My husband and I bought Ora Kali, a Sabre 30, in June and just a month later left New Jersey to take her to Maine.

We had delivered less prepared boats than Ora Kali; the owner was planning to slip her himself when we made the deal. But the marina was up a shallow tidal creek where we couldn’t do any preparation. So our first foray was the day we dropped the mooring lines and negotiated two opening bridges to get into Raritan Bay. That short sail showed we were not ready to go offshore. We needed shakedown time which meant taking the only other option, an inside route up Long Island Sound. This in itself was not a problem though it required us to plan carefully because of the currents around New York City.

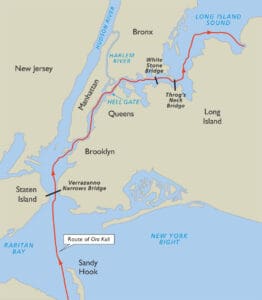

Eldridge Tide and Pilot Book covered the 34 miles we had to traverse in five current and tide tables and a set of hourly current diagrams. The course cuts first across Lower New York Bay south of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge, where the pinching arms of Sandy Hook in New Jersey and Rockaway in New York guide the Atlantic in and out of New York Harbor. On the other side of the voyage, Throgs Neck marks the opening to Long Island Sound, whose waters also move into and out of New York. In between are lots of inlets, rivers and creeks.

Key to successful navigation is timing a boat’s arrival at the Battery at the southern tip of Manhattan. Twice a day, as great masses of water flow into and out of New York, the change in water height isn’t huge compared to other East Coast points. But current, the horizontal movement of the tide, around New York can be significant. In the East River’s notorious Hell Gate where everything meets — New York Upper Bay, Long Island Sound, and the Hudson River via the Harlem River —it can reach 5.3 knots. Even for commercial vessels like tugs with barges, the area’s unpredictable eddies and currents can make navigation a challenge. For sailboats passing through it is imperative to time the passage carefully.

Crossing the lower bay

Our starting point in Atlantic Highlands was 12 miles south of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge and another six miles from the Battery. Navigator wisdom says to be at the Battery 1 ½ hours after low tide to carry the favorable flood up the East River. We pulled anchor at 0800 which should have left time to get there by 1300 even at our modest boat speed of four to 4.5 knots, but I hadn’t thoroughly examined Eldridge or I would have noticed a big error in my timing. I couldn’t have done much about it, but at least I would have been prepared.

We exited the anchorage well before our friends on Luckiest, a Morgan 44, with a good wind to start out; in fact the log shows we reefed the main. An hour later the wind was dying. We shook out the reef and by 1000 had turned on the engine — an underpowered and elderly Westerbeke 13. We kept the mainsail drawing for as long as possible but even motorsailing the difference between Ora Kali’s speed over ground and speed through the water grew uncomfortably large. When the GPS showed us making two knots over the bottom compared to four through the water I looked at Eldridge’s current diagram for New York Bay and saw that we were battling a significant ebb tide out of New York. We could see Luckiest in the distance behind. Then they caught up and passed us, as did what seemed an entire fleet heading for the same afternoon date with Hell Gate. The current looked weakest at the edge of the channel but when we crawled up to the starboard pylon of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge we still had a knot or so against us and were the last boat to arrive. Once we exited the great bridge’s shadow and left the roar of overhead traffic the current finally eased and we slid along the seawall of Brooklyn, marveling at the huge, busy harbor which never ceases to offer interesting sights. Suddenly the VHF came to life.

“Ora Kali, your friends are here,” Luckiest called to tell us.

Against the busy backdrop of anchored ships and a looming grey sky I distinguished a sailboat heading toward us. It crossed behind Ora Kali so we could wave and exchange greetings, then took up position just off our quarter. It was Cheryle and George on Intended Consequence. Tom and I spent many pleasant afternoons on the Catalina 320 which they kept on the New Jersey side of this very harbor. George is a retired helicopter pilot and it felt now like we had a wingman providing escort. As another large sailboat came from behind and passed us I didn’t feel so alone in being small.

No route planning

The distraction turned out to be unfortunate. When Intended Consequence left I turned my attention to the harbor ahead and realized too late that I had not done route planning for the next part of the trip. In contrast to my preferred way of doing things with dedicated GPS and electronic computer charts and paper planning charts, Ora Kali came with a Raymarine Dragonfly chartplotter at the helm. It was too late today to figure out why, when I finally thought of putting in a waypoint, it was stuck on a zoom that showed little more than the area right around the boat. Our excursions on Intended Consequence had been timed for pleasant good weather, not this looming gray, not squalls like the one about to hit as they peeled off. Though I often helmed the Catalina I hadn’t paid much attention to the confusing welter of harbor buoys. I needed Tom for eyes and ears, which meant he couldn’t go below to start the electronic charts running on the computer because I hadn’t showed him how Open CPN worked and, well, we were in for a penny in for a pound anyway.

We drew abreast of Governors Island with workboats crossing the river making the harbor seem like a bumper car park. From our day sails on Intended Consequence I was aware of the waters around Governors and comfortable enough to take the inside on Buttermilk Channel and follow the wharves of Brooklyn, though it meant keeping a sharp eye out for the crossing traffic. We passed two green cans in the channel, leaving them to port.

