the rocks.

My wife Anne and I were aboard our 26-foot sloop Starlight of Mersea, sailing fast through the Caribbean night, reaching along parallel to the waves with the self-steering wind vane working hard to keep her on course in the boisterous seas. It was about five in the morning. There was no moon but from the hatchway I could see the sails and steering gear by the faint starlight and the luminescence of the breaking wave crests.

A few years before we had found Starlight in Bob Vowell’s yard in Pwllheli in Wales and bought her for £1,600. Starlight was a Stella Class (stellaclass.org/technical-information/) wooden clinker-built seven-eighths rigged sloop of 26 feet overall length. She was the fourth built of the Stella class in 1960, designed by C. R. Holman. A real thoroughbred, she raced her first year in the East Coast Offshore Association series and won all six races!

We raced her in the Irish Sea and took a two-week cruise to Brittany and the Camargue. The seed planted in my mind by Joshua Slocum germinated and we decided to leave England and head for Australia. After crossing the Atlantic we spent five years in Antigua then sailed south down the Islands and reached Venezuela, where we found a wonderful unexplored land of milk, honey, and rum. After a wonderful stay we tore ourselves away to head for Panama and visit the offshore coral atolls of Las Aves on the way.

As we bounded along toward Las Aves, I checked the Sumlog mechanical speed indicator; it showed that we were making five knots and had done 60 miles. This distance tallied nicely with my mental calculations — we had sailed the equivalent of 12 hours at an average speed of five knots. This left 30 miles to go; at this rate we would be in the vicinity of Las Aves shortly before noon. I would have to take sextant shots when the sun came up to correct our course, because during the night the self-steering would only hold us roughly on an estimated “dead reckoning” compass course. The atoll is low and small so I expected we would sail right by it without seeing it and then have to start swanning around looking for it. This had happened to us several times already when sailing out to other offshore islands along the Venezuelan coast. Right now there was nothing more to do so I took a last look round. There were no lights to be seen; we had seen no shipping at all in this area and so I went back below to take another cat nap.

I jerked violently awake to a tremendous crash and sprang out into the cockpit in one startled jump. The crashes continued and the boat tilted over on its side on a rocky beach that I could see dimly in the faint light. Each wave bumped the boat higher up the beach with a kind of ratchet effect, leaning her steeply over on the port bilge and banging her side heavily on the rocks as heavy spray broke over us.

My first frantic thought was how to save the boat. Maybe I could try to carry a kedge anchor into the waves behind us. They were rushing out of the night and breaking heavily, staggering out into them with a 30-pound anchor would be a desperate struggle. I realized it was pretty well impossible to get the anchor out far enough to hold and anyway, even if I succeeded, we wouldn’t have enough power to use it to pull her off even using the sheet winch. Starlight was already solidly stranded, half out of the water on her side, only lifting slightly as the crests of the highest waves raced past her up the rocks.

“Grab the money and passports and stuff like that,” I shouted to Anne, who was hanging on to the steeply tilted cockpit staring horrified at the waves breaking around us. We threw a few things into a bag and I scrambled along the cabin roof to the bow where I found I could step off onto damp land as the prow was hard up against a small shelf of rock. It was starting to get light as the tropical dawn raced up and I saw that we had hit right slap in the middle of a small atoll — it could only be Isla Las Aves. About half a mile to the west there was a lighthouse but the light was not working. Half a mile to the east the island ended in a maelstrom of half-submerged reefs smothered with breaking waves. If we had hit them we would have probably been smashed to death. A mile either way and we would have missed the island altogether.

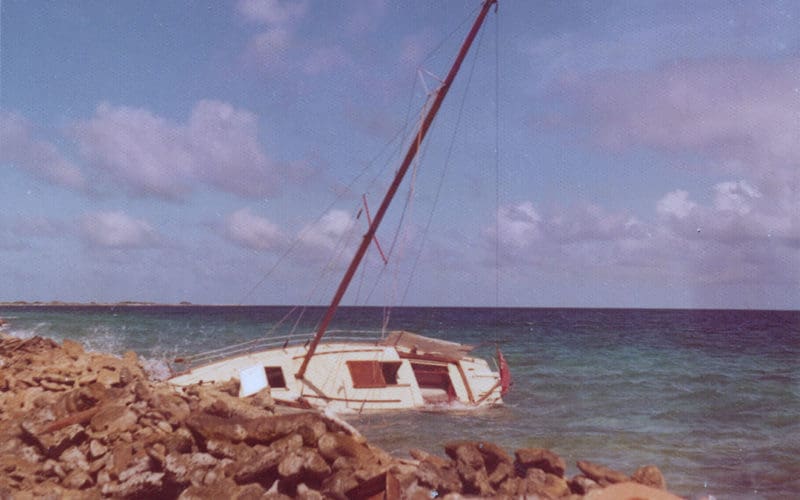

The relentless hammering on the bilge as the boat lifted on the highest surges soon opened up a hole in the planks and the boat half filled with water. The pounding stopped as she now had no flotation to lift her and she lay dead and desolate in the surf.

We worked hard for a couple of hours taking everything movable off the boat. Later we would use the dinghy to ferry everything from the lee side of the reef to an abandoned fisherman’s shelter on a nearby beach. We were now real Robinson Crusoes; we did not know how long we would have to stay on the deserted island before being rescued and might need all our food, water, and other stuff to survive. We had plenty of books, including James Michener’s Castaways.

Shocked and tired, we sat on the beach surrounded by all our worldly goods looking at the forlorn sight of our beloved Starlight stranded and broken in the surf. It was the end of our round-the-world voyage. “What the hell are we going to do now?” I asked.

“Well, we’ve got a bit of ice left, and some Scotch, why don’t we have a Scotch on the rocks?” replied Anne.

Later, I analyzed the navigation. This accident occurred in 1973, long before the advent of GPS. Position finding for small boats out of sight of land depended on celestial navigation, on using a sextant to take a pair of sights a few hours apart. One only got a complete position fix after the second sight, usually taken at noon.

As a result, we couldn’t normally determine exactly where we were before noon each day. The rest of the time we relied on dead reckoning, steering a course by compass.

When we hit the distance shown on the Sumlog of 55 miles, I estimate we had done an additional five miles at the beginning when the boat was sailing too slowly for the log to register. Our speed through the night must therefore have been about four and a half knots and we should have still been 22 miles away from the island. The most logical explanation is that a freak current swept us well ahead of where we thought we were.

Currents are variable and strong at times in these treacherous waters. Many ships and yachts have been wrecked on Las Aves, including a whole fleet of French galleons and a small tanker with all modern aids, including radar!

What is amazing is that while our distance made was wrong by 22 miles in 60, an error of thirty seven percent, our course made was precise to better than one tenth of one degree! If our course had been out by as little as one degree in either direction we would have sailed right by the island and never seen it.

A push from a freak current? A shove from the hand of fate? I don’t know. n

Cris Robinson is a delivery captain, worked in the petroleum industry, owned a shipyard in Venezuela, is a marine surveyor with more than 1,000 vessels surveyed and lives aboard his sailboat Ondine in Puerto La Cruz, Venezuela.