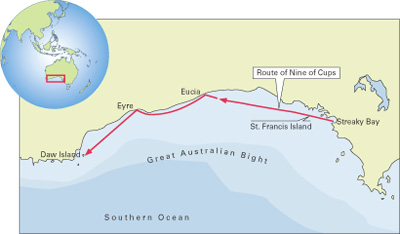

Whenever we’ve read articles or spoken to people about crossing the Great Australian Bight, the advice has universally been “wait for a weather window and get across as quickly as you can.” Then we happened to meet a fisherman who’d spent years in the Bight and his recommendation was quite different. “Don’t be afraid to get up into the Bight,” he said. “It’s a beautiful area and there are places that you can anchor to protect yourself from the winds.” We started to think about things a little differently. Though we were obviously keen to get across safely in our Liberty 45 cutter-rigged sloop Nine of Cups, we’ve never been known to hurry; so, we looked into the possibilities.

It’s not that we didn’t trust the word of many, but listening to the fisherman’s advice was compelling — it just made sense. We wouldn’t require such a long weather window to cross, the passage could be broken up into shorter overnight legs and we’d actually see something of the Bight’s beauty. We perused the Western Australia Cruising Guide, but it offered little detail on anchorages in the northern part of the Bight.

|

|

With the benefit of local knowledge imparted by Bight-based fishermen, the Lynns successfully anchored at several rarely-visited locations in the Great Australian Bight. |

|

Alfred Wood/Navigator Publishing |

We talked to more folks about trying a different approach to the Bight crossing. Some had crossed the Bight before, some had not. They all agreed, however. “It’s the Southern Ocean,” they said. “Just get across.” Some told us to go as far north and west as Ceduna as a jumping-off point. Others thought just sailing directly from Port Lincoln made more sense, just to get it over with. We opted to leave from Streaky Bay. Whether you’re jumping off to cross the Bight or arriving from the west, there’s not a more beautiful place.

Gust damages yankee foresail

We started out slow and easy with a 50-nautical mile passage to St. Francis Island on advice from some local sailors. The passage was great until the clew ripped out of our two-year-old yankee foresail in a paltry 20-knot gust. We barely got the yankee furled as much as we could when we were “attacked” by a series of vicious roll clouds (a.k.a. morning glories) that spawned 35+ knot gusts. With only a postage stamp of a loose foresail flapping in the wind, we couldn’t get our new anchor to set properly in the weedy bottom of the St. Francis anchorage. Typical of calamities at sea, they all seem to come at once when you’re the most tired and aggravated. In the lea of the island, we finally managed to get the foresail down and clumsily stuffed into a sailbag, the anchor finally caught and the roll clouds headed east to attack some other unsuspecting sailors.

We waited out two days of strong southwesterlies, then with east winds forecast, a spare genoa on the forward furler and better dispositions, we headed not straight southwest across the Bight, but rather west to Eucla. Looking at Eucla on our chartplotter, we saw nothing but open bay. Our fisherman friend, however, had provided us with a hand-drawn chart of the entrance to the anchorage behind shallows and sand bars. We entered at longitude 129º E where the color of the cliffs changed markedly from white to black. We proceeded straight until we were about a half-mile from the shore, then turned due west and headed toward the old jetty, noted on the chart. The pale aquamarine water was considerably calmer than outside the anchorage and the sand bottom was a welcome sight. We dropped the hook and it dug in immediately. We heaved a sigh of relief. Before we could even tidy up the lines, swallows lined the whisker pole and rails and chirped us their welcomes.

|

|

The clew tore free from the Lynn’s two-year-old yankee foresail in only 20 knots of wind. |

The wind howled for the rest of the day from the SSE, reaching 25 to 30 knots with gusts near 35 knots. We pitched a bit, but the motion was certainly tolerable. The shallows and sand bars absorbed much of the wave action. We held firmly. I might add that we are a heavy-displacement boat (20 tons) and a smaller, lighter boat would most certainly have found the conditions less tenable.

The winds calmed during the night and with a beautiful day dawning, we launched the dinghy for a trip ashore. The walk along the fine, deep sand beach was challenging. The historic old jetty was totally dilapidated, its few remaining intact pilings lined with cormorants and gulls. We found a rough four-wheel drive track leading across the bush and up towards the Eyre Highway. The flies were merciless which made photography a labor. David swatted while I snapped. An emu emerged from the bush and strolled across the road, apparently unconcerned with our presence.

