If you think wind vane self-steering rigs are on their way out, think again. The biggest producers of these mechanical wonders continue to refine their products into sleeker, lighter, more effective vane gears that keep this energy-saving technology a must-have among offshore cruising vessels.

Servo-pendulums, comprising the majority of vane steering systems, plus trim tabs and airvane-powered auxiliary rudders, continue to prove their worth over thousands of miles of cruising in the lightest airs to the most severe sustained gales. Some vane gears tend to work better in stronger winds, while other systems seem to be better suited to the vagaries of light, shifting breezes.

Yet one thing is certain: all of these wind-powered steering systems can be trusted to last a long time and be a reliable, electricity-free form of self steering.

|

|

Courtesy Scanmar |

|

A swing gate Monitor unit on a vessel is strong enough for crewmembers to sit on when open. |

Wind vane steering systems

To re-cap briefly what we may have learned about wind vane self-steering, these devices fall under three categories: servo-pendulums, trim tabs and airvane-powered auxiliary rudders.

The typical servo-pendulum system combines the forces of both wind and water to control the vessel’s rudder via double-braided control lines. As the vessel sails toward or away from the wind, an airvane dips to one side, activating a push rod that turns one side of the servo blade against the rush of oncoming water. The servo blade immediately swings to one side, pulling the tiller or turning the wheel until the airvane is standing straight and the vessel is on course.

It is actually much simpler than it sounds and even simpler to deploy and maintain. Our 1966 Cal 30 Saltaire completed a circumnavigation by way of two canals with a Fleming Global 301 servo-pendulum, requiring only the occasional changing of frayed steering lines and broken airvanes, which I cut from thin pieces of plywood. Through every kind of weather, from light airs to sustained gales, the airvane faithfully bowed under the wind, pressing the push rod and commanding the tiller at the precise moment the vane sensed a change of course.

During a sustained mid-Atlantic winter gale, the vane gear kept Saltaire surfing straight down 25-foot combined seas with nary a worry about broaching and capsizing.

|

|

Courtesy Scanmar |

|

Scanmar’s Monitor servo pendulum model can be installed with swing gate mount to access the stern. |

One over-arching advantage of servo-pendulum technology, aside from yaw prevention, is their adaptability to steer virtually any size of oceangoing yacht. The Navik, built by Plastimo in France, weighs a mere 30 pounds and would be perfect for anything from a Catalina 22 to a Baba 30. At the other end of the spectrum, the Windpilot Pacific Plus II can be fitted to a vessel up to 60 feet LOA.

A trim tab system comprises a narrow foil, like an elevator on an airplane, usually connected to an auxiliary rudder. While trim tabs operate in virtually all kinds of navigable weather, they are more at home in light airs where a servo-pendulum may not be able to draw sufficient steering power from slow-moving water. Don’t be fooled, though, by their seemingly delicate construction and operation. Trim tab systems, even homemade versions, have finished many circumnavigations and continue to draw a large following among seasoned offshore sailors.

Finally, the airvane-powered auxiliary rudder uses small reduction gears to convert air force directly into steering power. This type of unit, available exclusively from Hydrovane, is completely self-contained and operates in anything from a light zephyr to a sustained force 9 gale.

Servo-pendulums

Dr. Stellan Knöös is one servo-pendulum wind vane designer and manufacturer who never sleeps. From his first creation, the self-contained Sailomat 3040 servo-pendulum and auxiliary rudder that debuted in 1974, to the pendulum-only 536, 601, 700, 701, and then 760 released in 2008, Knöös continues to obsess over the most minute details in foil design, his patented “spherical-joint” systems, alloys, manual controls, and on goes the list.

|

|

Courtesy Cape Horn |

|

A Cape Horn unit mounted on a Beneteau First 38. |

Knöös announced his latest design, the Sailomat 800, an updated version of the 760, will be released this fall.

“The overall features of the Sailomat 800 are similar to the 760, with less weight and a more efficient and lighter servo blade,” explained Knöös. “Overall performance is improved, mounting is very simple, and it’s priced about the same as model 760. And naturally, the 800 is covered by a U.S. patent.”

The 760 and 800 both feature a polycarbonate airvane, lightweight marine aluminum construction and an adjustable, easy-to-remove base mount that fits any transom angle and requires no mounting tubes.

Knöös makes his home in sunny southern California, but continues to manufacture the Sailomat in his native Sweden. While he still manages the daily business operations, he is now looking for a “partnership in marketing and sales,” allowing him the opportunity to focus “solely on the innovation and engineering side.”

If you have seen only three vane gears in your entire life, one of them was probably a Monitor servo-pendulum, built by Hans Bernwall and design director Ron Geick at Scanmar International near San Francisco. Their market presence has grown from many years of producing a simple, strong, straightforward servo-pendulum design.

