On my way out of the door to join my two shipmates in Las Palmas, Canary Islands, for a trans-Atlantic passage, I ripped out the November page of the North Atlantic Pilot Chart. The chart clearly showed that 70 percent of the time the wind blew from the northeast or east-northeast, and only 1 percent of the time were there calm conditions. Translation: We would have wind —and from the right direction — and a becalming was a remote 100-to-1 shot. Also, there was a long-standing sailing plan for this voyage (think Christopher Columbus), with no Gulf Stream or other testing obstacles. The upshot? Let’s not overthink this thing. Like they say in the islands, let’s go “dat way, mon.”

The assumptions

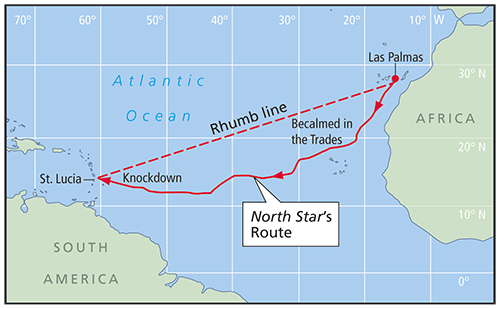

Here’s what we assumed we knew going into the voyage. Pilot charts are a good indicator of what will likely happen on a given voyage, and at its core, Las Palmas to the Caribbean is a simple trip governed by simple truths. There is a classic route, which we would take, sailing southwest to reach the trade winds and then hanging a right for St. Lucia (our destination). The trade winds would blow — because that’s what they do and have done for centuries to earn their name, and we certainly would not be becalmed. There would be no need for radical course deviations, and certainly no need to be significantly south of St. Lucia’s latitude (14° N).

And now I write these words after a very surprising trans-Atlantic crossing during which I came to recognize the following:

- I should have burned the November pilot chart rather than take it along. Nothing it said had validity for our voyage.

- Las Palmas to St. Lucia is not so simple; it may, in fact, require a most convoluted course.

- The trade winds may stop, for nothing in this ocean world is constant.

- That 100-to-1 bet? You should take those odds, for you will be becalmed and more than once.

- The route you take will be anything but “classic.”

- You will learn to love the sailing at 12° N, well south of your destination.

|

|

North Star crew in Las Palmas; from left, Rick Meisner, Ted Rice and Henry DiPietro. |

|

Birute Juodeniene |

I always try to ask myself after a major voyage, “What’s the lesson? What have you learned?” Well, how about this: If you want to look smart, keep your mouth shut and sail the conditions presented. If you are determined to look like a meathead, go ahead and make a host of assumptions about a voyage yet to happen.

Now here’s the story.

The scene

Las Palmas and the World Cruising Club host arguably the most exciting and well-attended sailboat rally in the world, the Atlantic Rally for Cruisers (ARC), first envisioned by Jimmy Cornell. Now in its 33rd year, and with more than 200 boats of all nationalities, makes, sizes and experience, the weeks preceding the rally see a steady influx of boats and crew, all with one key intent — to sail across the Atlantic Ocean. The fact that the rally ends on a gorgeous Windward Island in the Caribbean just before Christmas makes for exciting and exotic holiday prospects. There is tremendous organization to this event, including all manner of seminars, weather briefings, safety inspections and parties, parties, parties. The waterfront becomes transformed into a beehive of frantic boat and crew preparations.

Arriving in the last week before the start, we enjoyed the dockside adrenaline, but for me and my mates it was all about making a trans-Atlantic passage with close friends that I’d sailed with for years. Our skipper was Ted Rice, the owner of North Star, a stout, seaworthy 1983 Shannon 38 pilothouse cruiser. Ted is the third owner of the boat and has worked hard to improve and update all her systems. But no change was necessary to North Star’s solid, overbuilt, seakindly nature. She was designed for long-distance ocean sailing, pure and simple. Ted has come to know his boat like a book, down to every bolt and hose. He is an affable yet serious man, befitting his U.S. Navy career as a ballistic sub captain. Ted had sailed North Star across in 2014 with the help of Henry DiPietro, a fine and experienced ocean sailor with an infectious laugh who brings a wealth of creativity and good spirits to any boat he’s on. Both Ted and Henry have joined me for voyages on WildHorse, my Valiant 42 cutter, so we know each other’s moves and complement each other’s skills. We get along, and boats like us.

The start

The parade of 183 boats to the starting line on Nov. 19th was a mix of spectacular and manic. There were, in fact, two marching bands, and it seemed like all of Las Palmas had turned out to cheer on each boat. There is a natural squeeze point at the harbor entrance that demands single file and provides a fine spectator area that was overflowing. Outside the harbor, the start line was guarded by a large Spanish CG cutter, impossible to miss. All skippers had been advised against aggressive start tactics and seemed to comply. With nearly 3,000 nm to go, civility and good sense reigned (the ARC is a “rally,” but with a racing undertone. Times are taken, handicaps applied and there is an actual racing division. Cruising boats can race as well, and can use their engines with corresponding time deduction factors applied at the end in St. Lucia).

|

|

Becalmed in the trades north of the Cape Verde Islands. |

|

Rick Meisner |

So we were off — Sunday at 1300 in a light northeast breeze, all in good spirits with smartphones snapping and my GoPro recording. It was a grand and festive sight with 183 sailboats spreading their wings, all heading to the New World.

