Peter McCrea raced to Bermuda on the solo leg of the 2015 Bermuda 1-2 Race aboard Panacea, a Freedom 32 cat sloop. McCrea and his son John were about to participate in the double-handed leg of the race back to Newport when they received debilitating injuries in a moped accident while sightseeing, knocking them out of the race. As a result, Panacea was left on a storm mooring in Bermuda and Peter and John flew back home to heal broken bones.

While recuperating, Peter sought a crewmember who could help deliver Panacea back to the U.S. east coast before hurricane season. Doug Theobalds, president of Epifanes N.A. Inc., was first to offer his time and extensive offshore experience, and Peter quickly accepted the offer. A few years back, the two of us had delivered Doug’s boat from Mystic, Conn., to Thomaston, Maine, and had served on committees together for a decade, so the critical “crew chemistry” imperative on a small boat at sea had been proven.

The boat retrieval mission started off with a hiccup when we arrived at the local regional airport only to learn the early morning flight was canceled since the assigned pilot was a no-show. As luck would have it, one of the passengers, coincidentally a senior vice president of Cape Air, saved the day. Without missing a beat, he personally rented a vehicle to deliver several passengers to the Portland Jetport and ferried us on to Boston’s Logan Airport to make missed connections. After an overnight stay in Boston, paid for by Cape Air (great service!), and an 0300 wakeup call, we headed to Bermuda via an 0530 flight to NYC with connections to Bermuda — a long day. Longtime friend Verna Oatley with her husband Bobby, owners of Captain Smokes Marina and the Godet & Young Hardware Store in St. George’s, had looked after the boat. They also assisted with transportation (avoiding renewed moped challenges) during our brief stay at their marina while provisioning Panacea for the 635-mile passage to Newport.

|

|

The Panacea crew reefed early and often, anticipating worsening conditions. |

|

Doug Theobalds |

Arrival

By the morning of Thursday, Aug. 6 — a scant two-and-a-half days after arriving in Bermuda — we felt ready to depart, having provisioned, scrubbed the hull, checked out all vessel systems, conversed with Gulf Stream and weather routing advisors, paid bills, etc. In the haste of leaving the marina, topping off diesel, making last-minute provisions (beer and olive oil) and clearing out with Bermuda Customs at Ordinance Island, we missed the 0730 SSB weather chat with Florida-based meteorologist Chris Parker and thus a vital element in a safe passage home. Plenty of time to catch it tomorrow, we thought, confident in knowing the forecast was for benign weather for several days ahead. Had we listened, Parker would likely have tried to discourage a departure at that time.

Underway

We departed with great relief at heading homeward with full water tanks and extra diesel. This setup was nothing like the light-ship configuration Panacea usually has when racing. The SSB long-range radio was used to contact a cruiser in Onset, Mass., who we asked to send an email to Chris Parker stating we were underway and would contact him at our next scheduled radio time the next morning.

At sunset, the seas and wind moderated from showery rainsqualls in Bermuda to quieter conditions, and by midnight we were motorsailing with the engine providing gentle thrust, moving the boat along at a little more than 5 knots. At that rpm, the diesel consumes less than 0.4 gallons per hour, giving us 500 miles of motoring range. A watch schedule was agreed upon to be two on/two off during the dark portion of the day and unstructured rest periods during the daylight with someone always awake and alert for alarms (bilge, AIS, radio sked, log entry, etc.) and visual watchkeeping.

Stream sucks

Our colorful paraphrase of what Chris Parker had to say on Friday morning was “stream sucks.” A massive energetic system akin to a nor’easter would create untenable sea states in the region of the Gulf Stream that Panacea was headed toward, some 300 miles to the northwest. No immediate alternative to turning back to Bermuda was offered, and we signed off to rethink our options. A decision to slow our 7-plus-knot rate of progress was made. The main was doused after securing first and second reefs as a precaution as we reached northwest on the small jib at 4.4 knots. Parker was advised of our new “go slow” strategy with a brief inReach message. Respond, he did — with a three-page imperative!

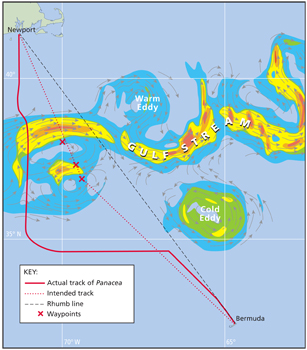

Go west

The essence of Parker’s advice was to head west. He warned us not to go north of 36° N until we reached a Gulf Stream entry point at 36° N and 72° W — a long way off the rhumb line course one normally takes, but this was not normal weather. He also cautioned that building southwesterly winds with squalls would be upon us Saturday on our way west. This option was preferred since it offered a path of avoidance of very nasty Gulf Stream weather at the expense of extra miles traveled while still heading for home … eventually.

