Fishermen boat and boaters fish, that seems to be a given worldwide. Boating and fishing go hand in hand. People fish everywhere, and most cruisers have their own gear on board. Even our 35-foot catamaran Irie came with an old fishing rod when we bought her. How hard could it be? My husband, Mark, learned from another sailor how to open conch shells and remove and clean the ugly creatures inside to make delectable conch fritters, but our fishing success had been pathetic. We learned, however, like so many things, practice makes perfect.

Our first lesson about fishing techniques happened in the cute town of Solomons Island, somewhere in the Chesapeake Bay. Mark and I were walking our dogs along the boardwalk when we spotted a “Tackle and Bait” sign. After dodging a plethora of crab pots and hearing that the trapped animals thrived in these waters, we wanted to buy a tool and catch a few. Maybe a net? Wasn’t that what the kids used off the piers in Edgewater Marina where we prepped our boat for the journey south?

When Mark discovered the only good way to catch crabs is with one of those heavy cages, we gave up on the idea. How about catching fish? I remained outside with our pups, while Mark returned to the store to inquire about fishing.

“What did you find out?” I asked when he reappeared on the boardwalk.

“Nothing!”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, this guy rambled on about all kinds of things, like spoons and lures, pointing out colorful items on display. When to use what, and why, and where, and how. As if he was talking Chinese. I didn’t understand what he was trying to explain. Sorry.”

|

|

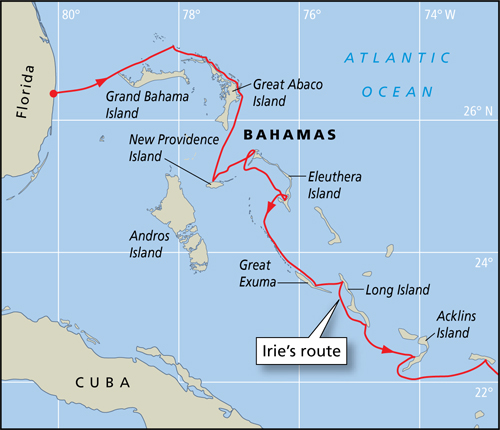

Liesbet and Mark began learning their fishing skills during their time voyaging in the Bahamas. |

Oh well, there were plenty of grocery stores around, and meat hit the spot as well. Plus, on the Intracoastal Waterway, fishing didn’t seem appealing anyway. We forgot about catching our own food until Stuart, Fla., where we made the last preparations for our trip to the islands together with a bunch of other cruisers.

“So, you’re heading to the Bahamas, eh?” one of them asked. He must have been Canadian.

“Yep.” Wasn’t everybody?

“The fishing is awesome over there! You should get a spear or a Bahamian sling. And don’t forget a trolling line,” the old-timer recommended.

“Alright,” I said. What the heck is a Bahamian sling? How do you even use one?

“Let’s go online to check what those things look like and how they work,” Mark suggested. A visit to Walmart later, we were the proud owners of colorful lures, a small fishing kit, a flimsy blue net, a cheap rod and two spools of line — no Bahamian sling. Too advanced. Mark bought extra hooks at a hardware store, and I ordered the Fishing for Dummies book on Amazon. We also obtained a funky green light to attract our victims, or study them, at night. We were ready.

|

|

Buying fish from the pros is always easier. |

Trolling in Bahamian waters

Once in the Bahamas, we trolled one line during slow sailing trips. At anchor, Mark used the rod or hung a thicker handline from a cleat. Nothing ever happened.

Sailing between Marsh Harbour and Great Guana Cay in the Abaco Islands, we trolled the heavier line and tied the fishing rod to the stern of the catamaran on the other side, doubling our chances. Michael and Sabine, friends from a previous RV trip, were visiting from Germany. Wouldn’t it be great to serve these world travelers freshly caught fish for dinner?

“Oh no! Liesbet, slow the boat down. We have a problem!” Mark’s voice bellowed from the stern.

