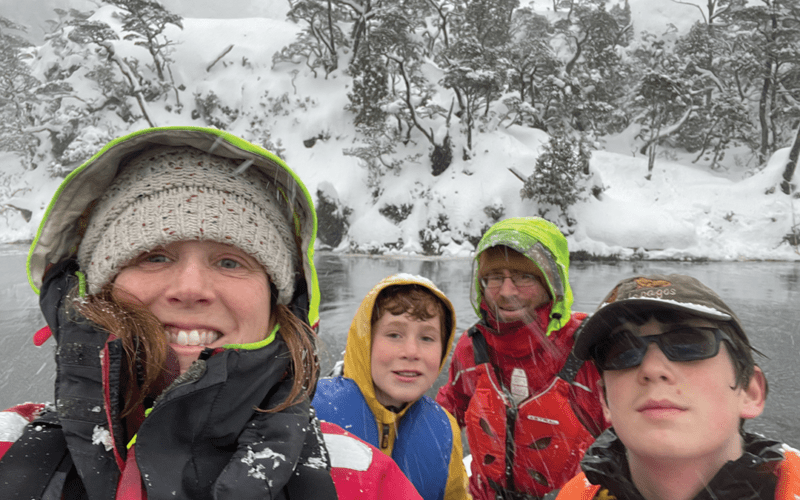

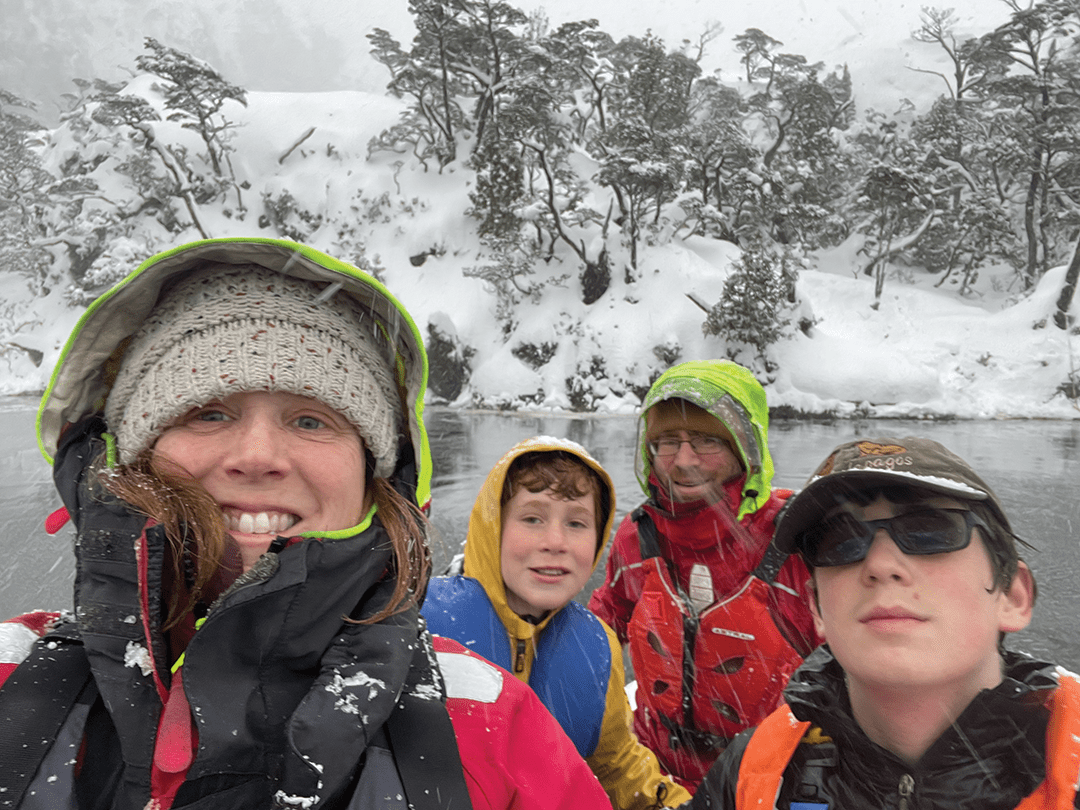

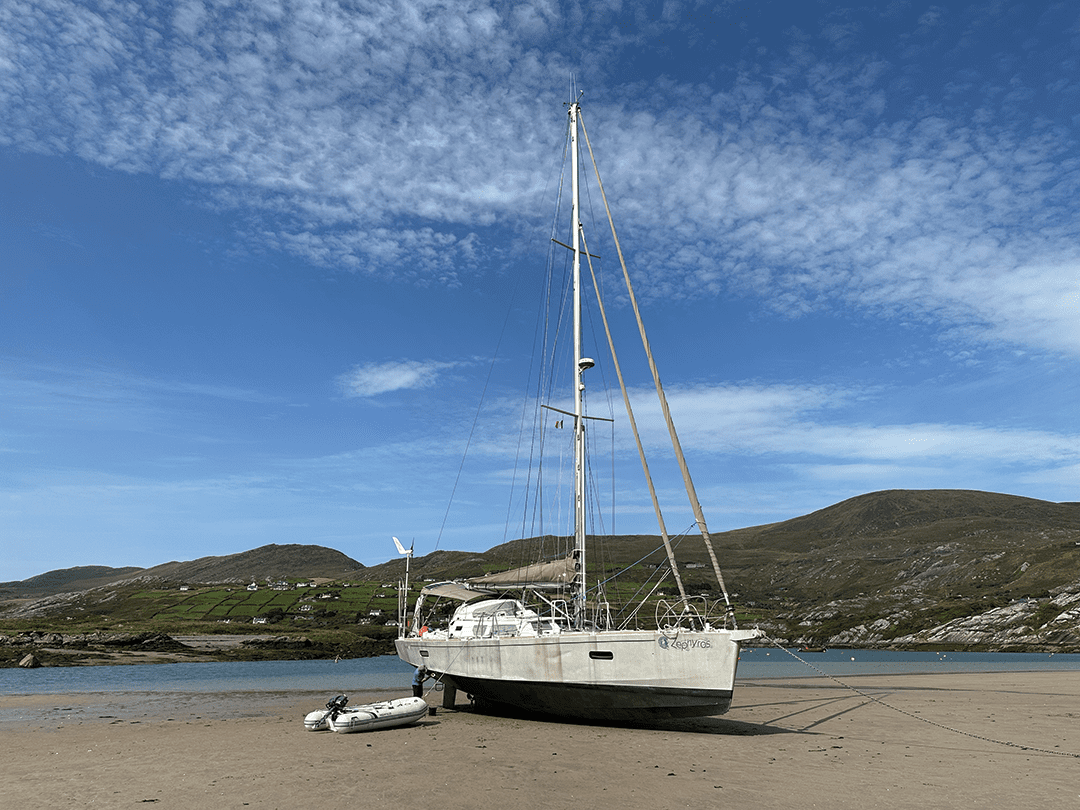

Jon and Megan Schwartz, along with their sons, Ronan, 16, and Daxton, 14, have been cruising full time aboard their Boreal 47, Zephyros, an aluminum expedition monohull, since 2017. Since picking up the boat at the factory in northern France, they have sailed 40,000 NM together. Driven by a desire to explore the world and experience its disappearing wilds, they have often pursued places less traveled. They started in northern France, the UK, Atlantic Spain and Portugal before heading into the Mediterranean for a season.

