To the editor: With the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, it became abundantly clear that a huge military advantage would belong to the side that knew how to faster navigate the Atlantic. In order to obtain this advantage, one had to be knowledgeable regarding the highly potent collection of currents known as the Gulf Stream.

Though captains of all nationalities are now well versed in such information, back in the colonial era, the Gulf Stream — then unnamed — was quite a conundrum. It wasn’t a totally unknown force, however.

As early as 1513, conquistador Juan Ponce de León knew of the phenomenon. His voyage log describes a “current more powerful than the wind.” Additionally, the 16th century British explorer Sir Humphrey Gilbert was aware of such mighty currents. But it was the whalers from Nantucket who were the first to learn how to use the Gulf Stream to their advantage.

As Seymour Morris Jr.’s American History Revised relates, the whalers became curious about the course and speed of the Gulf Stream currents as they followed the migration of whales.

As with so many other early American developments, this one involves Benjamin Franklin. While in Britain in 1768, Franklin — then the deputy postmaster of the American colonies — was asked by a customs officer why it took British postal ships weeks longer to cross the ocean than their colonial counterparts.

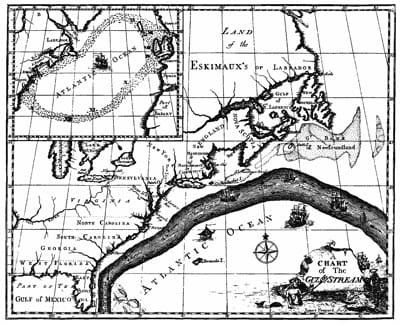

Franklin’s curiosity was aroused, a predicament which often lent to world-changing discovery. He sought out his cousin, Timothy Folger, who was a Nantucket whaling captain. Folger told Franklin about a certain stream of currents that had been discerned by observing whales. Having at many points measured the water’s temperature and the speed of the bubbles, the Nantucket whalers had been able to chart the currents.

Franklin proceeded to devote his talents to enhancing this intriguing nautical data. He offered it to the British Post Office, but they were uninterested. Franklin even published a Gulf Stream chart in Britain in 1770.

The British decision to ignore this material was one they would come to regret, however. Eleven years later, during the height of the American Revolutionary War, British ships were dispatched to Yorktown, Va., to help Gen. Charles Cornwallis in the coming battle against the Americans.

America’s French allies had strictly adhered to Franklin’s Gulf Stream chart. And so they had an advantage entering the Battle of the Chesapeake (also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes): a pivotal showdown between French Adm. de Grasse and British Adm. Graves.

The actual fighting was rather brief and not especially decisive. However, it was a strategic triumph for de Grasse, who blocked the British fleet from reinforcing the British ground forces led by Cornwallis. On the other hand, the American army received support from its French allies. As a result, the Americans outnumbered the British by 9,000 men.

As one could expect, Cornwallis was eagerly awaiting his reinforcements. On Oct. 24, the much-anticipated British ships arrived. By then, Cornwallis likely wasn’t too thrilled regarding their arrival, for he had already surrendered his army on Oct. 19. Hearing the news in London, King George III began to lament his “empire ruined.”

American History Revised holds that, had the British adhered to Franklin’s chart, their ships would have arrived at least two weeks earlier. This scenario may have changed the outcome at Yorktown.

The whalers of Nantucket provide for a fine example of observing the natural world. In this case, such knowledge likely saved America. The British eventually accepted the Gulf Stream currents. By then, however, they had lost their American colonies.

—Ray Cavanaugh is a freelance writer. His work has appeared in such publications as The Irish World, The London Magazine and The Tulane Review.