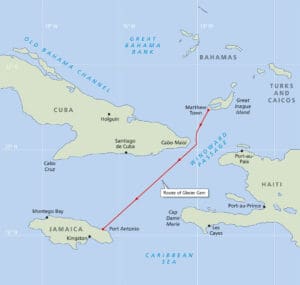

The 238-nautical mile voyage from Matthew Town, Bahamas, to Port Antonio, Jamaica, was a navigationally interesting one. Our route transited the Windward Passage between Cuba and Haiti close to the Cuba side where a traffic separation scheme is in place. Though relatively short, the dogleg path made things slightly more challenging than our previous open water crossings with no obstructions. It also provided some coastal navigating opportunities. Additionally, our path passed about eight nautical miles from dangerous reefs near Jamaica. One of those reefs is only 16 feet deep with large breaking swell and an exposed shipwreck.

My wife Monika and I are circumnavigating aboard our 50-foot, Thomas Colvin-designed junk-rigged aluminum schooner Glacier Gem and are navigating primarily via celestial navigation. We are frequently asked what happens when it’s cloudy and we are unable to take celestial sights. The plain truth is that we sometimes don’t know exactly where we are and our position can be worrisome. That is just how it is with intermittent fixes, probably the biggest drawback to celestial navigation.

We have a chartplotter onboard as a backup to our celestial navigation. The chartplotter is a great resource and is available to be switched on at any time. We did not use GPS during this voyage with the exception of recording three GPS positions for later comparison when the trip was complete. The GPS positions in no way influenced our decision making while underway. Having a few GPS positions makes it possible to analyze the navigation afterwards using independent comparison data.

Drawing a chart

Unfortunately, we did not have paper nautical charts for this part of the world, instead, we made our own on a large plotting sheet. We would have preferred properly corrected paper nautical charts from a reliable source for this leg, however, outside factors prevented it. Deepwater prevails throughout most of the route and we were comfortable with our plan.

To construct our chart we used lighthouse position coordinates from the NGA Light List to place the relative positions of the Bahamas, Cuba, Haiti, and Jamaica landmasses. The coastline shapes were freehand copied from PDF nautical charts which are available online.

Next, we recorded the route waypoints in our rainproof logbook and drew additional overall and harbor approach sketches. We highly recommend this step even if you don’t bother with celestial navigation. It is a resilient record in case of electrical failure. The final step was to draw our intended track on the plotting sheet chart. This makes it easy to check progress and can improve decision making.

The voyage

We departed May 10, shortly before nightfall on a 41-nautical mile leg to Windward Passage. This was intended to put us at the start of the passage on the following morning, but the weather did not cooperate.

We sailed approximately 12 nautical miles from Matthew Town and the wind died completely. This caused us to drift overnight within visible range of the tall lighthouse in Matthew Town while numerous thunderstorms brewed overhead. The lighthouse beacon allowed us to visually estimate our position through most of the night.

Unfortunately, the Matthew Town light was not visible just before daybreak, due to clouds and thunderstorms. We were unable to get a final exact distance and bearing to the light. We estimated our distance to be 12 to 15 nautical miles off the light at daybreak on day 2. The swirling winds and currents made it difficult to accurately judge our overnight position while we drifted aimlessly.

After daybreak, the wind picked up and we finally made way following our compass course towards Windward Passage. We deployed our vintage 1890s mechanical taffrail log to record our distance through the water. We also used a chip-log to periodically measure our speed. Like other sailors, my wife and I share vessel responsibilities. Navigation is my responsibility. I am responsible for its success and consequently its possible failure.

During mid-morning, I was able to get a sun-moon fix. The fix did not agree with our dead reckoning (DR) position. It put us 10 nautical miles away from it and was highly questionable to me. Sometimes ambiguity is just how it works with celestial navigation. Sometimes you just don’t know exactly where you are. Like a criminal detective, you always second-guess everything.

I was highly suspicious of the sun-moon fix but was unable to get any accurate results to counter the information. I needed a three-LOP star fix, but it was the wrong time of day. The DR positions put us in the right location, but the celestial sights showed our course to be dangerously aligned with an approach to the opposing traffic separation lane!