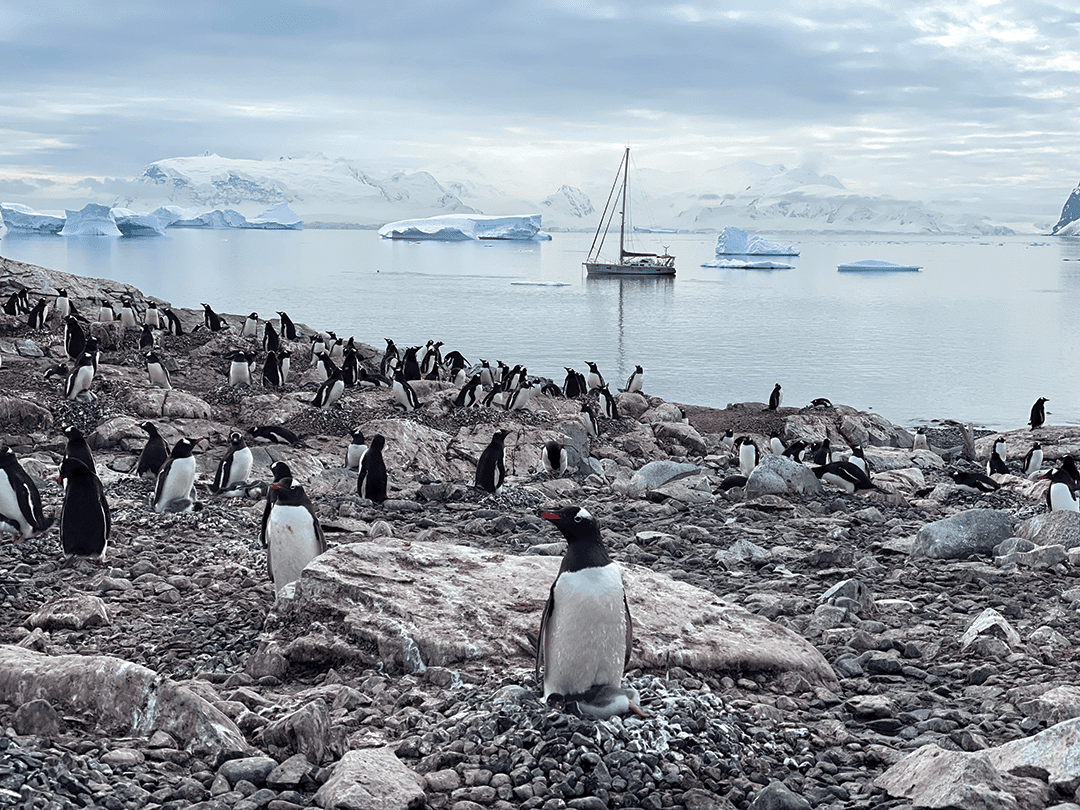

The Paxtons then crossed the Atlantic Ocean from late 2018 to early 2019. They were awarded the 2022 Barton Cup—the Ocean Cruising Club’s most prestigious award—for their project of completing a largely offshore circumnavigation of South America, during which they transited the Panama Canal; sailed to the Galápagos and Easter islands; extensively explored Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego; made two extended voyages to the Antarctic peninsula; visited the Falkland Islands, St. Helena and Ascension; and then returned to the Caribbean. They are currently meandering around Ireland and Scotland and planning for a summer season deeper into the northern high latitudes. They post passage updates to their blog, www.svzephyros.com; Facebook, sailingzephyros; and Instagram, sailing.zephyros.

OV:

What are the top skills voyagers need to know?

J&MS:

Successful voyaging requires one to be a functional multi-tool. That said, we are constantly improving our skills and learning new ones. In our mind, the skills most needed to enjoy the cruising life and to continue voyaging for a significant period are flexibility, resiliency, risk management, crew resource management and an insatiable curiosity about the world. Knowing how to sail your boat helps, too!

Things will go sideways some days. How your crew manages the situation and the fallout will be what matters. Solutions may require considerable creativity and flexibility. If you end up with an unplanned stop or delay, take it as an opportunity to explore a little and find a gem you would have otherwise missed—they might become some of your favorite stops.

OV:

What is your planning routine prior to a voyage?

J&MS:

We use Jimmy Cornell’s books to help map out our long-term plans and extended passages. Before undertaking any significant voyage, we research the area to understand the traditional routes and times of year that the passage is normally undertaken. We also start to look at how weather systems are developing and passing through at a very broad level. Once we are in the area that we expect to jump off from, we start watching the weather closely. Even before we are ready to depart, we will start looking for weather windows to materialize and see how they develop. We do this as much before the passage as we can so that we can understand how the weather systems in the area are presenting and then how they play out. Watching the voyages of other boats on similar routes can also be instructive.

We make sure that loose items are secured and that the boat is ready to go. We do engine checks, check the rigging, set up our series drogue, deflate the dinghy, etc. We make passages with clear decks. We provision and generally get ready to be offline for the passage ahead.

As everything comes together, we look for our weather window and try to time the final preparations and provisioning to what looks like will work for us. If something unanticipated needs to be fixed or the weather just doesn’t feel right at the last moment, we aren’t afraid to reset and wait.

OV:

What is the most valuable skill you have picked up while voyaging?

J&MS:

The schedule is only a guideline. You need to maintain flexibility and resiliency to adapt to the realities of any situation. Holding fast to a schedule without consideration of risks is a recipe for trouble. Damaged gear can be hard and very time-consuming to replace when cruising, so don’t break things trying to make a schedule.

OV:

Do you think the experience of voyaging has changed now that voyagers can stay more connected at sea?

J&MS:

Yes, we can plan and reroute voyages around weather. We do not (yet) have Starlink, but we do have an Iridium Go. We download weather files multiple times a day and readjust our plans based on any new information. We are able to see potential weather problems developing, monitor them and plan for what is to come. Additionally, we can track which forecast seems to be getting the predictions the most correct. The ability to download ice charts, buoy and ship observations, and the course and speed of other sailing vessels provides critical insights that make our voyaging more efficient and comfortable. Easy connectivity at sea can mean the opportunity to get technical support or stay connected with friends and family. This constant, easy connectivity at sea can provide reassurance for family, but it may also increase stress for you and them. We all need to unplug from the connected world sometimes, and long voyages shouldn’t be a missed opportunity to do so.

