For voyagers, one of the most dangerous scenarios we face is winding up in the ocean, separated from our vessel. Clearly voyagers are concerned about this, as every marine store stocks a long list of devices such as personal locator beacons (PLBs), man-overboard modules, AIS signal devices, lights and so on.

But these devices are reactionary. They simply do not solve the initial problem: going overboard in the first place.

We cannot eliminate the inherent hazards of sailing, but we can we mitigate them. We do this through training and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE). As with any jobsite, we need a last line of defense against harm. Hard-hats protect our skull, safety glasses protect our eyes and jacklines keep us on the boat…or do they? The average voyager might say: “I thought we kept those below in case of a storm. I can just hook them up if it gets bad, right?” Wrong. Under stress, we will do what we always do — rely on our habits. If we aren’t in the habit of using jacklines, they won’t work for us the way we want them to.

I am going to share my jackline system. But first, let’s look at a few examples of why we need such system in the first place.

In 2012, Low Speed Chase, a 38-foot sailboat, was tossed against the rocks in surf conditions. Five of the eight crew died. I met one of the survivors at a Safety at Sea course. He bravely shared his story with us in the class. He said that his payoff from talking about his experience was the hope that others would not repeat the mistakes made onboard that day. We can do him justice by being teachable and taking action, safety-wise, on our own boats.

“Crews need to talk as a team about tethering strategies.” he said. “One person overboard puts the entire crew at risk, as others might need to unclip to quickly maneuver the boat back to their location.”

His words align with my concerns about common practices with jackline use, specifically not using them to begin with.

The full report on the incident can be found at the US Sailing site (www.ussailing.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Farallones-Report-FINAL.pdf) and drives home the importance of staying with the boat.

Safety mindset

My second example is about mindset. During our safety inspection for an offshore race, the inspector criticized our jackline installation. His concern was not that they were ineffective, but that using multiple attachment points (as I will describe shortly) “was too slow.” I stated the safety benefits of the system and he agreed but insisted they would be too slow and difficult for crew to use. I finally understood that his point was not of safety but speed. He saw the many attachment points as a hindrance to racing, because his priority lay with maximizing speed and making it secondary to safety considerations. This was confirmed when he thought the large fire extinguisher onboard could be left behind because it was “too heavy” and it was not required for the race.

I don’t mean to be hard on the guy. But in his mind, jacklines were required equipment to participate in the race. In my mind, jacklines are a tool to keep us inside the lifelines and a contract with our crewmates that says, “When you come to relieve me, I will still be here.”

Most of us sailing outside of major races have a limited budget and green crew, with most watches short or singlehanded. This means sail changes, reefing and the like are handled by one or two crew.

My last example is a tragic story I heard in Alaska, years ago. A man near Sitka died when he was dragged by his own boat. As I heard it, the jackline arrangement allowed him to pass over the lifelines and into the sea where he was dragged along in the water. His inexperienced crew member did not know how to stop the boat and focused on trying to recover him instead. He failed to pull the man aboard and the man drowned, right in front of him. This happened in relatively calm weather under sail.

Some quick math

Some quick math

Let’s do some quick math. On a typical jackline installation, one long jackline is run the length of the deck on each side of the boat, a foot or so from the toe rail, enabling crew to clip in once and travel fore and aft unhindered. This jackline allows a deflection of a minimum of two feet, like a bow string being pulled. The longer the boat, the greater the deflection.

If the crew is wearing the standard, commercially-available, six foot tether, this puts an overboard crew in the neighborhood of eight feet beyond the lifelines under load. Typical boat lifelines are two feet high. This means that if you or your crew goes overboard wearing this setup, you will be dangling six feet beyond the lifelines. This is one step better than being lost at sea, but is still a big and completely avoidable problem.

Any crew going to help in recovery will need to use the same deflected and loaded jackline. If single tethers are used (common and commercially available), crew will need to un-clip to pass each other while they sort out the problem, which now likely includes stopping the boat.

Even a race crew could do with a better system. Remember, they want to go fast. Dumping canvas and rescuing a dangling, dragging, and probably drowning crew member does not sound fast.

Properly run jacklines, however, with good crew training (daily use) are as fast and more effective than the common arrangement.

Firstly, deflection is minimized if the line is attached at close intervals and the intermediate attachment points isolate the stress. Which means that if a crew member applies tension to the line, the rest of the line is unaffected and available for use.

Dual lanyards allow for crew to pass by each other, without being un-clipped, or stuck beyond their own reach. Quick disconnects allow for an emergency exit from the jacklines in unforeseen emergencies. Most important, no lengths of our tether, or deflection in the jackline, are so great that our bodies can pass over the side.

Stories and encounters like these are all good reminders to train your crew and stay on the boat. But when I look at the standard for how to do that, I am concerned.

