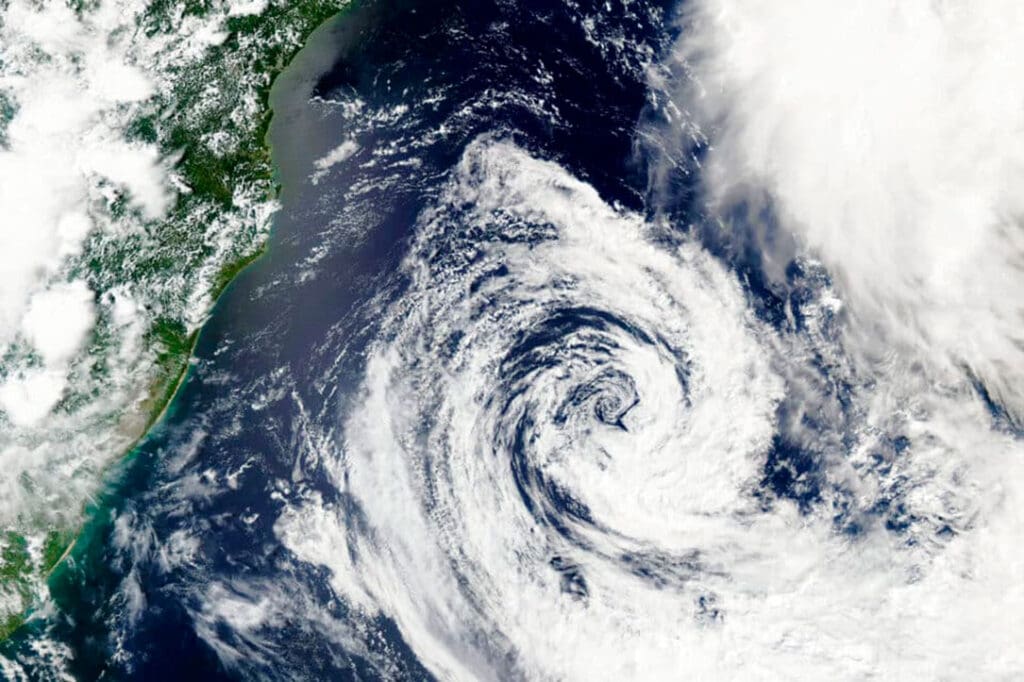

forms off the coast of

Argentina in the South Atlantic Ocean on February 22, 2024.

On Feb. 18, an area of low pressure just off the coast of Rio de Janeiro was identified by the Brazilian Navy Hydrographic Center’s Serviço Meteorológico Marinho as a subtropical depression. Two days later, it became a tropical depression and that evening was named Tropical Storm Akará.

This was surprising news. Tropical storms are uncommon in the South Atlantic Ocean, leaving the impression they don’t exist. While there’s no official South Atlantic season, tropical weather does occasionally form between December and May during Southern Hemisphere summer and fall. NOAA’s Office of Satellite and Product Operations makes projections of tropical storm formation and gives positions of identified storms but doesn’t track them.

South Atlantic Ocean water is generally colder than in the north, thus less likely to fuel tropical cyclone activity. Strong winds aloft create greater wind shear, which generally prevents storms from gaining height and therefore strength.

Still, South Atlantic storms are not as rare as the “A” in “Akará” would imply. Brazil’s list of potential names has already gone around. Two tropical cyclones, Catarina in 2004 and Iba in 2019, made global news, Catarina as an extremely rare hurricane and Iba as a tropical storm. Short-lived Anita in 2010 and 01Q in 2021 were also tropical storms.

Most of the named storms on Brazil’s list were not, in fact, tropical but subtropical, with a large, cloud-free center of circulation and very heavy thunderstorm activity in a band at least 100 miles from the center. Subtropical storms form from extratropical storms (blizzards, Nor’easters and ordinary, mid-latitude, low-pressure systems) that migrate into the subtropics, the geographical and climate zones lying between 25 and 40 degrees north and south of the Equator. If a subtropical storm remains over warm water for several days, the core starts to go from cold to warm. It may become fully tropical if thunderstorm activity builds near the center, bringing the strongest winds and rain closer.

The western South Atlantic is rarely travelled by recreational sailors, and then generally by those on circumnavigations via Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn. The current Global Solo Challenge race boats must head up the South Atlantic to finish in Spain. The race frontrunners, Cole Brauer and Philippe Delamare, were both home and had passed the 30s 41w position for Akará by the time it was declared, but in the grand scheme of things, not by much. They expected to encounter storms in the Southern Ocean, but moving forward, South Atlantic tropical weather also may have to be considered. Boats must round Cape Horn by March 31, which means the bulk of racers will still pass Brazil during its autumn.

Whether Akará is a sign of climate change and ocean warming is debatable. Perhaps the world is simply paying more attention to South Atlantic weather.