Practice this skill before you need to use it

When I was 21 years old, I worked as a deckhand on the American tall ship Rose. Whenever we would depart from a port, the afterguard would have us practice various safety drills, ensuring we knew what to do should something terrible happen. I remember standing on deck after wrapping up a fire safety drill when our captain suddenly appeared with a coconut in his hand, announcing we were about to conduct our man overboard rescue drill.

Gathering us around, he stood there holding the coconut up high for all to see while explaining that a coconut is very close to the size of a human head. Then without warning, he tossed the coconut into the water as he shouted, MAN OVERBOARD! Immediately, everyone on deck shouted MAN OVERBOARD as life rings were thrown into the water. Repeating the call is meant to signal acknowledgment and ensure that everyone has heard the call. One of the crewmembers then shouted, “I’m the spotter,” as she extended her right arm straight out like a weather vane, pointing at the coconut in the water. She stood there erect, never taking her eyes off of it and turning her body so that she was always pointing at the coconut. Her pose provided the visual reference needed by all on board to know where the coconut was relative to our ship because we were sailing away from it and completing a fast 180 degree turn on a 180-ft long square-rigged ship is no easy feat.

Not much about how I conduct safety drills has changed for me in the 20 years since first using a coconut as a stand-in for a human head. I now call the MOB a crew overboard drill (COB). Fortunately, I have only had to rescue one live person out of the water in the last 20 years. The circumstances of that rescue were relatively easy because the sails were down, and we were already under power. The person in the water was not injured and was wearing an inflatable PFD. An inflatable PFD, like a Mustang HIT, is invaluable piece of gear if you’re unlucky enough to go over the side.

Recently I purchased three coconuts and rounded up two members of my summer racing crew to join me in practicing COB drills on my sailboat. We started the day by rigging the boat up just as if we were going out for a Wednesday night race. This way, we could see how prepared we truly are for rescuing a person out of the water should the unexpected happen. We always have a VHF handheld radio and cell phone on hand at the wheel. A Lifesling is mounted to our stern pulpit with the bitter end of the retrieval line tied with a bowline to the base of the stern pulpit. I have a great affinity for the Lifesling because it is easy to deploy, has a 150-ft run of floating retrieval line attached to the floating sling, and comes in a nicely designed white cover. We also have a boat hook we keep in the lazarette. If you have a steering pedestal-mounted chart plotter, it is a great idea to take the time to learn how to activate the COB function. This function creates an immediate GPS marker, so you have an event reference on your plotter.

I also have a hinged stern boarding ladder and keep two red throwable foam cushions on hand in the cockpit when cruising. They are type IV flotation devices, meaning they are not intended to be worn. They have 16.5 pounds of buoyancy and are easy to throw overboard, adding visual markers to where the COB occurred. When doing any long-distance cruising or racing, we rig up jacklines and wear inflatable PFDs with lanyards for clipping into the jacklines.

To maximize our drills, I divided the exercise into two segments. For the first, we motored out into the middle of the bay to be free and clear of any other boats. I engaged our autopilot and brought our speed up to five knots or 8.44 feet per second. At that speed, it would only take six seconds for the coconut to be about 50 feet off our stern after being deployed, not accounting for drift caused by the wind and current. The conditions were moderate with a slight swell and about five knots of breeze. We dropped the coconut in the water and took pictures of it at one-second intervals to see how fast a person in the water could disappear. After five seconds, the coconut started disappearing in the minor chop. After 20 seconds, nobody was able to spot the coconut. Learning that meant I would need to be able to fully execute my turnaround in less than 20 seconds if I did not want to lose sight of the coconut.

We next rolled into segment two of our COB drills by setting our sails to practice our retrieval skills. In a perfect world, we would roll the jib up, start the engine, drop the mainsail, and turn the boat around to go pick up our COB. Unfortunately, when it comes to sailing, we can’t always do things the easy way. Much to my dismay, I have observed that COB drills, if practiced, are only practiced only in calm or ideal weather conditions. This may be okay for the fair weather sailor who limits outings to cruising close to home on perfect condition days. What then about the sailor who travels long distances or encounters an unexpected squall?

