Editor’s note: This installment of the newsletter is a companion piece to the Seamanship and Navigation newsletter of November 2021 that detailed a repair at sea of the clipper ship Cutty Sark. This time, Eric Forsyth looks at a feat of seamanship from the era of the last sailing merchant ships — an impressive foremast repair made by the captain and crew of the steel ship British Isles.

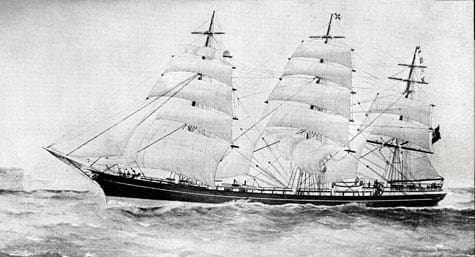

British Isles was a heavy ship, typical of the freight-carrying square riggers that ended the age of sail. She was built in Scotland and launched in 1884 with a registered tonnage of 2,287 tons and could carry 4,000 tons of cargo. The hull was steel, as were the lower masts and yards. The sheets and braces were chain or wire rope. When she left Wales in June of 1905 with a cargo of coal bound for Pisagua on the west coast of Chile, she was under the command of Captain James Barker and carried three officers, four apprentices, three “idlers” (sailmaker, carpenter and cook) and a crew of 20. The captain also had his wife and children on board.

As they approached Cape Horn the weather was a nightmare with tumultuous seas and head winds. Three seamen were lost overboard, three were battered so badly that one died after hanging onto life for weeks. One man was crushed when he was swept into the heavy steel waste-ports that let water drain from the deck on the lee side. His wounds turned gangrenous, and Captain Barker had to amputate a leg as the ship pitched and rolled off the Horn. They spent more than six weeks in the vicinity of Staten Island pummeled by heavy seas and bad weather before finally making enough westing to round the Cape and shape a course in a northerly direction.

After discharging their cargo of coal at Pisagua the ship moved north to Callao in Peru for repairs and new cargo. A survey revealed plenty of damage. The surveyors recommended that the foremast be repaired ashore, but Captain Barker knew the owners had no insurance and he resolved to save them money by removing the foremast at anchor and repairing it on board. Many of the crew had been too injured to go any further or had jumped ship — only the captain, the first and second mates, the apprentices, the idlers and six seamen were left, sixteen men in all. But they did have a steam-driven donkey engine, for which the captain had saved some of the cargo of coal.

Captain Barker planned the repair very carefully. It was necessary to lift the foremast vertically until the heel was clear of the deck and then rotate the mast and lay it horizontally on the deck. The foremast was a steel tube 130 feet long, two feet in diameter at the base and weighing about 10 tons. Over a period of many days the crew rigged sheer legs as a tripod using the fore and main yards, each 105 feet long, and the fore-lower topsail yard. Handling these heavy spars in the Pacific swell that rolled into the bay was very difficult, not made any easier by the fact that the operations were carried out under the eyes of all other ships anchored nearby.

Eventually the tripod legs were blocked into position and firmly secured. A four-part tackle was fastened to the peak of the tripod and the bitter end led to the steam-driven winch. The lower block of the purchase was secured by a wire sling so that 85 feet of the foremast lay below the block and 45 feet above, this gave a good balance so that lighter tackles could keep the mast vertical as it was eased out of the hull. The wedges were knocked out of the deck collar, the heel released from the keelson and order given to “Heave away – gently!” When the mast heel was clear of the deck, tackles were taken to the capstan and the heel pulled forward as the purchase carrying the weight of the mast was carefully slacked. This required very close coordination so that excessive strain was not placed on the tripod. Finally, the huge mast lay on baulks of timber which had been laid on deck to receive it.

A fissure was repaired by blacksmiths and then the whole procedure repeated to put the mast back. British Isles spent four months at Callao making the repair and waiting for a new cargo. In his book about his career (Log of a Limejuicer: The Experiences under sail of James P. Barker, Master Mariner, as told to Roland Barker) Captain Barker gives very few details about the repair; he treated the operation as almost routine, he was far more concerned with the first mate, who had encouraged some seamen to approach him at the height of the Cape Horn gales and suggest he turn tail to Port Stanley, in the Falkland Islands. He regarded this as mutiny and grumbled about the mate throughout much of the latter part of his book. One of the ship’s apprentices, W.H.S Jones, also wrote a memoir of his career (The Cape Horn Breed) that was published in 1956. Unlike Barker, Jones was intensely fascinated by the work needed to get the ship seaworthy and it is from his book that I got most of the description of the heroic repair.

Ocean Navigator contributing editor Eric Forsyth is a master ocean voyager, multiple circumnavigator and winner of the Cruising Club of America’s Blue Water Medal in 2000. His website is yachtfiona.com.