[gtx_gallery]

Editor’s note: The following is an excerpt from J.R. Williams’ upcoming book on his sailing adventures, Tales of A Blue Water Cruiser.

In the first few days of January 1999, I was busy getting my 59-foot steel ketch Havaiki ready for my first passage from Honolulu to Papeete in Tahiti. I discovered that the boat was close to being dismasted as it sat at the dock! We found one of the drawbacks of wooden masts. Even after fixing that issue, we still almost lost the mast while en route to Tahiti. Both times I was lucky indeed.

The Good Lord was looking after us on the Friday morning when I cranked my friend Mike up the mainmast so he could begin sanding the wooden stick. All went well until he got down to the lower spreader. To my surprise and consternation, he yelled down to me that he had found dry rot in the mast on the starboard side. Thankfully, we found it at that mooring instead of at sea when a mast failure would have been disastrous.

When Havaiki’s builder, Samuel Kerr Robinson (see sidebar) constructed the yacht, he designed it to go through the canals in Europe. To accomplish that, he built it with a shallow six-foot draft and with its wooden masts on tabernacles so they could be lowered fairly easily to go under the low bridges. To aid in lowering the masts, Robinson had two long, aluminum running poles that would act as a tripod to spread the weight as the mast came down.

Since the masts were heavy with plenty of inertia once they got going, I read and reread the mast-lowering instructions that Robinson had written up to make sure I understood how his system worked. Then I worked diligently to get everything set up properly. I had three friends to help me and after finally getting the base of the mast out of the tabernacle, the mainmast finally began coming down properly.

When the mainmast was almost down, however, the starboard running pole broke (due to interior corrosion), the mast swung to port, and, with a sickening crack, it broke at the dry rot at the lower spreader. Luckily, it missed hitting me or any of my helpers. It came within six inches of hitting a cruising fishing yacht, Babe, that was tied up outside Havaiki.

Everyone came running to help us as the mizzen was bent at a terrible angle, as was the roller furling. My friend Lynn got in the dingy, and while Jas, Andy and Don helped hold the roller assembly up in the air to ease the bend in it, Lynn was able to drive the pin out of the upper tang, and we got the roller furling off and onto the pier. Then we eased the strain on the genoa winch, which enabled us to get the mainmast up on top of the concrete piling. The owner of Babe helped us by maneuvering his boat around so that we were able to straighten out the mizzen. His deck was too low to help with the main and as we were afraid of hurting something or somebody, I elected not to do anything for a while. With everyone’s help, we finally got the main slid over onto Havaiki.

My friend Larry came by on Tuesday and suggested that we talk to Gary Brookins about doing the work on the masts. Brookins came by the club after lunch and decided he would have no trouble making new masts for us. We also found some dry rot in some of the spreaders. I spent the rest of the afternoon removing all of the rigging so the mast was ready to take off the boat.

I decided to redo all of the electrics on the masts and to run all of the wires inside the masts to keep them out of the sun and the weather. The estimate on the mainmast was $12,500 and another $8,000 for the mizzen. With the dry dock, rigging and painting, the bill would come out to be around $35,000.00. I said to go ahead, and the work on the new masts began.

I stopped by when the masts were getting ready to be glued and discovered they were going to put the radar hole in conjunction with the SSB which would end up being 18” too high, so we got that straightened out.

The new masts were finished and installed. After a host of other jobs large and small and a complete provisioning, we were ready.

Heading for Tahiti

We finally left the slip and got underway about 1145 and spent 45 minutes calibrating the compasses. We turned and went out the pass and had nice winds for about two hours. They kept petering out until they finally went flat, so we began powering. At 2300 it was too overcast to see much of the moon.

For the next seven days, we sailed to the southwest. I had to deal with issues involving the engine transmission and fixing a faulty genset exhaust. We also lost our VHF antenna in the 15- to 20-knot winds. These were all minor issues, however, compared to the real problem that cropped up seven days into the passage.