OV:

Does the pressure to stay on schedule sometimes contribute to you taking risks with bad weather?

No, we stay true to the voyaging rule that friends and family can tell us when or where they want to visit, but not both.

J&MS:

It can be stressful waiting for a weather window to materialize in that sometimes you are fully provisioned and eating your stock, burning to get going, while knowing it is better to wait for the right window rather than one that looks like it might just be good enough. Patience is a virtue. You may need to use those flexibility skills and risk management skills to accept a different weather window than you had originally hoped for, but that should be done only with a full understanding of the risks.

OV:

How do you handle provisioning? Do you have a system for determining the amount of food and water needed for a voyage?

J&MS:

We can be frugal with water, and have stretched our 660 liters for 45 days, but now we have a watermaker and tend to use water more liberally. The watermaker has certainly made life easier and more enjoyable aboard. We usually keep at least 350 liters in reserve when on passages or cruising remotely. We also carry about 40 liters of bottled water for emergencies. So if the watermaker stops working or needs repairing, we can begin rationing water until it is back in service again.

Fresh food is usually our limiting factor for how long we can remain remote. For provisioning, we have used spreadsheets, and we have a general feel for how much food we consume on a weekly basis. We tend to run the boat like a grocery store and keep a spreadsheet of where the provisions are stored. This is less needed in normal cruising as certain food items have their place, but when on long, remote journeys, it is useful to know how much we have and where we stashed it. We know others that do boxes for a week or two and rotate stores this way, but that hasn’t worked for us. We use bins for fruits and veggies and a deep refrigerator for meats and perishables. When preparing for a long stretch in remote areas, we search out a butcher to vacuum pack and freeze meats. With hard, frozen meats and vacuum packing, we can carry two to three weeks of fresh meat on board with just the refrigerator, at least in cooler climates.

Like most long-haul cruisers, we almost always have a fair amount of deep provisions that account for our emergency food supply. While on passages or in remote areas, we deepen the deep stores so that we have a buffer of about 50 percent of our intended provisions consumption. We make sure we have plenty of staples onboard—there will always be flour, rice and pasta at hand, as well as canned veggies and meats. Despite having two hungry teenagers on board and making 30-day passages a few times, we have never been low on food. We have been missing a green salad, but there has always been plenty to eat.

OV:

What do you find most challenging about ocean voyaging?

J&MS:

The biggest challenge is the separation from family and friends. We have been back to the U.S. only one time all together. Jon and Megan have each gone back separately, once each when needed in family emergencies.

OV:

Do you find celestial navigation useful? Do you ever do celestial sights during a voyage?

J&MS:

We think celestial navigation is useful, particularly noon sights, which are pretty easy. We have both successfully completed celestial navigation courses and used it back in our Navy days. However, we consciously don’t have a sextant aboard. In today’s cruising, there are just so many devices aboard that have GPS/GLONASS/Galileo/Beidou data that we are comfortable taking the risk. Should there be a major disruption to all the GPS and SATNAV services, the best place to be may be lost at sea. We do have dead reckoning tools aboard.

More useful than celestial navigation, in our way of thinking, is proper piloting and navigation skills. Electronic charts and plotters are fabulous, but we find that sailors often don’t fully understand how charts are developed or how to use charts for piloting. The plotter will usually guide you well, but sometimes it won’t, particularly if you try to cut the margins too tight or sail in less trafficked waters. We have also noticed that many sailors don’t seem to be able to use a plotter like a paper chart if something is off in the database or the current position plot. The charts are often still the correct geographical representation and can be used just like you would a paper chart, to include the plotting of bearing lines. Sadly, many electronic charts now include fewer inland details, such as towers, than the paper charts of old.

OV:

Who or what inspired you to go voyaging?

J&MS:

We both enjoyed sailing in our college years. We wanted to explore the world on our own terms and see parts of the world that are often missed. Additionally, the children were at ages that made it easy for us to take the leap. It has been a precious gift to be able to spend so much time together as a family unit.

OV:

What are your future voyaging plans?

J&MS:

We plan to explore Norway and Svalbard this summer, and then we shall see. The original plan was to cruise for three to five years. We are now in our seventh year sailing full time and nobody wants to stop.ν