Navigating the waters of the notorious Inside Passage, stretching between the San Juan Islands in northwest Washington State past Vancouver Island and on up to Alaska, is like finding your way through a tricky and dangerous labyrinth. Not for the weak of heart, you will encounter confusing tidal rapids that can run as strong as 12 to 16 knots replete with whirlpools that compete with those Odysseus faced in the Straits of Messina. The big difference is that the waters of the Inside Passage will also bless you with daily vistas of snow-capped mountain peaks on both the Vancouver Island and BC mainland sides. Combined with the myriad fjords, waterfalls and forest trails bedecked with salmon berries, grizzly bears and waters replete with wild salmon, urchins, crab and oysters, this stretch of water offers you and your crew some of the most awesome cruising territory on Earth.

During the winter of 2022, grimly facing another year of COVID, my son, Josh, his partner, Maria, and their seven-year-old son, Diego, announced that they were planning to sail their newly acquired 31-foot Australian-built Sapphire ocean-sailing sloop, Pax, up the Inside Passage with the hope of reaching Alaska. They had both negotiated sabbaticals that would allow them three months to accomplish their mission. For the first month or so they would be sailing with their friends, Luke, Amy, and their two-year-old daughter Ardea, on their similarly sized Pacific Seacraft Orion 27 cutter Seaweed.

The two crews decided they’d cast off on June 1. Maria and Diego would stay home for the first two weeks to wrap up the school year and job demands. I accepted Josh’s invitation to hop aboard and help navigate along the early stretches of this infamous body of water.

The last time Josh and I had done any distance together was when he and Luke joined me for the first leg of our Indian Ocean crossing in 2010. Now Josh was skipper and I was signing on as first mate. I coached myself from day one to follow his lead and not interfere with decision-making unless invited to. Despite my resolve, I frequently caught myself wanting to spout opinions. But the more I practiced self-discipline the more I enjoyed not being the buck-stops-here guy. Josh, Luke and Amy had done their homework, carefully plotting their intended route north through the many tidal “gates” they knew they’d be facing. There was little left for me to do except settle down and enjoy the ride.

Engine differences

The one big difference between their two boats was their diesel engines. Seaweed was equipped with a rugged, tried-and-true 27-horsepower Yanmar 3gm30f, compared with Pax’s little 1976 make-n-break Yanmar 12-horsepower YSB12. Josh’s old one-lunger — we called her Bessy — had challenged him from the beginning. He’d hoped to repower before heading north but ran out of time. He found a good diesel mechanic named Darrell Passmore at Fathom Marine in Anacortes. Darrell did everything he could to be sure the old girl was ready for the long haul but every time Josh went to start Bessy up, something didn’t function the way it should have. He spent several long days bashing his knuckles and cursing blue smoke as he tried to replace the exhaust manifold. He finally accomplished the job but was still trying to align its serpentine twists and turns, with Luke’s help, up to the moment we cast off.

