In 2010 the U.S. government decided to pull the plug on the Loran radionavigation system for budgetary reasons. As a result, here in the U.S., Loran has joined the fate of radar viewing hoods and radio direction finders.

A group of European countries (Denmark, France, Germany, Norway and the U.K.) that operate the northern European Loran chain decided to press on with loran, however, and are installing an improvement to the system called eLoran. The eLoran technique makes use of improved transmitter and receiver technologies, resulting in improved accuracy.

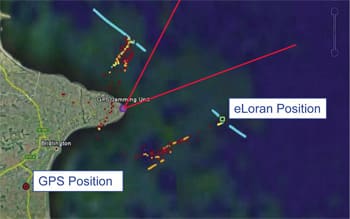

The main driver for this Loran improvement is not improved accuracy, however, but the threat that terrorists or criminals could jam or spoof GPS signals. Ships that rely solely on GPS would then have no electronic means for navigation. Voyaging boats are not as schedule-constrained as merchant ships, of course, and so have less worries about GPS jamming. On the other hand, losing GPS in a storm or period of low visibility could be dangerous to those voyagers who have become dependent on GPS and have let their other navigation skills lapse.

Now a further Loran modification is moving toward implementation in Europe. This version of Loran is called enhanced differential Loran or eDLoran and is being developed by the Dutch radionavigation company Reelektronica. The Dutch port of Rotterdam announced in March that it will develop an eDLoran system for harbor approach and navigation. The maritime authorities of these European countries want to ensure they have a backup system in place. Rotterdam, for example, sees 32,000 ship visits a year, plenty of potential for accidents and oil spills should GPS not be available due to jamming.

The differential approach involves broadcasting corrections to Loran receivers using the Loran signal itself. These corrections take into account the difference between a position derived from Loran and the known, surveyed position of a monitoring device. According to tests performed by Reelektronica, eDLoran can provide Loran accuracy down to five meters. The Loran system has the added advantages of operating on a different frequency band from GPS (LF vs. UHF) and of transmitting powerful signals not easily jammed.

The idea of differential Loran is not new. The U.S. Coast Guard tested differential Loran concepts back in the 1990s (I attended an impressive Coast Guard demonstration of differential Loran in Norfolk Harbor). Full-scale differential Loran capability was never added to the U.S. Loran system, however, prior to system shutdown in 2010.

In 2007, the General Lighthouse Authorities (GLA) — the U.K./Republic of Ireland organization for aids to navigation in the British Isles — began a 15-year program to implement eLoran in the U.K. Loran stations. That program, along with the Rotterdam effort, shows that Loran still has an appeal to government agencies tasked with providing radionavigation services to mariners.

In a move that could derail plans for adopting eLoran throughout the Northwest Europe Loran system, the French government is considering shutting down its Loran transmitters rather than invest to upgrade them to eLoran as the British/Irish GLA has committed to do. Martin Bransby, manager of research and radionavigation at the GLA has publicly stated: “A decision to close down the Loran stations would remove the only practical option for a backup to GPS in the near future… The need for collaboration is paramount in securing the future safety of our ships.”

The differential correction technique is also used for GPS. Monitor stations compare position information derived from GPS with their known, surveyed location. The difference is a correction that can be applied to a GPS position to make it more accurate. The original DGPS was a Coast Guard effort that broadcast corrections via radio beacons. That service, dubbed Nationwide Differential GPS (NDGPS) still operates and some receivers are equipped to use it. Later, an FAA system was developed called Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS). This approach uses monitors across the U.S. that determine necessary GPS corrections. These corrections are then uploaded to geosynchronous satellites and broadcast using a signal structure that allows WAAS-equipped GPS units to receive and apply them. A similar system, called EGNOS, is used in Europe and MSAS is used in Japan. Although some recreational-level GPS units use NDGPS corrections, most models now use WAAS corrections.

European concerns about reliance on GPS also prompted the European Union to move forward with its own satellite-based navigation system called Galileo. The 27-satellite constellation is expected to be operational in 2019 and will be inter-operable with GPS, allowing users with the right hardware to get position information from both systems. Galileo will also have a built-in search and rescue function allowing users to signal for help and to receive a return signal indicating that their distress signal has been received.

Although a capable European alternative to GPS in a time of crisis, Galileo will have the same Achilles’ heel as GPS: inexpensive jamming transmitters denying the relatively weak signal to users. Thus, the continued need for a terrestrially-based radionavigation system like eDLoran.