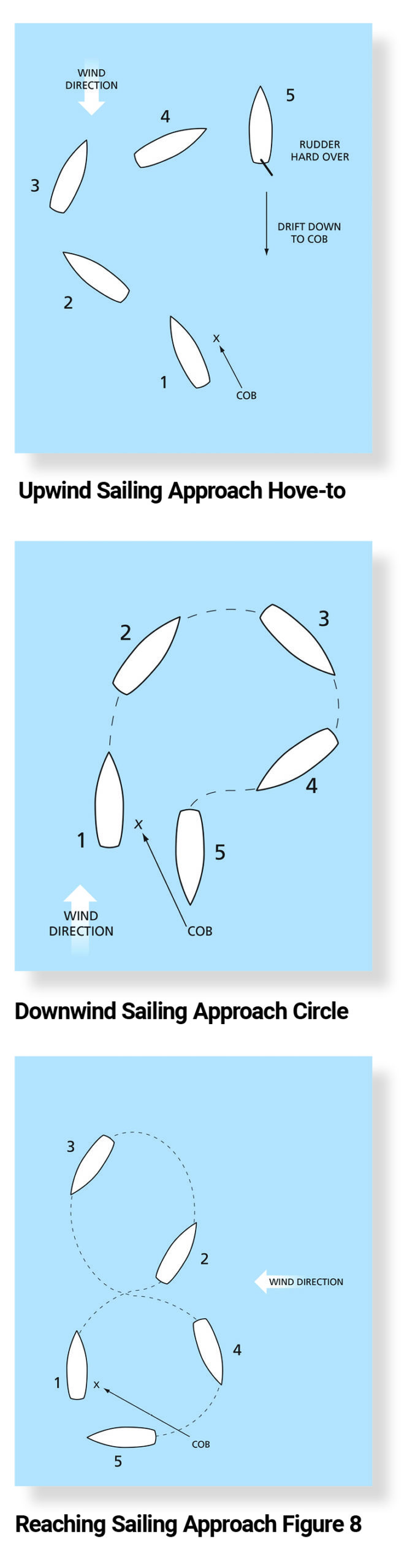

There are many tried and proven methods for successfully rescuing a person from the water. Methods aside, I always start the engine for all COBs and strike as much sail as possible. My boat has a roller furling jib, and I can easily roll it up myself as I maneuver the boat back towards the COB. My approach to a COB is thinking about the pros and cons of the different maneuvers and how they apply to the point of sail I am on should a person fall overboard. I also think it is imperative to consider the capability of my crew. For these reasons, I break up COB procedures into three categories: upwind sailing, downwind sailing, and reaching.

Upwind approach

Upwind approach

For me, the easiest COB method is a quick tack followed by heaving to. This method is best used if sailing upwind when the COB event occurs. This is also an excellent method to use if sailing shorthanded. When the COB occurs, I immediately start the engine while tacking the boat without releasing the active jib sheet which will become my weather jib sheet after completing the tack. When I am through the eye of the wind, I blow the mainsheet and turn the rudder hard to weather as if trying to tack back over. The combination of the backing jib and having the rudder hard over stalls the boat, allowing me to drift back down to the person in the water.

Downwind approach

If I am sailing downwind, and a COB happens, I immediately start the engine and sheet in all sails so they will be trimmed for close hauled sailing as I swing the boat around 180 degrees back towards the COB. If the spinnaker is set, I focus first on lowering it to the deck if it does not have a sock. If there is a sock, I drop the sock, not worrying about lowering the halyard during the maneuver. Note: if flying a spinnaker, you will likely not have a jib up, which will mean your best-controlled approach will be under power.

Reaching approach

If I am sailing with my beam to the wind when the COB event occurs, I have the option to approach the COB using the upwind method, or I can sail a figure eight to intentionally give me some distance for a more calculated approach. This method may be ideal if the spotter can maintain a good visual on the COB, and I am confident that the COB is not drowning. I like this approach when I have a competent crew on board because after jibing, the sails are immediately sheeted in close hauled to slow the boat down and reduce the need for much handling on the final approach. With the sails sheeted in tight, we can sail downwind towards the COB in a slow and controlled fashion. I can undershoot the COB in a worst-case scenario and come up hard for an alternate pick-up attempt.

The thing about a COB is it will most likely happen in a less than ideal situation. In fact, count on it happening at the worst possible moment. Making time to practice COB drills will teach you how to lead your crew and how best to approach the situation with your boat. It may feel silly to talk about what to do if a COB occurs, but I always make a point to discuss what should happen in the case of a COB every time I take my boat off the dock. ν

Will Sofrin lives in Los Angeles and is a graduate of IYRS School of Technology & Trades. He sails his Pearson 33-2 in Santa Monica Bay.