The way we approach jacklines and tethers needs to change. We need to embrace them as the tools they can be. We need to run them and train with them, until working on deck, clipped-in, becomes our new normal. Only then will we be held on deck and free to work with our hands, feet and sometimes teeth as required.

The following method was developed by my myself and fellow crew members. I have implemented and used evolving versions of this method over tens of thousands of miles from the High Arctic to the The Intertropical Convergence Zone. These voyages have varied from crewed to solo, races to deliveries, with great success and no injuries beyond the use of a band aid. So needless to say, I like this system. It represents the best of what I have learned so far on the subject.

The following method was developed by my myself and fellow crew members. I have implemented and used evolving versions of this method over tens of thousands of miles from the High Arctic to the The Intertropical Convergence Zone. These voyages have varied from crewed to solo, races to deliveries, with great success and no injuries beyond the use of a band aid. So needless to say, I like this system. It represents the best of what I have learned so far on the subject.

Take your string and tape with you to the bow to plan your layout. Moving down the length of the boat, tape your string to each point where you plan to attach the jackline. This allows you to see, touch and evolve your plan, pre-installation.

In the following example, I show a 47-foot Stevens with hard dodger, hard tender on the foredeck, a mast corral and through-bolted aluminum handrails. These jacklines, installed about three months earlier, sailed over 3,000 nautical miles in tropical weather.

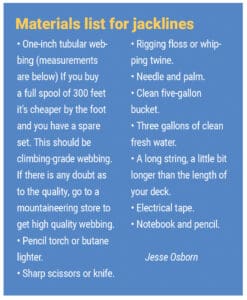

I estimated the deck at 45 feet. Then added 30% (13.5 feet) to make up for corners, knots and the like. That gives me 58.5 feet. I rounded up to 60 feet and cut my first jackline.

Harnesses and lanyards

Harnesses and lanyards

Both harnesses and lanyards are available commercially at marine supply stores. Most harnesses are integral with lifejackets designed for offshore use. The Spinlock-style shown in an accompanying photo is comfortable, effective and safe.

A dual-leg (two clip points) lanyard is an absolute must. Many commercial tethers have a six foot leg and a three foot leg, or some variation of long and short.

In my opinion six feet is way too long. We need to be able to reach our last clip point and release it while clipped in to the new point.

Make the length of your short tether leg to reach from harness attachment to your outstretched hand. This is your close work lanyard. Label it with whipping, textured for feel so you can identify it at night.

Now make your long leg tether to reach from harness point to your ankles. This way you can clip in and stand upright.

With this two-tether method of different lengths no matter where you clip, either can be reached by one of your hands and some bending.

Choose your clips well. I prefer stiff spring stainless steel clips often found on old survival suits. Aluminum clips corrode. If you don’t like them you can change them later.

The harness point should be a quality quick release with a small lanyard. This allows for a release from the jackline in an emergency, an absolute last resort, where the line becomes a hindrance, such as exiting a sinking vessel.

My current setup has a 5/16-inch Dyneema, double-brummeled and tapered. My other set up is double braid and I’ve made a few three-strand. All of them work well.

As a bonus, If I don’t get too fat, I can wrap them around my waist and clip them together when briefly below. Currently they are a couple of inches short, so I leave the setup clipped inside the companionway, then re-attach the quick release when heading topside.

Test it out

Put on your harness and make a dry run all over the boat, station to station. Try to fall overboard. Can you? If you find that it is possible, then fix that. Involve your crew and make sure they are set up with a matching harness and tether to their personal measurements. Add or change the jackline if you see an error, but don’t get too particular here. What makes sense at the dock rarely makes sense at sea. Now let’s go sailing.

This is a training run. No destination. The focus is jackline use, moving from leg to leg with double lanyards, never un-clipped from the line and doing all the work you normally do at sea. Try all your sails. Reef, shake out, hoist and stow. Clip in at the breakwater entrance and stay clipped in until you return to the harbor entrance.

Have a meeting, take notes, make changes. Reset them wet as before (see sidebar). Then stitch the ends down, with a flat interlocking square pattern. This will secure the ends, clean up the appearance and can be cut without damaging the webbing, should you wish to make changes.

Practice using the jackline as support. Clipping both legs at an angle can keep you from swinging. Leaning into the line tension can hold you steady while you work.

Once the lines are installed, they stay on for the season. Use them every voyage and all the time with no exceptions.

Next time the rig howls like a wolf pack and the needle like spray leaps from the waves, you’ll feel much more secure and effective. And your crew will sleep soundly knowing you are clipped in and on deck. n

Jesse Osborn owns Seven Seas Sailing Logistics, which provides captain services, consulting, teaching and project management for sailboats.