cruising to remote locations offers an

irresistible allure, however, it also carries with it a higher burden of mechanical independence.

The famed Norwegian polar explorer Roald Amundsen once said, “Adventure is just another word for poor planning.” In Amundsen’s time explorers were very much on their own, without the support of a vast electronic safety net and boundless rescue assets, and the best of them did everything in their power to avoid the unexpected; they had “everything in order.”

There’s something to be said for this approach, particularly where cruising vessels are concerned. As the manager of a busy boat building and refit yard for more than a decade, and 15 years as a marine systems consultant, I’ve learned many lessons, both directly and via my clients.

Several years ago, while transporting a customer’s 60-foot ketch, my wife and I experienced an engine failure. I heard a change in the engine’s note and instinctively glanced at the instrument panel and noticed the voltmeter was hovering just under 12. I knew something was wrong. While my wife took the helm I opened the engine box, where I immediately identified the problem. My heart sank: Remnants of the fan belt hung in shreds from the front of the engine. We were well off the beach, winds were light and so we ghosted along while I rummaged through the vessel’s spares locker for a replacement. Even though the boat was a 57-footer, she was used by her owner primarily as a day sailor, which meant her spares were limited to a few fuses and light bulbs and a quart of two of oil.

Lesson one learned: Never leave the dock without at least a quick review of onboard spare parts, which should include among other things, impellers, belts and fuel filters.

As I pondered our situation I heard the sails begin to slat, the wind had all but died now, and what little of it there was wasn’t from a favorable direction. The ignominy of calling for a tow made that a non-option, I’d never live it down.

While there were no spares, I did have my well-stocked tool bag. After some head scratching I managed to make a belt from a triple length of 3/16” flag halyard, reinforced with electrical tape and zip ties. The zip ties didn’t last; however, after a few iterations the “Mark IV” version worked well, enabling us to power for several hours until I was able to source and install a replacement belt.

Lesson two: Always have a good set of tools aboard, and always have a flashlight and a knife on your person.

On another occasion, while cruising with a client off the coast of Newfoundland in heavy weather, several hours from the nearest port, the high water alarm sounded. I opened the hatch over the main bilge and took a face full of chilly North Atlantic brine; the stuffing box was doing a very credible imitation of a garden sprinkler on steroids. I closed the hatch and directed the helmsman to throttle back. Because of the sea state it simply wasn’t possible to be without power for more than a few minutes. I asked the owner if he had spare packing aboard and, of course, he didn’t. I searched for a suitable alternative. We had plenty of line, but it was all synthetic and I was concerned it would melt and score the shaft, and none of it was small enough in any event. I finally decided I had what I needed to manufacture packing: a well-worn cotton T shirt and cooking lard. I cut up and rolled strips of T-shirt that equated the rough dimensions of waxed flax packing, and then slathered them with Crisco. I removed the remnants of the old packing and stuffed in the new jury-rigged version. But doing so between bouts of seasickness and having to back away when the helmsman signaled he needed to turn our head to the seas, proved a bit of a feat. Ultimately it worked and we limped in at reduced speed to Harbour Breton, where a fisherman was kind enough to give us some packing material, for which he’d accept no payment.

Lesson three: Be prepared to improvise, and be thankful for the kindness of fellow mariners.

I’m a high latitude junkie, so many of my most memorable fixes at sea have occurred in these regions. A few hours out of Stornoway, Scotland, bound for the Faroe Islands, the Fleming 65 I was cruising aboard sounded its hydraulic fluid high temperature alarm; the vessel’s stabilizers were hydraulically controlled, making this a critical issue. One of the crew suggested we simply shut down the system and press on. I objected for several reasons; one, the hydraulic fluid requires cooling whenever the engine is running, and thus the pump is turning (it was not equipped with a clutch) even if the stabilizers are disabled. Two, the weather forecast included a 12-hour stretch of “unsettled” conditions, so the stabilizers would be needed, and I’m prone to seasickness, adding a sense of urgency to my repair skills.

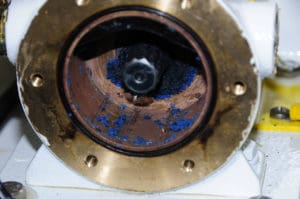

The problem turned out to be a failed impeller, which is normally a straightforward enough replacement, and there was a spare impeller aboard. However, in this case, the installed impeller was a plastic composite, so it had melted rather than breaking up, fusing itself to the pump. The captain and I brainstormed for a bit while drifting in the lee of the northern tip of Lewis and Harris Island. We ultimately scavenged a pump from the hot water circulation system, pressing it into service as a makeshift raw water pump. While the pump was not designed for the application, it filled that role until we reached Iceland two and a half weeks later. From this passage onward, I have equipped many vessels with a pre-plumbed back-up hydraulic cooling pump. Had the failure occurred later in the voyage, while crashing through 12-foot seas it would have been a far more difficult task.

Amundsen also said, “Victory awaits him who has everything in order — luck, people call it. Defeat is certain for him who has neglected to take the necessary precautions in time; this is called bad luck.” Failures like those described are anything but bad luck, they represent nothing more than a lack of preparation, and are thus entirely avoidable.

Regardless of whether you’re setting off to cross an ocean, or just the bay, first ask yourself what you will do in the event of a failure of a critical system, a belt, impeller, fuel filter, raw water hose, steering or stuffing box. What will you need to carry out repairs, even if temporary? Only after you’ve answered those questions should you cast off your lines and get underway. n

Steve D’Antonio is an ABYC-certified Master Technician and sits on ABYC’s Engine and Powertrain, Electrical, and Hull Piping Project Technical Committees.