As it happened Ora Kali popped out of Buttermilk Channel below the Battery only a half-hour late but by then the tide was in high flood and soon sucked us up the East River, where we couldn’t turn around even had we wanted to. We passed a red buoy and a green buoy, leaving them both to port as they clearly marked the main channel around the Battery, before entering a winding stretch lined by concrete seawall and marked not by navigation buoys but by three noisy bridges. Going up the East River on a Circle Line tour is a much better way to actually see New York City. From water level I was able to glimpse odd canals and offshoots full of workboats and noticed both a large number of ferries crossing between Brooklyn/Queens and Manhattan and many new buildings that had gone up on the east side since we last passed through in 2000, built right down to the water with strips of park and joggers and dog walkers.

Miles before Hell Gate Ora Kali started bounding over tide rips and whirlpools at the entrances to various side creeks and channels that required careful control of the helm. We last navigated the East River on our Peterson 44, Oddly Enough, years ago traveling south in thick fog, and I hugged the Manhattan shoreline and communicated by VHF with the workboat traffic. Visibility today was good and there was so much traffic we didn’t bother with the radio and I hugged the Brooklyn side to stay out of the way.

Potential disaster

This proved to be a third mistake that could have had bad consequences. While the East River has been scraped clean of bottom hazards, it is not entirely free of obstacles. Four miles from the Battery is Roosevelt Island, a narrow chunk of land almost two miles long with the ruins of an insane asylum and smallpox hospital on the south end and housing on the rest. Heading south on Oddly Enough and following the shoreline I automatically left Roosevelt Island to port. Heading north with the Brooklyn/Queens shoreline also put the island to port, but without usable charts I missed the fact that this is the dangerous side of the island, not because of water depths but because two-thirds of the way up is a lift bridge with a vertical clearance of only 39 feet. If the bridge was closed we would not be able to turn around or stop in time with the current running at several knots. Luckily Tom noticed my mistake and sang out in time for me to crab across to the correct channel. An hour later that maneuver would have been impossible.

By the time we reached Hell Gate the air was filled with mist from churned up water and Ora Kali was doing 10 knots over the ground. The name Hell Gate sounds appropriate but in its original Dutch it meant simply beautiful strait. It was an exhilarating rush, especially because we were still making split second decisions about which way to go when we reached the intersection where the Harlem River branches off to join the Hudson River around a seemingly random island named Mill Rock which is all that remains of the Army Corps of Engineers’ 70-year rock-clearing project. It’s hard to pick out the fine details of navigation against a busy city skyline made up of many confusing shapes. The moon was in a low phase but there’s never much slack at Hell Gate and when we passed through into the next straight stretch the current was running between three and four knots with us.

By this time the sun had emerged. North and South Brother islands looked green and inviting, and I’d gotten used to the scale on the Dragonfly chartplotter well enough to sort out the confusing mess of markers and channels around them and Rikers Island. Here again New York had offloaded its unsavory activities onto river islands, turning North Brother into another hospital for “quarantinable” diseases and using South Brother for its first refuse dump. Both are now waterbird sanctuaries. Rikers Island has been a prison since the 1930s, with a history of violence and mistreatment of prisoners.

Shutting down the engine

Beyond the islands the river widened. The engine had been running at full tilt for seven hours, rattling away underneath the cockpit in an uninsulated engine space. In the relatively placid reach we raised the main and rolled out the jib and turned it off. Ora Kali sails much better than she motors, but I was too optimistic about the wind speed and angle and we ended up having to make short tacks into what looked like a wide-open bight on the north side of the river between the Bronx-Whitestone and Throgs Neck bridges but became a turning basin for a tug and barge. Here we were also embarrassingly caught by a yellow junk-rigged ketch, the last boat to beat us.

at the helm of

Ora Kali.

We sailed under the Throgs Neck Bridge into upper Long Island Sound, a crowded piece of water familiar from years spent at Harlem Yacht Club on City Island. It would have been interesting to visit our old club, but we had picked out Port Washington in Manhasset Bay for the night on the advice of Luckiest who had more recent experience hanging in the sound with family in between trips up and town the East Coast.

Home in Maine and thinking over our trip I wondered about that business around the south end of Roosevelt Island. I had been missing the chart for New York Harbor in the East River but it didn’t actually clear up the mystery when I had a look. There’s a distinct lack of navigation markers in the southern part of the East River. Going north after passing two greens and a red numbered 1, 2 and 3 off the Battery there’s nothing for 2 ½ miles until a single red buoy, no. 18. On the basis of “red right returning” I would have left this buoy to starboard if I’d noticed it. The next markers, under Roosevelt Island, are a green-over-red and a green. Leave them to port, correct? Wrong. Just south of no. 18 the buoyage changes, and a northbound vessel instead of heading home is heading to sea again, i.e. to Long Island Sound.

Personally I think this is an error on the part of the Coast Guard, the agency in charge of navigation aids. The point of having colors, numbers and shapes is to give the mariner visual directions. The addition of a green “17” would have made it clearer what happened. Even on the nautical chart the only indication of the change is that the buoy numbers start going down north of no. 18. The paucity of markers and with so many in-between numbers missing indicates perhaps there were more in the past. n

Contributing editor Ann Hoffner and husband Tom Bailey cruised aboard their Peterson 44, Oddly Enough. She’s now based in Sorrento, Maine.