Soon, however, we were alone on a big sea, the other boats reduced to radar and AIS images. It had looked like the first 24 hours would allow us to gain our sea legs, boats and crews gradually adjusting to the rhythm of the sea. But that was not to be.

The first night

The first night just beat the hell out of us. We had been warned of an “acceleration zone” when heading south along the east side of the island. This zone had often spurred winds to twice their gradient strength, and it did so for North Star, turning a pleasant 15 knots into a mean-spirited 30-plus knots, along with a nasty 6- to 8-foot short period chop. Everything and everybody got tested at once — and it just would not quit. We kept reassuring each other, “It’s just the acceleration zone,” but it would not quit. The first major loss was our electric autopilot, and the next was our Auto-Helm wind vane, leaving us with mandatory hand-steering in a rainy, windy, bouncy mess. No one slept and we were left at dawn a cranky, salty, wounded crew cursing everything but ourselves. So much for gaining our sea legs.

The next surprise was how suddenly the wind departed — almost as if it had been sated with our pound of flesh and had crept back into its lair to sleep off its binge.

And so, we were left with no wind but also a very active seaway yet to settle down. What to do? Well, it was so early in the trip we knew we should just suck it up and wait for some wind (after all, it blows northeast most of the time, so why not just wait?). Then came a series of weather reports: There would be no wind, or spotty at best, until a good distance south and east of the Cape Verde Islands. It is fair to note there was a “northern route” option that some boats took that skirted a forecasted low and promised more initial wind. But it looked chancy to us and given that you needed to be fast to stay ahead of the front or face significant headwinds and heavy conditions, we decided that was not within our “polars.”

|

|

All systems shut down, North Star is becalmed. |

|

Henry DiPietro |

So after nearly two days of bobbing around with scant progress, one among us said, “You know, this is a rally, not a real race.” Within a few minutes of that subtle call to arms, our trusty Perkins diesel came to life and we pointed due south to “20/20” (20° N by 20° W). We were promised wind along that course closer to the African continent, and we did have it in fits and starts, engine off and sailing, engine back on, motorsailing.

Becalmed in the trades

When after a significant investment of fuel we thought it safe to turn west and find the trades, we did so — and ran smack dab into the most amazing, profound “Great Blue Windless Hole.” It was heartbreaking but it was also gorgeous: perfect weather for what looked like hundreds of miles, with not a ripple in the sea. Just an extraordinary zen-like, mid-ocean experience that brought us to another fateful decision.

We had learned from the ARC daily net that a number of boats were diverting to Mindelo in Cape Verde to refuel and carry out repairs. We could do the same and start anew, with our modest payload restored. But one of us boiled the decision down to its core: “Are we a sailboat, or not?” Well, when you put it that way!

We elected to shut everything down and enjoy the amazing conditions, rest up and wait for the wind. We were now a pure sailboat the rest of the way (more than 2,000 nm), with only enough fuel for twice-daily charging and a small emergency supply. By late on the second full day of our becalming, a breath of air steadied up from the east, followed by the trickling sound of North Star’s full keel on the move, and by morning we were under full sail heading west in what felt like the return of the trades. And now a rhumb line to St. Lucia? Wrong. Our breeze was the equivalent of fool’s gold, and soon revealed itself as an imposter.

|

|

North Star’s route through the less-than-steady northeast trades required them to sail farther south than expected. |

The weather

The weather itself was generally good, but the winds were quixotic and anything but the steady predictable winds expected. The trades were being deflated by a large trough to the north, strong enough to cut a windless swath along the traditional trade routes. We were in the middle of the prime area affected, and all traditional weather patterns had gone AWOL. The result was that any rhumb line sail to St. Lucia was hopeless. Instead, our own gribs, PredictWind and our daily weather advisor, Chris Parker from Marine Weather Center, were in agreement on a more tortuous path.

The issue now for North Star was that we had to sail; we could not just motor across a calm area to fetch wind. Yes, we had enough fuel for charging but not much more, and we were still on the fat side of 2,000 nm to go. When Chris Parker first said the most consistent, strongest wind was at 12° N, we all scoffed (St. Lucia lies at about 14° N). “No freakin’ way we sail 120 nm out of our way, then have to make up the same 120 on the return northward.” This attitude reigned for a day or so of measly westward progress before we succumbed. We picked up a SSE breeze that we could put on our port beam and rode the apparent air all the way down to 12° N — and there found five straight days of incredible hull-speed sailing, which meant 140 nm each 24 hours (big mileage for the 38-foot North Star). We were heading dead west and tearing a big chunk out of the course. Chris was right, as usual. Back north, another Big Blue Windless Hole was forming and we wanted no part of it as it moved westward and to the north of us. Against all odds and our initial doubts, we were happy to be sailing the hell out of 12° N.