“Michael, can you grab the Lifesling? Yeah, that yellow thing in the bag over there. Take it out and throw it overboard. Don’t worry, it’s attached.” Mark gave us rapid commands. Should I turn the engines on?

Splash! Without further ado, my husband was in the water with a mask and knife. No engines. Good idea. Both fishing lines were tangled. Around each other and the rudder — the result of our maneuvering to get settled for lunch. We had forgotten about the lines. Mark managed to get one line free, but the hand-line was wrapped around the propeller as well. Grumbling aloud, our captain cut the line. There went $30 of equipment.

“At least we finally managed to catch something. Our boat!” I chirped, when my husband was safely back on board. Clearly, fishing wasn’t one of our talents. We continued purchasing seafood from locals.

Once in Nassau, we bought a long, sturdy trolling line — 300 yards of it. On the crossing to the Exumas, Mark decided to try it out. From the moment he took the plastic wrapper off the coiled fishing line, the contents exploded, leaving a tangled mess on his lap.

|

|

Fishermen in the U.S. Intracoastal Waterway. |

“Give it to me, sweetie,” I offered. “I have more patience than you, and six hours should be enough to untangle it and wrap it neatly around a spool. There’s not much else to do on this trip.” Two hours later, the job was done. We let the line out its full length. It was long. Too long.

“Let’s cut it in half,” I suggested.

“You sure? It’s a brand-new line … how do we know what’s half?” Mark asked.

“We roll it onto another spool and count the wraps. Then, we wind it again on the first spool and stop when we’re at half the count.”

Fifteen minutes later, the task was completed and we put one of the lines to good use. All we caught was seaweed. Twenty times of pulling the line back in, removing the slimy greens and letting it back out was frustrating enough to give up for the rest of the passage. Mark didn’t like my suggestion of making seaweed soup.

Other cruisers catch plenty

Conversations with other cruisers explained the problem: us. Everybody else caught plenty of fish. One woman mentioned that they fed the mahi-mahi they reeled in to their dogs and kept the “better tasting” wahoo for themselves.

Warderick Wells in the Exumas is a fantastic destination. Big, perfect-for-the-pan-looking fish circle your boat. Succulent lobsters chase each other on the ocean floor in plain view. It’s intriguing and infuriating at the same time because Warderick Wells is part of the Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park. Everything is protected, so there’s no fishing allowed. That’s the reason why snorkeling is incredible there. A side benefit from all the rules, though, is that you can learn about tasty animals’ behavior for future reference.

|

|

Liesbet enjoying the beach with Irie anchored in the Land and Sea Park of Warderick Wells in the Exuma Cays. |

What better place to try our fishing light one night and watch the show? The battery holder broke, so we put the one from Mark’s headlight in it. Then, we tied our favorite cooking pot to the bottom of the light to hold it down in the water. I’m not sure why the light wasn’t heavier or it didn’t come with its own weight. Bad design. Luckily, Mark knows how to tie knots. A bowline always works, even after a few drinks.

“You know, one of these days I’m going to lose it all,” he jokingly said, lowering the contraption. As if on cue, it happened. “Oh no, I just did. The knot untied. Everything is sinking to the bottom!” A tipsy giggle followed.

“Is it at least attracting beautiful fish?” I wanted to know, as I peeked over the side and watched the lit-up pot approach the ocean floor. It’s better not to think about losses like that for too long. I took count: a pot, a new light and part of the very important headlamp. We couldn’t afford losing any of it. Off went my clothes. A jump into the cool, dark water followed. The dogs thought I fell overboard and barked frantically. Fortunately, there were no neighbors. Hopefully no sharks either. I should have thought about this plan a little longer.

“Can you hand me a mask? And fins!” I screamed from the water surface. Yes, I should have given this more thought. The bright green light was easy to spot — 15 feet isn’t that deep. The water actually felt good, and the stars sparkled above. Romantic.

