It’s perhaps the largest global cleanup initiative in human history, one that will eventually benefit the health of almost every living thing: ridding the world’s rivers and oceans of the discarded plastic that flows into the water at an ever-increasing rate.

Every day about 2,700 tons of plastic enters the ocean; much of that washes up on beaches, but a significant amount catches a ride on ocean currents and makes its way to the most remote spots on the planet. On its way it breaks into progressively smaller pieces until it becomes micro plastics which are ingested by many pelagic mammals, fish, and birds. And unless something drastic is done soon the scourge of plastic waste will begin to affect human health as it works its way into our food and drinking water.

Tackling the problem head on is The Ocean Cleanup, founded by wunderkind Dutchman Boyan Slat when he was just 18, with the Herculean goal of removing 90 per cent of floating plastic by 2040. “What’s going to happen over the next few decades,” he said at the IMarEST conference last year, “is if we don’t clean up what’s on the surface today all the plastics will sink down into the water column, which makes it more harmful, and then it’s much harder or impossible to clean up.”

After a series of frustrating setbacks where the first two pilot projects failed to properly collect trash on the open sea, The Ocean Cleanup went back to the drawing board and produced a redesigned System 002, dubbed, “Jenny,” and have had two dozen successful extractions of ocean plastic in which pieces as small as one centimeter were recovered.

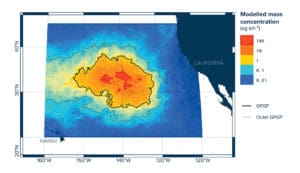

The primary objective is to clean the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a Texas-sized, circulating pile of floating trash between Hawaii and California, via a pair of slow-moving ships that tow a 1,700-foot long U-shaped barrier, collecting trash and funneling it to a retention zone. The slow movement of the ships allows marine life to avoid being trapped. The plastic is then sorted, returned to shore and processed into pelletized plastic for recycled goods such as sunglasses.

But will this make a true difference in solving the problem? A 2020 report by the Pew Charitable Trust compared the collection effort to mopping up a flooding house. “First you have to have to turn off the source of the water,” concluded the author, Yonathan Shiran, “then you wipe up the floor.” He was concerned that the cleanup efforts are a distraction from the real solution, “closing off the tap.” The correct action is to prevent plastic from entering the environment. Or better yet, for consumers to stop buying so much single-use plastic.

Recognizing the importance of a two-pronged approach The Ocean Cleanup is now removing this pollution from its source via eight autonomously operated solar powered collection vessels, called Interceptors, in rivers around Asia and the Caribbean. Using the river’s current, trash is funneled into a boom collector and scooped onto a conveyor for later removal. They hope to place these interceptors in 1,000 of the world’s most polluted rivers by 2025.

“We can do this if we just make the system bigger,” said an inveterately optimistic Slat. “And if we have 10 of them out there, we can clean up the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.”

For more info: www.theoceancleanup.com

Robert Beringer is a marine journalist/photographer, author of Water Power! For a sample go to: www.smashwords.com/books/view/542578.