Soon after 1630 on Friday, the double-reefed main was raised, the Monitor wind vane set to maintain a course heading west along 34° 40’ N, doing 6 knots through the water.

|

|

McCrea and Theobalds’ intended track was declared unwise due to predicted Gulf Stream conditions and they detoured to the west. |

|

Pat Rossi/Ocean Navigator illustration |

Wind is up!

By 1830 on Saturday the winds were 28 to 33 knots apparent, increasing to high 30s in squalls. The double-reefed main was handed with Doug doing all the deck work and Peter advising the sequence while working the cockpit. Continuing under small jib alone with the Monitor steering, Panacea was doing 5.4 knots over ground, heading slightly north of west.

By midnight Saturday, Parker’s Gulf Stream entry waypoint target was 132 miles distant, bearing 323 degrees magnetic. Wave action was increasing but did not appear to be threatening. Panacea was comfortable and not overpowered despite the deteriorating conditions.

Knockdown!

At 0300, squally conditions saw Peter on watch, sitting on the perch in the companionway just inside the “offshore slider,” which closes off the belowdecks space from the cockpit with a 5-by-24-inch opening at the top. Doug was off watch in his bunk in the aft cabin. As quick as a blink and with no breaking sea pre-warning roar, Peter became horizontal with water pouring in through the small slider opening, accompanied by a cacophony of sound as loose objects followed parabolic arcs across the cabin to land on the nav station and leeward berth. Doug awoke laying on a hull-mounted port light and emerged quickly from aft as Panacea righted herself and resumed sailing with an added load of seawater and flailing jib, its top third severely compromised.

|

|

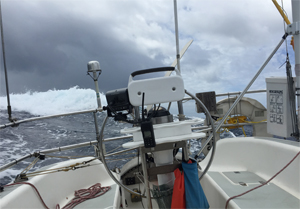

Panacea’s Monitor wind vane, steering here through breaking seas, was key to Panacea’s safe arrival. |

|

Doug Theobalds |

Chaos and smoke

The bilge alarm sounded as the six inches or so of seawater in front of the nav station began to filter below while we tried to capture and bail as much as possible with a dishpan. A dozen eggs in their container mysteriously appeared on top of the nav station, along with much of the contents of the spice rack on the opposite side. None of the eggs appeared to have suffered from the 12-foot arc across the galley from inside the ice chest to the nav station lid.

A serious new threat quickly emerged when acrid smoke appeared at an access slider adjacent to the 12V electrical panel. A search for the ignition source proved useless as the fumes quickly became thick, black and acrid. It became absolutely impossible to breathe down below, forcing us both out into the cockpit. Without a lot of discussion but a shared belief that something had to be done, Peter, with fire extinguisher in hand, dove back into the cabin and shut off the three battery switches in three different areas of the boat, thereby nipping the source of the electrical fire at its origin. A second trip below left an open galley hatch to windward, resulting in rapid clearing of the cabin atmosphere in order to regain the shelter of the cabin to assess the damage.

Doug deployed the cockpit-mounted manual pump and drew air after 150 strokes. With all electrical power off, we were basically “dead ship,” but with the Monitor steering and the damaged jib still pulling — albeit noisily — we were still making westing to slightly north. It was agreed that little more could be done after the cabin sole had been cleared of detritus and trip hazards, and we both retreated to individual berths to think through the situation.

|

|

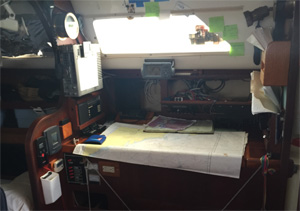

The nav station was ground zero for a lot of seawater and a few egg cartons. |

|

Doug Theobalds |

Assess

During the next few hours we got little sleep as we talked through the possibilities of getting lost functions back online. Daylight brought a slight moderation in conditions and a sense of optimism when we discovered the engine start battery and circuits as well as the independent SSB/tricolor/GPS battery and circuits (a Bermuda 1-2 requirement) were unaffected by the electrical fire — just the main house bank and its 20 breakers were inoperative, including chartplotter, all three electric autopilots, nav lights, cabin lights, propane solenoid, bilge pump, wind instruments, radar, VHF and AIS. We did a visual inspection of the engine compartment, paying close attention to the engine mounts. Then we started the engine and ran it in gear to ensure that no lines fouled the prop and that the shaft was not bent. We also energized the SSB circuit and found its functionality was intact but the radio itself appeared unusable. Fortunately, the inReach communicator was functional for text communications.