“Mark, you should come in as well,” I suggested. “This is cool.”

“Can you just get the light, please?” my oh-so-romantic other half responded.

Minutes later, I handed him his precious fishing light. He was happy. So happy, he didn’t even thank me, or get me a towel. But I learned an important lesson: Cocktails aren’t just tasty, they help you make decisions hastily.

|

|

Mark learning the ropes about taking the meat out of the conch shell from a sailing friend in Hope Town, Bahamas. |

Still no luck

After being in the Bahamas for more than three months, Mark and I still hadn’t caught a fish. What were we doing wrong? One evening, we sat in our cockpit for dinner. We’d run back and forth to George Town multiple times to get water and other provisions. We were tired. Mark was finishing the last pork chop and contemplated eating the final baked potato as well. I had potato skin (Belgians don’t eat the skin) and pork fat (no fat, either) left on my plate and threw a piece overboard.

“Wow, look at that! Some fish are eating the scraps. Big ones! Get your gear, baby. They like pork!”

“Hand me that piece,” Mark requested, after getting his line and hook ready. He put the bait on the hook and threw the line overboard. Within seconds, a fish grabbed it. Mark lifted the animal out of the water, but it escaped. Huh? The commotion startled the other finned creatures. I threw more pig fat in the water to change their minds and lure them back.

“Let’s try again,” I suggested.

“We’re out of pork,” Mark replied.

“How about potato? This one is undercooked. Easy to hook.” I handed Mark a sturdy piece of starch.

“Fish don’t eat potato. Grab the net just in case.” Mark hung the line off the boat again. This time with a chunk of baked potato.

|

|

Mark and Liesbet catch their first fish, a horse-eye jack. |

“We got one! Get the net! Get the net! Quick, get it in the net!” he screamed after three seconds.

“I’m trying. It’s huge and looks heavy.” What do I know about catching fish? With or without a net?

We trapped it in the webbing and held its body against the transom steps. The fish wriggled so much that it wrapped itself around the material. We didn’t know what to do. So we both pressed the net and its contents against the steps, and sat there. Thinking. After a few moments, I let go, grabbed the bottle of rum and poured liquid in the bouncing gills. The fish kept moving. I tried vodka. We loved our rum and Cokes too much. The fish struggled and refused to die. I didn’t like this at all. When our catch finally calmed down, we put it in a bucket. It didn’t quite fit. Each time I stepped over the bucket, now in the cockpit, its tail jerked and startled me. He was still alive and kicking! We would need to find a better, quicker way to kill a fish if we ever succeeded in catching one again.

Half an hour later, the fish didn’t budge anymore. We stretched it on the floor of the cockpit. Pretty big.

“Now what?” Mark asked. It was 9 p.m. and dark.

“Can we call anybody on the VHF for help?”

“Not really.” It was late and we’d sound like idiots.

|

|

Mark cooking Irie’s first freshly caught fish on board. |

“What kind of a fish is this? I sure hope we can eat it, so it didn’t die in vain,” I said, sadness growing.

I checked our pocket guide, Corals and Fishes of Florida, the Bahamas and the Caribbean, and deduced it to be a horse-eye jack.

“They don’t exceed 3 feet,” I read, but it was followed by an asterisk: “Large specimens of jacks may be poisonous to eat.” Hmm. We measured the fish: 2 feet. “Large specimens” had to mean closer to 3 feet. I took photos; Mark cut the head off, gutted the body and stored our meal in the fridge. It barely fit, but we couldn’t remove the tail. We needed a sharper fish knife. Still ill-prepared to be fisher(wo)men.

The following evening, we invited friends over for our first home-caught, home-cooked fish dinner. It wasn’t the best fish in the world, but at least we finally retrieved something. And nobody died.

Liesbet Collaert and her husband, Mark, voyaged on their cat Irie. Liesbet is writing a book about their experiences sailing in the tropics.