I switched to the backup sextant to rule out the primary sextant as a possible factor to the error. The primary sextant is one my grandfather used as a professional mariner. It is a reliable C-Plath made in Hamburg, Germany. I have never detected any problems with the sextant. Lately I’ve been getting some erratic sights, which I suspect is from an unidentified personal error. The results from our backup sextant confirmed we were approaching the opposing traffic separation lane. The fact was, four sextant sights using two different sextants were consistent with each other. It was almost undeniable that our DR position had some serious error. I assumed we must have had encountered unexpected ocean currents overnight while drifting around with thunderstorms.

While I was working to positively resolve the discrepancies, Monika raised Cuba on the horizon. Our taffrail log proved to be invaluable because Cuba was in such thick clouds that we couldn’t spot the mountainous coast until we were less than 12 nautical miles away and even then it was just a debatable thin shadow. We should have been able to see the coast at more than 25 nautical miles! In order to positively identify the coastline in the humid and misty weather, we changed course and passed within five nautical miles of land.

We chose to sail close to the eastern tip of Cuba, Point Maisi. I had planned to remain a minimum vertical sextant angle of 0° 11’ off the lighthouse. This sextant angle would ensure that we would stay in the southbound traffic lane, remain in deep water, and be more than an arbitrary 6 nautical miles off the Cuba coastline. The US Sailing Directions are very clear that mariners should stand well off Cuba territorial seas (12 nautical miles) to avoid boardings. Cuba has been known to board vessels 20 nautical miles off their coastline. I cut it a bit closer than initially intended.

We planned to see one last fixed aid to navigation on the other side of Windward Passage, a lighthouse, at Point Caleta, Cuba. Then a 178-nautical mile leg to Jamaica would be the only remaining task.

We were passed by several large container and tankships in the separation scheme. Our close proximity to the shoreline posed no obstacle to them. Sailing vessels shall not impede power vessels in these schemes. We observed only three small fishing boats off the coastline and were not boarded by any Cuban patrol boats. In fact, nobody seemed to even notice our presence.

The rest of the way

We were able to get a bearing on Point Caleta Light as we passed by. The bearing allowed us to regain an accurate DR position fix and departure. Twelve hours later, we got a solid sun-moon fix which put us four nautical miles to the right of our trackline. Since the wind was dead astern at 15 knots, we were tacking downwind. It’s easier to tack downwind at an angle than to go directly downwind with our junk-rigged schooner. We soon crossed over our trackline again.

In the afternoon, we decided another position fix was needed. We planned to get an evening three LOP star fix. Clear blue skies had dominated all day, but right when nautical twilight arrived, clouds suddenly formed and obscured the sights.

More heaving-to was required during the night as thunderstorms passed over us. The night sky was cloudy and the moon didn’t rise until early morning hours. As we do not have an autopilot, this made it a tedious task to follow a compass course while sailing. Usually, we point at a star on the horizon and follow it instead of tracking the swinging compass, but that wasn’t an option with the dark obscured sky. On top of that, the red colored compass LED light malfunctioned to a blinding white light only. Every time we consulted the compass we lost our night vision.

Once again, our position confirmation was desirable. I planned for another three LOP star fix at morning nautical twilight. I woke up Monika so she could take the helm and maintain our course. When morning nautical twilight came, I initially got a star sight on Sirius, but my watch was turned sideways on my wrist. I couldn’t read the time at the critical moment. I tried again and got the sight. That’s when I accidently dropped my pencil, which fell point down, and broke its lead on the aluminum deck. While I was picking up the lead, and repeating the time outloud so I wouldn’t forget it, the sextant caught on my lifejacket and changed the index arm setting. That was also the moment I realized I needed to use the head. I hadn’t been able to leave the helm because I had been on watch during the morning hours while Monika was sleeping. Now my body wasn’t going to wait for a more convenient time. After resolving those problems, I recorded a three-star sight. Of course then I realized I had been reading the timepiece incorrectly and the times were all wrong! At night, my analog watch second hand marker glow is opposite the pointer. All of the readings were 30 seconds off. As the way things had been going, when it rains it pours, one of the stars went behind a cloud and the other two stars disappeared in the daylight!