But inevitably, those who go south of their destination must turn north, and so we did, reluctantly at 12° N by 53° W, and like someone slowly choking off a hose, the wind became spotty, then light, then nothing. Becalmed in the trades again! That 100-to-1 shot was sure haunting us.

We were still more than 400 nm SSE of the island and needed to move. We tried all our light-air tricks, but on 3 to 5 knots of air our stout vessel was virtually at rest. Our gribs showed east wind overtaking the area in a day or so. We groaned. Our previous becalming had been unique and enjoyable; this would be painful.

|

|

Ted Rice and Rick Meisner enjoy fast sailing at 12° N. |

|

Henry DiPietro |

Mr. Perkins to the rescue

Capt. Ted went off in a corner with his log, a sheet of graph paper and a calculator. After an hour or more of analysis, he announced we had enough fuel to motorsail 12 hours at 1,100 rpm, barely above idle, but yielding 3.5 knots. We targeted where the wind would first return, switched on and (slowly) got the hell out of there.

We and the wind arrived at the targeted coordinates together — a minor miracle. Out came the whisker pole to windward and out went the main to leeward and North Star picked up her skirts and took off at a steady 6 knots, right on course for St. Lucia, dead downwind on the ESE breeze. “Yeah!” I heard in a chorus of three. This was it for us, sailing straight for the barn.

The crash

We sailed true and fast for the next two days, closing in on St. Lucia Channel, where we would gybe our way down to Rodney Bay and the finish line for an estimated 0300 landing. The wind was fine and steady, but we could feel a clammy humidity in the air for the first time — “squally,” we called it. Then Chris Parker confirmed a greatly increased chance of squalls on approach to St. Lucia. We had discussed our squall tactics, especially as we were closing the coast with no moon; murky and hostile was the feel, dead black was the night.

The St. Lucia Channel is broad, but if you want to carve a coastal route, great care must be taken. On any east air at least one gybe must be taken to head down the west side of the island.

|

|

Henry DiPietro works the bow on a downwind run. |

|

Rick Meisner |

We had the best of intentions. We discussed squalls and our still-rigged whisker pole. We vowed two men in the cockpit at the first whiff of trouble, and all three of us on deck if any doubt. But good intentions are often defeated by something sinister and evil. A nasty, fast-moving squall overtook us with one man on deck. The result was calamitous.

We were knocked down by the second big gust, port cabin top and portlights in the water. A major miss on our part: Three portlights were open for ventilation and on the knockdown spewed ocean water like fire hoses. There was a malicious roaring sound as we struggled to gear up and slosh through several inches of seawater flooding the cabin sole.

If the scene was ugly below deck, it was our worst nightmare on deck. The whisker pole was out of control and clanging the forestay like it was determined to batter it down. The genoa, along with its sheets and foreguy were a tangled, torqued-up, volatile mess. The main, distended and prevented by two stout lines, was trying to gybe but could not. Our first reaction was to stare in wonder at the apocalyptic scene. The offending squall had departed as quickly as it came, but there were still 25-plus knots of gradient wind, enough to keep huge forces in the billowing canvas.

One of us crept low and slow along the starboard gunnel to the bow and found the pole downhaul had wrapped tightly around the bowsprit and was preventing any effort to furl the genoa. After clearing that tangle under god-awful conditions out on the bowsprit, the genoa still would not furl, and overhead the untethered whisker pole continued its assault. Overrides in the furler! With enough slack and by working the furler from a sitting position on the rail, the override broke free and we were able to furl the genoa, then drop and lash the pole. My God, it was a bad situation and left us with dry mouths and pounding hearts.

|

|

With laundry flying, North Star at the dock at Rodney Bay Marina in St. Lucia. |

|

Rick Meisner |

At some point, Capt. Ted had started the engine (fuel supply be damned) and, after triple-checking for any sheets in the water, put her in gear to regain our control and heading. By now we were nearly at our gybe point, and we waited patiently to execute a controlled maneuver so as not to overstress the rig.

The finish

So on full main alone we skirted Burgot Rocks, made the turn at Pigeon Island and crossed the ARC finish line at 0345 local. We had sailed nearly 3,200 nm on a 2,700-nm rhumb line course. We were exhausted but ebullient. The violence of the squall had left us chastised but whole, and with that strangely exhilarated.

Later, we slept the sleep of thankful men, knowing that we might have done better, but with full realization that we had done pretty damn well.

Rick Meisner, a retired exeutive, sails his Valiant 42 WildHorse out of Watch Hill, R.I.