Imagine waking up in the middle of the night and finding your spouse, partner or friend unconscious. Now add that you are 35 nautical miles offshore, plus another 74 miles from the closest town with a hospital in a foreign country.

This is the situation I found myself in with my husband, Rich, on March 10, 2016, off the coast of Brazil. As cruisers venture away from the shores of the U.S. and too far out of cellphone range to call 911, dealing with life-threatening medical emergencies becomes more problematic. I believe that a combination of medical equipment, onboard technology (like DSC VHF and AIS) and my ability to use those tools were critical to my husband’s survival. It is one thing to have all of these items on board; it is another to use them effectively when you are alone and the person is dying before your eyes.

Rich and I have been cruising for more than 15 years on Windarra, a Stevens 47. In November of 2015, we were along the east coast of South America. By March, we had left Vitoria, Brazil, with two more stops planned before the 2,200-nm passage to Trinidad.

Rich has heart disease. In 1992, at the young age of 47, he had a myocardial infarction (MI) and a subsequent triple bypass despite watching his weight, exercising and maintaining a healthy diet. Medications have helped to keep his heart issues under control since then. In 2012, while we were in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, he had another MI. After a week stay in a private hospital, we returned to Seattle, where his cardiologist placed a stent in one of the earlier bypasses from 1992. Rich was cautioned that he was at risk for ventricular defibrillation in the future due to the scar tissue on his heart from the two MIs. At this point we decided to buy a home version of an automated external defibrillator (AED) to have on board for an emergency. Both Rich and I were trained to administer cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and to use an AED when we worked at Boeing. Like most emergency equipment we carry on board, we had hoped we would never need to use it.

|

|

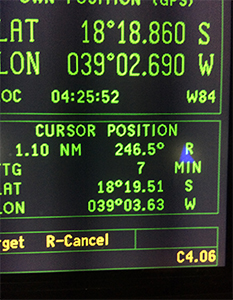

Windarra’s lat/long position when Rich collapsed. |

|

Elaine Cashar |

Over the many years of passages as a couple, we have long established habits. While on passage, Rich and I are both in the cockpit. The center cockpit of the Stevens 47 is large enough for one person to lie down fully and sleep while the other person is on watch. Both of us feel comfortable with boat and sail handling, navigation and electronics. We don’t have pink and blue jobs but more primary and secondary jobs. I have to admit that Rich has more experience at the helm.

Something wasn’t right

At midnight on March 10, 2016, Rich was on watch and I was asleep. He woke me and asked me to watch, while he went below to switch over the fuel pre-filters. Rich was concerned that the filter was clogging since we were motorsailing. After he made the switch and felt comfortable with the new arrangement, he went back on watch and I went to sleep. I can’t say for sure what woke me up around 0200, but something was not right. I called to Rich but no answer. His breathing was raspy and uneven. I tapped on his shoulder and tried to wake him up, but he was unresponsive and I could not find a pulse. This was the nightmare situation that we had talked about but hoped would never happen. Immediately I went below and got the AED, lifted his t-shirt and placed the pads on his chest per the diagram on the AED. The Philips HeartStart Home AED provides audio instructions to help you through the process. I waited while it analyzed Rich’s heartbeat. The device announced that a shock was necessary, so I pushed the shock button. Rich moved slightly. Per the audio instructions, I started CPR until the next analysis cycle. No further shocks were necessary. Rich’s breathing became more regular and so was his pulse, but he was still unconscious.

I had to get Rich to a hospital.

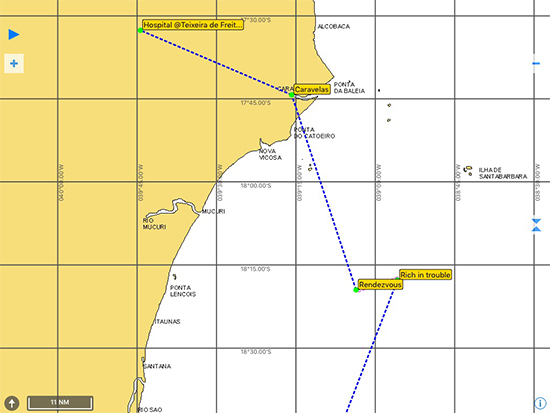

Even though we were offshore, I chose to use the digital selective calling (DSC) emergency feature of the VHF radio instead of the EPIRB and hoped that there was a ship nearby. Using the VHF microphone in the cockpit, I declared, “Mayday, mayday, medical emergency.” Luckily a Brazilian tugboat in the area responded in English! I was so glad to hear the captain’s voice. We have an automatic identification system (AIS) receiver and transmitter, so I could see an AIS symbol on the charter/plotter representing the tug. The captain could see a symbol representing Windarra on his display as well. We coordinated a rendezvous about five miles away.