Old telegraph station

We came across the crumbling remains of an old telegraph station, nearly engulfed in sand. It seems in the 1890s, a rabbit plague passed through the area and ate much of the dune vegetation, subsequently allowing sand dunes to encroach upon the town. The original town was abandoned, and a new townsite was established a few kilometers to the north, higher up on the escarpment. The telegraph station, a few leaning telegraph poles and one old foundation are all that’s left.

|

|

The sand-drifted ruins of the 19th-century Eucla telegraph office. |

About three miles in, parched and hungry, we climbed the hill to the Eucla Roadhouse, a welcome stop for those crossing the Nullarbor, as well as errant sailors. After a quick sandwich and a cold drink, we met a woman who worked in the restaurant. She asked if we were passing through and we told her we had sailed in and were anchored by the jetty. She perked right up. “We saw the sailboat anchored there and wondered who it was. We’re lucky if we see one yacht anchored here a year.” She then proceeded to offer us a ride back to the boat. We gladly accepted her generous offer. We chatted as we drove and talked about heading perhaps to Twilight Cove, an anchorage we knew little about further up the coast. She stopped the car, turned around and headed back up the road to her home. Her partner, Paul, was a fisherman who had fished the Bight for the past 27 years. He could provide us some firsthand information about other anchorages in this part of the Bight. Talk about luck! Paul immediately produced a well-worn chart and his fishing notebook and proceeded to give us detailed information about Twilight Cove, Eyre and other anchorages including depths, lats/longs and hazards. It was like manna from heaven.

|

|

A flight of swallows greets the Lynns on their arrival at Eucla. |

Off the beaten path again

Our conversation with Paul gave us the incentive and the information we needed to stray off the beaten path once again. David looked at the proposed passage from Eucla to Daw Island, 300 nm, and wondered if there wasn’t some way of breaking up the trip. Eyre was only 170nm — two days and an overnight. To add icing to the cake, the Eyre Bird Observatory there is the most isolated research facility in Australia and is home to 240 species of birds. Researching the observatory online, David found an e-mail address for the volunteer caretakers, sent them an e-mail inquiring about the anchorage and lo and behold, we had an answer within hours. They actually got in touch with a local cray fisherman and were able to corroborate Paul’s information about anchorage depths and entrance coordinates, enabling us to maneuver around the sand bar and shallows that provide protection to the bay. The weather seemed to be cooperating and we were off.

The passage from Eucla was a quick broad reach and the coordinates that our Eucla friend, Paul, and Vince the cray fisherman in Eyre provided were spot-on. The landmark to look for on entry is the Eyre Sand Patch, a huge sand dune, noted and named by Edward John Eyre on his historical first trek across the Nullarbor Plain. It’s hard to miss.

|

|

Nine of Cups anchored off the beach at Eyre. |

Eyre is not a port, but rather an anchorage that a couple of cray fisher boats call home in season. Other than the Eyre Bird Observatory, the closest neighbor is the Cocklebiddy Roadhouse about 30 miles away and access to the Observatory off the Eyre Highway is 20 miles on a four-wheel drive road that purportedly shakes your dental fillings loose. Or you can arrive by sea, anchor in the backyard, dinghy ashore, walk a half a mile and call in for tea.

Despite the gray and overcast sky, we headed to shore the next morning. The sandy beach trail led through dunes, up a narrow, four-wheel drive road and into a small, very green valley with lots of flora and birdsong. Signs and lengths of hawser marked the way. We could see the tin roof of the Observatory nestled in a little hollow as we crested the hill.

In 1977, Birds Australia established the Eyre Bird Observatory in the remains of the first Eyre Telegraph Station, a repeater station built in 1877, and replaced by the current limestone building in 1897. We shared a cuppa with our hosts, Kirsty and Gavin, on the veranda. They provided us with an introduction to the observatory and then turned us loose to have a look around and explore several of the footpaths and tracks in the area.

As we walked, we felt protected by the huge dunes on the seaward side, but when the breezes became a bit brisk, we began worrying about the boat and returned to the station to say our farewells. We would have enjoyed several more of the illustrated walks in the area but a brief visit was definitely better than no visit at all, and so we headed back along the sandy trail to a waiting Cups.

|

|

A sign points the way to the Eyre Bird Observatory. |

Adventure in the dinghy

Getting back to the boat was no trivial affair. The wind was up and with it, the surge. We dragged the dinghy into the water, keeping it straight into the waves as they broke. When we were near thigh-deep, we timed the waves and when there appeared a short respite, I jumped into the bow and began paddling like mad. David shoved, then jumped in over the stern, losing his shoes and taking up a paddle in one swift motion. We thought we were good and David stopped paddling to start the engine. A wave larger than the rest caught us, pooped the dinghy, and turned us broadside to the next wave, which carried us with some alacrity back to the shore. So, the process repeated and repeated. Finally, on our umpteenth try, we made it beyond the breakers and were on our way back to Cups. We were dripping wet and totally bedraggled.