Regroup: 12V jury-rig power

Doug handed the dying jib while Peter engaged the engine in improving sea state with the waves now on the quarter. An electric autopilot was necessary to hold a satisfactory course, so a jumper 12V feed from a live “good” circuit was run to the nearest autopilot with inelegant but adequate results considering our situation. We used a similar patch and soon the stove was working so that an accustomed morning jolt of dark roast was assured. When we lifted the nav station lid we found containers of olive oil and wasabi from the spice rack and a second egg carton with 10 eggs, along with seawater-saturated charts. Only two eggs were cracked. We conjectured that this was the first carton of eggs to land as the nav station lid was perhaps forced open either by water pressure or by the rotational energy in the knockdown. Makes one wonder about the Newtonian mechanics of full egg cartons at sea. Another strange flight path was the one taken by a copy of Vertue XXXV, a slim volume describing a noteworthy trans-Atlantic passage in a 25-foot sloop authored by the founder of the Ocean Cruising Club, Humphrey Barton. The book was found wedged into a centerline overhead handhold, as if the author wanted it to be the last item to remain dry.

|

|

The damaged SSB antenna hints at Panacea’s deep roll angles. |

|

Doug Theobalds |

Stream crossing

Chris Parker predicted good stream-crossing weather “just around the corner to the north,” and sail was soon added to the engine assist to drive to the waypoint. By Monday at 0800 Panacea was reaching at 6-plus knots with no engine, heading across the Gulf Stream in bright sunshine. Parker warned, however, of increasing winds and strong convection with squalls to 60 knots occurring on Tuesday on the track to Newport. And then there was a further surprise: We encountered some of the largest mature waves Peter had seen in his 24 crossings of the Gulf Stream — monsters that we were sure spanned 25 feet from crest to trough. The scene was both awe-inspiring, and humbling. Early on Tuesday morning we set both the first and second reefs as a southerly wind increased. A third reef was added two hours later, the latter small sail area being quite compatible with the Monitor steering on a broad reach. The weather worsened, making the third reef the right choice for most of the day, but by dark it was clear we had dodged a bullet and were spared the worst part of the predicted system.

Smiles

Just south of the Nantucket shipping lanes the wind was down, so we fired up the engine with 58 miles to Brenton R2, the entry buoy to Newport. Panacea passed R2 close aboard at 1010 Wednesday morning, Aug. 13, after six days and 796 miles since leaving Bermuda.

Observations and lessons learned

A conclusion to any story is essential, and this one is no less deserving. There are always lessons learned. Firstly, we reviewed the time prior to the “incident.” We previously agreed that Panacea was not overpowered for the conditions. Had the wave intensity risen to a severe state we could, or likely would, have dogged the leeward head hatch — typically kept ajar for some cabin ventilation — fastened the latches on the ice chest and nav station lids, and installed the top closure panel on the offshore slider. These actions would likely have kept most of the water out of the interior of the vessel, preventing the electrical fire. Loss of the jib would not have been prevented.

|

|

Panacea waiting for customs clearance after arrival in Newport. |

|

Doug Theobalds |

By far the greatest asset during recovery was Peter’s intimate relationship with Panacea. His mental picture and thorough knowledge of the workings of the vessel proved critical time and time again. With this level of familiarity, and a well thought-out toolbox, we were able to right essential systems and continue in relative comfort and safety.

The sea state and wind conditions were challenging at best during the passage. There was temporary relief a couple of nights and, at last, a glorious morning the day we made landfall. Despite the considerable challenges, we remained calm and were able to share ideas, suggestions and opinions. Never did we raise our voices or speak harsh words. In spite of the chaos and incidents experienced, we agreed the trip was a success.

It is good to remember that most boats can withstand far more than their crew. Skippers must know their boats inside and out, and remain clearheaded, calm and in control as quickly as possible after the unexpected happens. Panacea was fortunate to have two good seamen aboard. Needless to say, Peter was extremely pleased with his choice of Doug to help fetch Panacea home.

Peter McCrea has logged more than 70,000 miles in Panacea, crossing the Atlantic twice. Doug Theobalds is a sailor and president of Epifanes N.A. Inc.