|

|

Windarra’s position off the coast of Brazil. |

|

Elaine Cashar |

Preparing the rendezvous

Since Rich was incapacitated, it was my responsibility to prepare for the rendezvous. I furled the staysail and changed course to converge with MV Norsul Caravelas. Between checking on Rich and our position, I started to gather items for abandoning Windarra. We have a packed abandon-ship bag, but since we were not climbing into a life raft it did not seem appropriate. Instead I grabbed two backpacks and filled them with our iPhones, iPad, Iridium GO, charger cords, wallets, passports, Brazilian and U.S. currency, boat papers, Rich’s medical file and a few toiletries. I forgot to get any clothes or the boat’s laptop.

Around 0400, we rendezvoused with the tug. I brought Windarra alongside, the crew threw lines across and we secured our vessel to the tug. They brought across a stretcher and we slid it under Rich in the cockpit, secured him with multiple Velcro straps and lifted him over the lifelines and up to the stern deck of the tug. I let out the anchor. I don’t know how much chain since it was dark, but at least 100 feet. We were in 30 meters of water so I knew it would not touch bottom immediately. I shut down Windarra, tossed loose items from the cockpit down below, turned off all of the lights except the anchor light and locked the hatch. The crew let loose the lines and Windarra was cast adrift.

The captain contacted the Brazilian navy and medical facilities on shore. Several hours later, a smaller private vessel with large outboards and an EMT on board met the tug. We traveled up a shallow river to the village of Caravelas and a small clinic. Rich had his eyes open by this point but could not speak. When I asked him to blink if he heard me, he did not. He was able to move his arms and legs a little and his face was not slack on one side so I had hope that he had not suffered a stroke or another MI.

Once we got to shore, it was only a half-mile to the clinic and a quick ambulance ride. No one spoke English. Using my cellphone, I called the U.S. embassy and with their help communicated that we needed to go to a hospital with an intensive care unit (ICU) and a cardiologist. A nurse at the clinic administered much-needed oxygen to Rich and started an IV. Rich improved with the oxygen and he began to respond. He began to talk, focus on my voice and squeeze my hand. Later, Rich was even able to step into the ambulance for the 74-mile drive to the hospital in Teixeira de Freitas.

|

|

The Brazilian tug Norsul Caravelas rendezvoused with Windarra and took Rich and Elaine aboard. |

|

Vladimir Knyaz |

I could not have gotten Rich to a hospital in time without the AED, DSC and AIS.

The case for an AED

Having the AED on board along with prior training saved Rich’s life — there is no doubt about it. Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) occurs when the heart unexpectedly stops pumping blood through the body, which is typically caused by a disorganized heartbeat, or “ventricular fibrillation” (VF). By having an AED aboard, I was able to apply a shock as soon as I found Rich unresponsive. Without the AED, the outcome would have been tragic.

Not every cruiser should have an AED on board, but for someone with a medical condition like Rich, having an AED is wise. In hindsight, I wish we had had oxygen as well. The need for an AED is not limited to the older population. There have been cases where young people — especially student athletes — suddenly collapse, never knowing that they had a heart issue. Consider a cardiovascular exam for all crewmembers.

The DSC allowed me to broadcast the mayday and alert all of the vessels in the area at once. Since we were closer to the Brazilian coast, it made more sense to make contact locally. I used the DSC feature of the VHF to do this, as opposed to using an EPIRB. Our boat’s GPS is wired to the VHF, so our location was also transmitted when I pushed the emergency DSC button. When the captain of MV Norsul Caravelas responded, we were able to communicate on a specific channel without having to query and negotiate for a communication channel, which also saved valuable time.

|

|

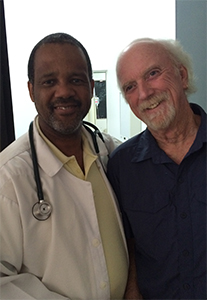

Rich with one of the Brazilian medical staff. |

|

Elaine Cashar |

The AIS allowed the captain and me to coordinate a rendezvous and to make sure we were both on track. The captain could see where Windarra was on his navigation system, just as I was able to see the symbol representing his vessel on our charter/plotter in real time. I was able to set the autopilot and verify my course to intercept and prepare for the rendezvous with assurance that we would not miss each other.

Rich spent seven days recovering in the hospital. We then flew home to Seattle and seven days later he had an internal defibrillator and pacemaker implanted. He has made a full recovery and we plan to continue cruising in the near future. Windarra was recovered by the Brazilian navy and brought to Caravelas.

Elaine Cashar and her husband Rich Jablonski cruised aboard their Stevens 47 Windarra from 2001 to 2016.