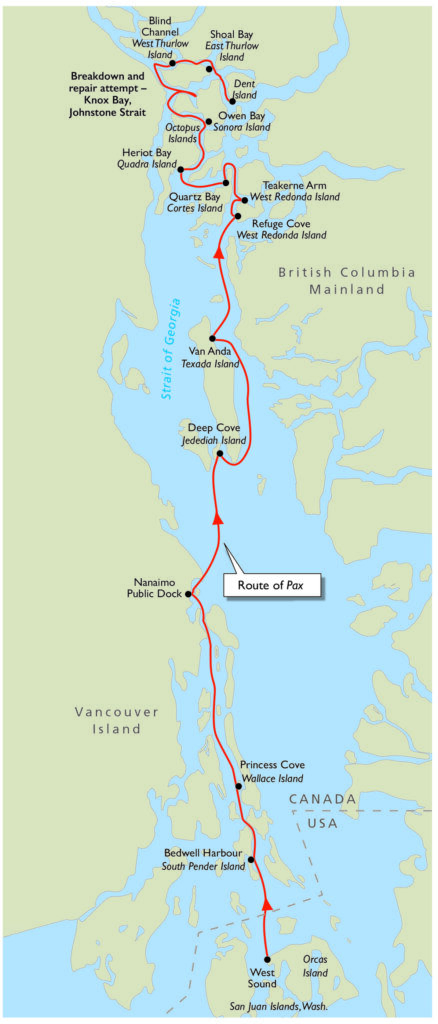

On a chilly Wednesday morning in June, 2022, we waved goodbye to Maria and Diego and Luke’s parents as they bid us smooth sailing. We motored most of the way to that imaginary red border line etched across our chart plotter and by mid-afternoon arrived at Poets Cove on Pender Island, our first landfall in British Columbia. The Canadian customs station there had opened for the season the day before. Good for us, since the next closest customs station was the much busier port of Sidney on Vancouver Island, a stop far west of our rhumb line. After several hours of nervously awaiting clearance, we celebrated permission to cruise Canadian waters for up to six months.

Early the next morning, we steamed out of Poets Cove and stopped for a night in the cozy anchorage at Princess Cove on Wallace Island, where we practiced our first stern-to anchoring. We shared this spot with only one other boat so early in the season.

Next, we headed toward our first “gate,” or tidal rapid, which we knew had to be precisely timed in order to avoid battling strong counter currents. Dodd Narrows, the gate just south of the busy port of Nanaimo, can run ferociously with currents up to nine knots. It’s a narrow passage making a nearly 90-degree turn between steep cliffs. Navigation is recommended only at slack water. Josh and Luke closely studied the tide charts and determined the best time to make the run but, because it was difficult to push Pax faster than four or five knots, we found ourselves running late. Via VHF the two captains discussed the pros and cons of riding with the gushing flood tide. Finally, the decision was made to go.

Running the gate

Seaweed led the way and we could see she was doing okay despite being shoved hard from side to side as she shot ahead. The Narrows were full of floating timber broken loose from rafts hauled by tugs through these waters en route to local mills. Entering the narrowest part of the cut, Josh went forward to point out sunken logs as he nervously watched them twisting and turning in the chaotic current. I was on the helm doing the best I could to dodge all the threatening driftwood as it corkscrewed toward us. We narrowly missed colliding with several gnarled tree limbs and deadheads. Holding our collective breath and gritting our teeth, we sluiced our way through and, after nearly an hour of hair-raising slaloming, we finally squeaked through the tightest spot. We breathed a little easier as the gut widened and the errant timbers began drifting further astern. Seaweed was well ahead.

An hour later, after securing a rain-soaked berth in Nanaimo, we were startled to see a fully-loaded container ship rapidly rounding the same gut we’d so recently escaped. We were grateful we’d not tried to squeeze through the slot in the same moment as that behemoth.

Departing Nanaimo, we swung northward preparing to cross the Strait of Georgia. This would be our longest open-water passage of the summer. We aimed straight for Jedediah Island sitting mid strait, tucked between Lasqueti and Texada islands. It was not a long sail but we carefully heeded the wind predictions in order to avoid a rough passage. The winds in the strait can quickly jump to 25 or 30 knots causing rough conditions, especially when the tide is running counter to the winds, but we were lucky. The breeze settled nicely between 15 and 20 knots and the waves were on our quarter. We had a lovely reach all the way up to Deep Bay on the northwest corner of Jedediah, a deep, secluded all-weather anchorage. Given how early we were in the season, we had no competition for the stern-tie chains strung along the rocky shoreline. We were still novices in the stern-to tie world but, with the new spooled line Josh had rigged on the aft rail, we quickly became facile running the dinghy ashore and stringing the warp through the ring at the end of the chain attached either to a tree or a ledge set just above the high tide line. A dozen or more boats can squeeze into this tiny cove using this arrangement. The trick is to set your anchor well as you back in to pick up the shoreside tether. If the cove is full and a strong squall comes through, you can end up with an anchor-dragging vessel-bashing tangle.