Sturdy silicon bronze bevel gears once served as the heart of the Monitor’s servo mechanism, joining the push rod with the servo blade. That was until Geick noticed that a prototype set of precision-molded stainless steel gears, with their tighter granular structure, moved more smoothly and were less prone to wear than the bronze gears. The Monitor’s first batch of stainless gears also revealed another advantage: they required no touch-up machining, allowing faster assembly and less delay for eager customers.

The Monitor’s mounting structure also has taken off in a new direction in recent years as new transom shapes demand ever-more creative wind vane mounting concepts. While the Monitor’s underlying design and construction have remained fairly constant since it entered production in the late 1970s, the Swing-Gate, pioneered by Geick in 1999 for Tony and Mitsuyo Williams’ Catalina 42 Windriver, for the first time enabled crew to open the Monitor like a door over a sugar scoop transom, permitting use of the swim ladder.

Marilu and I tried out Windriver’s Swing-Gate when we went for a swim in the anchorage at Tahuata in the Marquesas. The Swing-Gate opened smoothly and easily, with no play in the finely-fitted stainless tubing.

“We designed a newer version of the Swing-Gate for boats with a solid reverse-slope transom with a central drop-down ladder about a year and a half ago,” Geick explained. Not long after this engineering achievement, another customer walked into the shop asking for a Monitor to fit an Outbound 40.

“The boat transom was configured so neither the vertical nor the sloped Swing-Gate mount would work,” Geick continued. “We built a hybrid sloped version that keeps the ladder clear and accessible — it will fit only an Outbound 40. We have an extra set of brackets built and ready for the next Outbound 40 customer who walks through the door.”

In the unlikely event of needing a replacement part for your Monitor, Bernwall has a well-established reputation for his zealous adherence to Scanmar’s warranty policy. No matter where you are in the world, if your little coral island in the South Pacific has a loading dock or a landing strip, he will send warranty replacement parts to get you back under sail in the shortest time possible.

When 16-year-old Jessica Watson sailed out of Mooloolaba Harbor, Queensland, Australia, on her record round-the-world sail aboard the Sparkman & Stephens 34 Ella’s Pink Lady, she turned the helm over to a Fleming Global Équipe servo-pendulum, which is now manufactured exclusively in Australia. Through good weather and bad, including several knock-downs in 75-knot monster gales in the Southern Ocean, the Fleming vane, constructed of super duplex stainless castings, faithfully kept Pink Lady on course.

One piece of equipment you will see more of in cruiser anchorages these days is a vane gear combining the classic appeal of a varnished hardwood servo blade with a high-tech mix of virtually indestructible marine-grade components.

Light, sleek and attractive, Voyager Windvanes of Cambridge, Ontario, Canada, builds a servo-pendulum self-steerer of Tenzaloy 713 aluminum-zinc-magnesium castings, which offer a high strength-to-weight ratio along with superior resistance to oxidation in a marine environment. The servo shaft and vane mast feature “indestructible bearings and Teflon bushings” and fast, easy response in light airs.

When the wind starts howling, rather than leaning over the stern to switch to a storm airvane, you simply adjust the counterweight to accommodate the increased wind strength.

Voyager’s innovative wheel drum steering adaptor is “activated by a Kevlar belt,” explained company spokesman Gordon Laco. He added, “The drum is infinitely adjustable and is locked by a brake disc design.”

Most installations of Voyager units weigh in at anywhere from 40 to 55 pounds, significantly less than most of its competitors and certainly an advantage on vessels of less than 35 feet LOA. The 12-inch by six-inch mounting footprint with only four mounting bolts eliminates mounting poles and leaves more room for a swim ladder or an outboard motor davit.

Under new ownership by Phil George, the new Fleming Global Équipe series took Kevin Fleming’s original Global series to its next logical step with worm-gear vane mast control, a 35 percent increase in strength-to-weight ratio and a polymer airvane that replaced the former plywood foil.

The Global Auxiliary Rudder, reminiscent of the Sailomat 3040 and the Windpilot Pacific Plus built by Peter Förthmann in Hamburg, Germany, is completely new to the Fleming line. The Global Auxiliary Rudder is a totally self-contained steering system comprised of both a servo blade and an auxiliary rudder. Like all auxiliary rudder systems, the system doubles as an emergency rudder in the event of main steering failure.

The granddad of all modern servo-pendulums is of course the venerable Aries, designed by Nick Franklin and introduced to the world in the 1968 Sunday Times Golden Globe Race. “The Aries is hard to improve,” said Peter Matthiesen, who bought the company in 1992. “Nick always tried and in the end he ended up with the old Aries standard design as the best and most reliable one.”

Matthiesen’s main challenge has been in coping with the latest sugar scoop and reverse transoms with swim steps, a familiar story among vane gear builders. But as for the Aries itself, Matthiesen said in a recent e-mail, “No, I did not change it. The sea did not change, and the boats are still steered by tiller or wheel.”