I’m going to quote Havaiki’s log: “Just got down from the mast – can’t believe it! Slept pretty soundly last night and got up at 0530. About 0845, as I was getting the weather fax broadcast, I heard a banging sound on deck, and when I looked, the starboard intermediate shroud and running back were on the deck.”

I secured the rigging sections and then had the biggest stroke of luck: the nut that had worked its way off the bolt that held the intermediate shroud in place had amazingly fallen straight down and was lying on the deck.

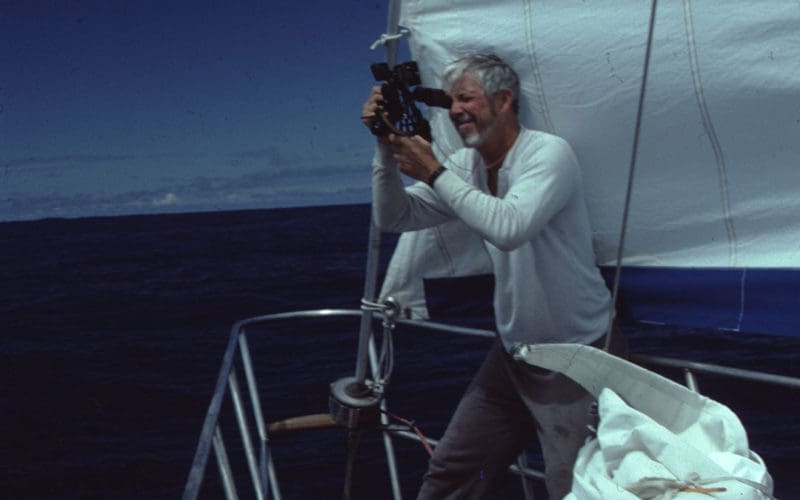

I grabbed some tools and after lowering the mainsail, my wife Jas helped me ascend the mast. Fortunately, we were becalmed at the time, and all I had to put up with was the rolling of the boat. It’s hard to believe how much the top of the mast wanders around without both intermediate shrouds to stiffen it. Anyway, I had a hard time keeping the bolt through the mast and myself attached. Every time the boat would roll, the bolt would pull back through the mast. It took about an hour, but I was finally able to get everything secured.

Best time for a rig problem

It was one of those experiences I have never forgotten. I thank the Lord that the nut came off while we were becalmed, under power, and in fairly flat seas. If it had happened a day or two before, while we were driving into heavy seas, the nut would have gone over the side and we would have had a lot of problems. As it was, in the last-minute rush to get everything together and underway, one of us –– and the blame lies solely on me –– neglected to double-check the fitting. As has happened so many times both before and after, God was looking out for me and guiding my path.

A few days of sailing later, we were only about 20 miles from Mataiva, and we were lifted enough during the night that it was obvious we would pass east of Tetiaroa. We were surrounded by birds when I went on deck about 0700. They appeared to be boobies and shearwaters, so we were definitely near land.

We passed Mataiva around noon and were close enough to see the small village on the west side. It ended up being another beautiful night and by 1930 we were only 120 miles from Papeete. In the log I wrote: “Can’t believe that 27 years have passed since I was in these waters the first time”.

We had a beautiful sunrise on Monday morning, and we sailed slowly most of the day. The wind finally went around to the NE at 5 to 10 knots, so I dropped the sails and began powering about 1500. At 2326 the log reveals; “Well, we’re on the pier in Papeete. The place is really jammed. I don’t know if Gerard will let us squeeze in…Two young people from New Zealand helped us tie up here. Tomorrow we’ll find out if we can stay on the quay somewhere. For now, I’m having a Scotch.”.

Two strokes of luck: finding the dry rot in the mainmast at the dock before leaving Honolulu and then discovering the loose shroud while becalmed and the nut sitting on deck waiting to be picked up. They saved us from what could have been disaster at sea. n

J.R. Williams, a retired airline pilot who worked for Hawaiian Airlines for 31 years, is an experienced Pacific sailor, ham radio operator, and lifelong race car driver in stock cars and midgets. He’s based in Carson City, Nev.