Tying up the dinghy with the waves thrashing took the both of us. Clambering aboard Cups from the jerking dinghy was not a graceful affair, and still we had to haul the engine and get the dinghy aboard. David always takes the precaution of fastening a line to the engine and securing it to the boat, so we don’t lose it overboard. It’s never happened, but you never know. Especially in boisterous situations, I hold the line taut as he’s loosening the engine bolts that secure it to the dinghy. Quicker than you can say, “Yikes, the engine’s heading for the drink,” I was wrestling to keep hold of a 50-pound engine blowing in the breeze after it came loose from the dink. It dangled ever so closely to submersion level. David was up in a flash, hauled the engine and had it secure in its mount.

|

|

A sea lion folows the dinghy at Daw Island. |

Now, it was time to haul the dinghy. We use the windlass and a pulley system which gets it on board in a matter of minutes. I’m pleased to report the dinghy was stowed in its place on the foredeck with no mishaps and only a few bruises.

Daw Island was next on the itinerary. The first question was, “Where is Daw Island?” It was difficult to pin down its exact location. Our Australian paper charts gave the anchorage position at one location. Our Raymarine chartplotter showed the position of the anchorage about 3.75 nm further east. We use Navionics Gold software on the chartplotter, but also have Navionics on our iPad — even the Navionics software on the two devices differed. The satellite view provided by Google Earth gave the position of the anchorage about 0.25 nm west of the chartplotter location. We headed for the general location.

The run from Eyre to Daw Island was quick and bumpy, 148nm in a little more than 22 hours. The southwest swell coupled with a brisk east wind and corresponding waves contributed the majority of the bumps. Considering we weren’t really sure exactly where Daw Island was, we were keen to approach it in daylight. There were several other low-lying islands and islets in the vicinity, and since Daw was apparently mislocated on the charts, perhaps these were, too?

Ogre’s lair in the dawn light

It was a gray dawn made duller by gray skies and a gray sea, with a kicker of a gray swell the day we made landfall. An early morning mist, then rain, kept the suspense heightened since we never saw Daw until we were less than 10 nm away. Sticking out of the ocean nearly 300 feet, we finally spotted it: a multi-hued gray silhouette rising out of the sea, looming ominously, a darker gray cloud hovered over it. It looked like the home of some fairy tale witch or ogre. But a sea eagle soared overhead just then and dolphins joined us — how bad could it be?

Just as we’d hoped, the island curved around, enveloping a lovely, millpond-calm anchorage. Bird sounds accentuated by the barks and yips of sea lions along the rocky shore greeted us. Despite the gray skies, sand patches were evident in the clear water and we dropped the pick in 25 feet off a sandy beach and it hooked immediately.

|

|

A sea lion welcoming committee in the shallows at Daw, the western end of the Lynn’s passage across the bight. |

The following morning was glorious. In a word, Daw Island is magic. We landed on the white sand beach as sea lions languished in the morning sun. They watched us warily and quickly headed for the water. More confident in the water, they followed our movements up and down the beach with curiosity. We had planned to hike to the high point for views, but were soon deterred by a faded, but clear warning sign: Death adders reside in large numbers on this island — so much for views.We contented ourselves with beachcombing and walking the beach where gulls, terns, oystercatchers and Cape Barren geese seemed to be enjoying the morning sun as much as we were.

We considered Daw Island in the Eastern Recherche Group to be our last bit of the Bight. It had taken us 10 days and we sailed 628 nm. We had encountered no significant weather in our crossing. By going further up into the Bight, we had avoided the major impact of huge waves as they traveled over the deep terraces, canyons and troughs to the shallower Bight waters. We took our time and had the chance to visit places we would never have visited otherwise. All in all, it was quite an enjoyable passage. In retrospect, if we cross again, we’ll do it the same way.

Marcy Connelly Lynn lives aboard her Liberty 45, Nine of Cups, with husband David Lynn. Now in Fremantle, they continue the slow circumnavigation they started in 2000.