Another servo-pendulum model is the Cap Horn self-steering gear developed by Canadian circumnavigator Yves Gélinas. The CapeHorn concept uses a single tube that is installed through the boat’s transom. This tube carries enclosed control lines that are connected directly to the boat’s steering quadrant. This approach eliminates exterior steering lines, making for a less cluttered cockpit. And, according to Gélinas, the CapeHorn approach leads to a lighter, less expensive and less obtrusive installation. Gélinas tested his CapeHorn concept himself by sailing a 28,000-mile circumnavigation in the early 1980s with his CapeHorn unit doing all the steering.

Trim tab auxiliary rudders

Imagine a trim tab auxiliary rudder dutifully steering a 35-foot vessel while its airvane is mounted at the top and off to one side of a solar panel arch. Scanmar’s Auto-Helm has always been capable of such unorthodox installation, yet skippers are getting more creative at pushing the envelope in finding places to mount the airvane.

As long as the connecting cables, similar to bicycle brake cables, are not kinked between the upper and lower units, you can install the airvane mast literally anywhere there is uninterrupted wind current to the airvane.

Scanmar appears to be the sole survivor of all the trim tab builders that have come and gone over the years, more than likely because of its uniquely adaptable installation. There are plenty of online designs for building your own trim tab and auxiliary rudder, but you would be far better off taking all that time and money spent on machining and refining your self-steerer and investing it in a more redeeming pastime — like ocean voyaging!

Bernwall will be the first to tell you: if you think your vessel really needs an Auto-Helm, he will be more than happy to sell you one, but he will still recommend the Monitor first. Remember, while a trim tab feathers more delicately while sailing downwind in light airs, in rougher conditions it does little more than offer some stationary lateral resistance to prevent yaw. The servo-pendulum, on the other hand, actively repels side-sliding, keeping your boat in the groove while surfing down the faces of huge waves.

Airvane-controlled auxiliary rudder

For over three decades, each self-contained Hydrovane auxiliary rudder unit was built entirely by hand. With a growing customer base, though, John Curry decided to transform the shop in Nottingham, England, into a modern factory and use computerized CNC machines.

|

|

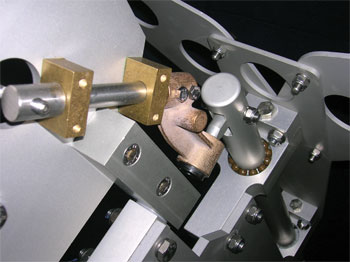

Courtesy Sailomat |

|

Close-up of Sailomat unit shows finely-made parts and a clever mechanism for steering the boat using the wind. |

After streamlining production, Curry set his sights on beefing up the Hydrovane’s strength and overall performance. “It is no secret that the average boat size is growing in both length and breadth,” Curry pointed out. “We set out to increase the power and performance of the Hydrovane. The first project was the rudder. The size of the rudder determines the steering power of the equipment. Initially, we thought that would be easy enough, simply make it bigger. Well, we learned there was more to it.”

Besides having to make a new 550-pound rudder mold, he found that as the rudder got larger, the complex hydrodynamics around the rudder surface also changed. “We had to learn more about the balance of the rudder,” Curry explained. “There is an optimal placement for the shaft hole. If it is too far forward, the rudder is hard to turn. Conversely, by progressively moving the hole aft, there is a point when the rudder goes wonky — no longer knows which direction is forward.”

With the aid of an engineering student from the University of Southampton Engineering Department and access to the university’s test tank, Curry’s team finally determined the right rudder balance and moved on to designing a stronger rudder shaft and bearings, along with improvements to the Hydrovane’s internal gearing.

Diminished true wind speeds on ever-faster boats in downwind sailing are placing a new kind of demand on wind vane self-steering systems. Some boats can achieve six knots on a run in less than 10 knots of true wind, leaving only three or four knots of true wind for the airvane. “All self-steering systems have no problems performing in heavy weather,” Curry pointed out. “That is when their source of power (boat speed for servo systems and wind speed for the Hydrovane) is always more than needed.”

Hydrovane’s answer to the need for more downwind steering power is a new extended airvane, now in the final design stage. Hydrovane also offers a new shortened Stubby Vane, equal in power to the regular vane, to accommodate arches for solar panels.

Whatever your cruising plans may be, a wind vane self-steering system should be an integral component of your ship’s rigging. There is a wind vane self-steering product to accommodate every type of deck layout, transom configuration and main steering.

———–

Bill Morris completed a circumnavigation, two-thirds singlehanded, via the Suez and Panama canals aboard his 1966 Cal 30 Saltaire. He is the author of The Windvane Self-Steering Handbook, published by International Marine.