Throughout the morning, I tried to obtain a good solid sun line to advance later in the day. I intended to take a single line of position and advance it by the distance run to a sight taken hours later and get a running fix. Unfortunately, sometimes it just doesn’t work like that. It remained cloudy.

At 1815 hours, we sighted the Jamaica coastline approximately 24 nautical miles ahead. Once, years ago when learning to navigate, I made a nighttime landfall to a harbor. After approaching the harbor for quite some time, I realized that the navigation aid light sequences did not perfectly coincide with the navaids on my chart. It soon became apparent that I had made an approach to the wrong harbor. The harbor had a nearly identical light sequence as my destination. I was 15 miles short of my harbor and almost didn’t detect it. Sometimes the human brain will convince itself that everything looks as it should, until it’s too late, and you’re aground! That can happen with traditional and modern navigation. Reliance on a single source of information can be fatal. I am much more careful now, but there are no guarantees in life nor in navigation.

We watchfully approached the coastline, being mindful of the submerged reefs and wrecks of unlucky sailors. We had initially timed our arrival for an hour past daybreak, but our trip took longer than intended. Now we found ourselves with only one hour to spare before darkness. We needed to correctly identify Folly Point Light, off Port Antonio, Jamaica.

Folly Point light is described in the NGA Light List as a white colored tower with red colored bands. The tower we were looking at appeared to be the opposite. It was red colored with white bands. It was one of those subjective situations that doesn’t matter in good conditions but can mean life or death in poor conditions.

Many of the lights in the Caribbean are less than ideally maintained. It is not uncommon for lights to be extinguished or nonexistent. I still don’t know if the light was working as it was daylight when we safely passed it. Upon approach to the harbor, we were initially concerned that building waves, up to 12 feet, would affect our arrival. The waves slowly dissipated as we got closer to shore.

The coastline matched our expectations and there were no other nearby ports, so we continued our approach despite the minute discrepancy. The entrance to Port Antonio was straightforward and mostly as expected. A system of range lights is installed to pass between rock walls into the West Basin. The only real surprise we found was that the western most range is positioned high on the side of a mountain, its elevation makes it not immediately apparent. It was a quick and positive arrival.

I do have to admit, I turned on the depth sounder for the approach as I didn’t feel like swinging the leadline under the time constraint and it was very deep.

Debrief

After every trip, I do a self-debrief where I can analyze all data which includes examining the GPS positions recorded. This is one of the best ways to improve skill levels.

The short evening on day 1 only required following a compass course. No sights were taken, so there was nothing of note to review.

The GPS position recorded on the afternoon of day 2 was consistent with the celestial sights. Careful review found my error. I drew the starting location point on Matthew Town Lighthouse 10 nautical miles farther east than its true position. A significant mistake. The DR plot was started from this location which is why there was an unusual 10-mile discrepancy between the track and the celestial sights.

A sun-moon fix in the morning hours of day 3 found our position within four nautical miles of our trackline. This provided great results that were consistent with all of the data taken. Our recorded GPS coordinates showed the celestial fix to be within one nautical mile of our actual location at that time.

An evening star sight of Sirius resulted in a nearly 10° error (600 nautical miles). This is my unidentified personal error surfacing again. I double checked all inputs and reduced the sight multiple times. I prefer to directly reduce sights using a scientific calculator, but I even pulled out HO 229 tables for this one. This discrepancy was made somewhere on the reading of the sextant. Perhaps I caught the index arm on my lifejacket again. I still do not know how I created this error.

On day 4, as we approached the coast, two sun lines were taken despite mostly overcast skies. Poor geometry of the resulting position lines did not support a perpendicular crossing fix. However, the lines were able to show our distance off Jamaica and were very close to the trackline. Their accuracy gave us confidence for continuing an approach to the Jamaica coastline.

It can be very rewarding to make a successful landfall using traditional methods. While we love doing this, prudence dictates that using all tools at one’s disposal is the best way to go.

Traditional methods need to be practiced to maintain sharp proficiency. The skills are easily dulled or forgotten. We are thankful that the weather and location was suitable for us to explore our passion of celestial navigation on this voyage. n

Nick Massey and his wife Monika are circumnavigating primarily using celestial navigation. They hope to inspire others to follow their dreams. More info about their travels can be found at www.SailingGlacierGem.com.