In response to last year’s severe drought, the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) reduced the number of ships allowed to transit daily from a normal 36 to 22. According to Noonsite, the ACP also announced that only one of those would be an unbooked transit. Numbers are up slightly for January but as all vessels under 125 LOA go unbooked (i.e. can’t reserve a specific transit) this will cause extensive delays for transiting sailboats and power yachts during the high season. In addition, special lockages that allow rally groups to go through without a merchant vessel have stopped, and the boats will have to queue up as regular customers.

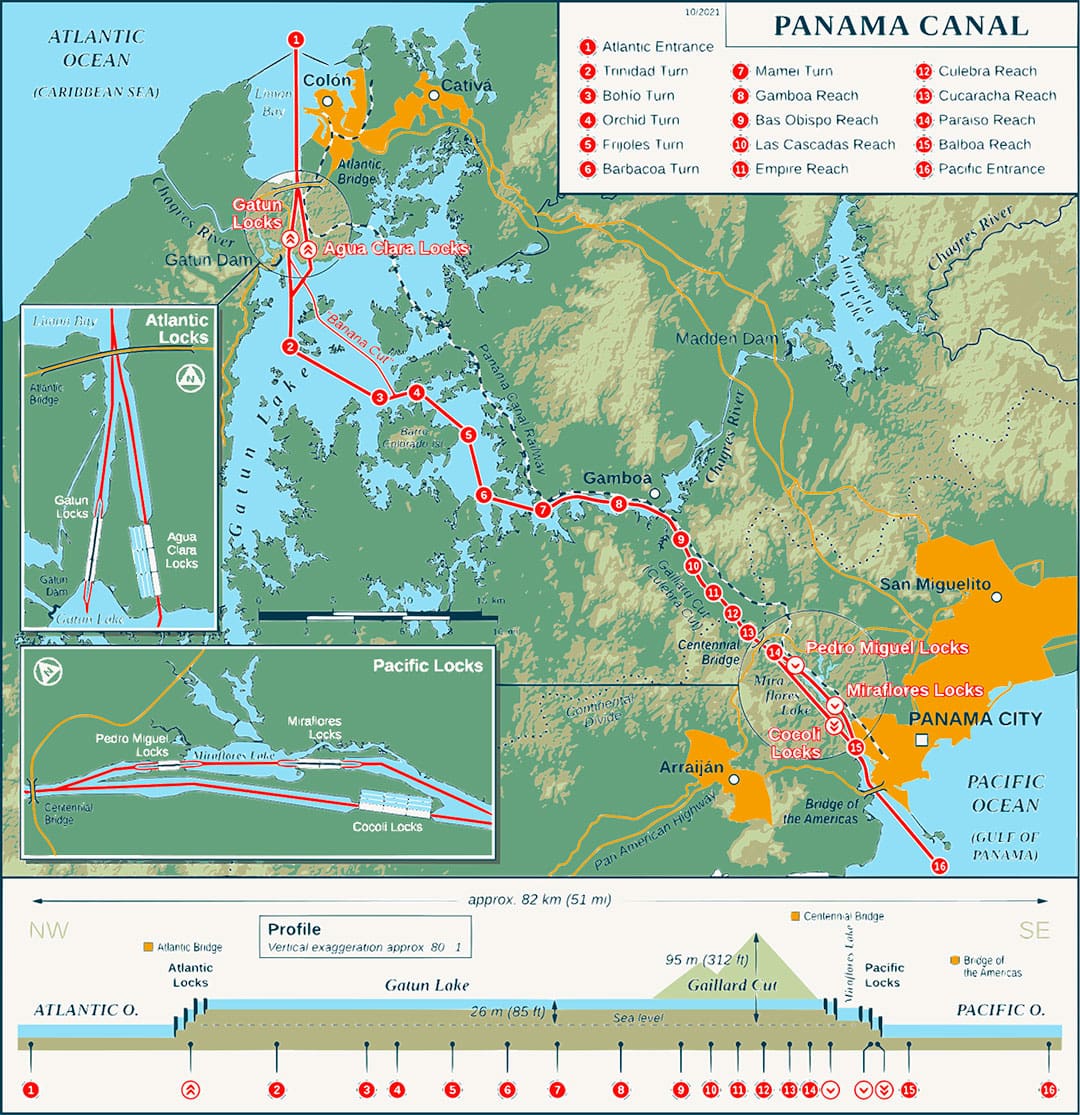

And the drought continues. The canal is not a sea level route and as it crosses between the Atlantic and Pacific it rises 85 feet to Gatun Lake, an artificial body that was created by damming the Chagres River. Besides feeding the canal the lake is used for electricity generation, irrigation, and domestic water supply.

Vessels negotiate a series of locks that use gravity to move them in steps. At sea level on either side, vessels enter a long holding pen. A set of gates is closed when they are tied up, shutting out the sea, and water flows in from the next pen up. When the water level in the pens is equal, gates in front of the ship open and it proceeds into that second pen. The ship rises until it can travel across the lake to be lowered through more locks, reversing the process back to sea level.

To raise one ship requires 50 million gallons of fresh water fed into the inbound locks, and that water is lost when the ship is lowered. The canal can’t deplete the lake below working level. The level at the end of the rainy season used to average 86.7 feet. This year it is expected to only reach 81.7 feet. Hence the need to reduce the number of transits.

The current drought was caused by the El Nino-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) which reduces rainfall on the Pacific side of Central America. The last year Gatun Lake was fully replenished was 2016, leaving it less able to meet a severe drought.