cost to retrofit a boat can be high. Like any other mechanical systems, in-boom furling is subject to failures and jams. Most of these systems require a trip on deck to operate as well. Like in-mast furling, in-boom works best if the sail is designed for this use; so, if retrofitting a boat, it is best if a new sail is purchased with the system, adding to cost.

Before deciding on what systems will work best for your individual needs, it helps to understand how each works and what tradeoffs will have to be made. For ease of use on a short-handed cruising boat, the in-mast systems are a good option. For those a bit more performance-orientated, in-boom furling could provide a good solution, and for those that like to keep things simple while getting the best performance, slab or jiffy reefing may fit the bill. Each has pros and cons, but like most things on a boat, each will appeal to a different type of sailor. If unsure of what system might be best for your needs, try talking to and perhaps sailing with others who have different systems, then decide what best suits your needs.

Contributing editor Wayne Canning is a writer, photographer and marine surveyor.