From Jedediah we made our way north to Texada and then West Redonda Island where we discovered Refuge Cove. If you’re looking for good fresh dockside water, fuel, ice, ship’s stores, hot showers and a comfortable berth for a couple of indulgent days, Refuge is your best bet. We did our laundry and chatted with the shopkeepers and dock attendants who were happy to welcome the first arrivals in what they hoped would be a busy summer after losing business during the pandemic. Refuge Cove is described as “whimsical yet functional.” I’d call it “funky.”

Not enough power

From Refuge we wound our way ever northward with stops at Teakerne Arm, where we explored the steep trails leading up and around the cascading waterfalls to the refreshing freshwater Cassel Lake, and then onward to delightful Quartz Bay on the northwest corner of Cortes Island. From Heriot Bay on Quadra Island, we aimed for the intoxicating Octopus Islands Marine Park. The only way in or out of this small piece of heaven is to negotiate one of three possible tidal gates: coming from the Strait of Georgia through Surge Narrows, from Discovery Passage, through the Upper and Lower Rapids of Okisollo Channels, and from the east through the Hole in the Wall. All three routes require careful timing. After an easy and uneventful passage through Surge Narrows, we successfully picked our path into Waiatt Bay via the rock-strewn southern passage but when it came time to leave the next day our timing was off by a half hour as we aimed through the Upper Rapids in Okisollo Channel. Even though we were just after slack tide, the current had already shifted against us and was building rapidly. As hard as we pushed against the seven- to nine-knot rapids, we could not beat them. We were forced to retreat. Seaweed had enough power to make it through, but turned back and we dropped hooks together for second idyllic night basking in the Octopus archipelago. The next morning, we timed our exit perfectly.

From the Octopus Isles, we sneaked into inviting Owen Bay on the northwest corner of Sonora Island. We anchored in the cozy cove just inside the entrance and hiked along dirt logging roads from the small settlement on the opposite shore up to high cliffs overlooking the Hole in the Wall Passage where we sat and watched boats fighting the currents from the east side into the Octopus Isles.

From Owen Bay we aimed for our next pit stop, Blind Channel on West Thurlow Island. This outpost is a full-service marina owned and operated by the Richter family since landing there in the 1970s aboard their own cruising sailboat. We wanted to stay longer, but reluctantly departed after one night. Our plan was to continue plodding our way north to the Broughton Islands where we hoped to organize a sea plane flight to ferry Maria and Diego direct to our anchorage.

Engine trouble

As we exited Mayne Passage and took the right turn into Johnstone Strait, Seaweed was again leading the way. We timed our escape perfectly riding the tidal currents and were chugging full steam ahead when a sudden sickening sound erupted from below. Bessy uttered a loud rattle and bang. We immediately throttled back to a crawl and I jumped below. As soon as I lifted the midship engine cover poisonous exhaust fumes poured into the cabin. I could see a bolt rattling loose from the exhaust manifold. I tried to snatch it but it fell into the bilge and disappeared beneath the engine block. Covering my face to avoid asphyxiation, I returned to the cockpit and urged Josh to turn into Knox Bay. A few minutes later we dropped the hook in 20 feet of water. Pax swung with the tide and settled gently against her chain lying about 30 feet off the muddy beach. We called Seaweed and she turned back and soon pulled alongside. With both engines shut down, we proceeded to search for the lost bolt. Luke, with his long arm, was eventually able to reach far enough into the bilge to fish out the escaped fastener. After careful analysis, we sadly realized we were facing more than just a bolt that had vibrated loose. It had sheared off and the stub end was stuck in the engine block. We managed to tighten down on the manifold creating one large hose clamp out of two. We knew this was a temporary fix, but we cranked old Bessy up, judged the exhaust fumes minimal and slowly crept back to Blind Channel where the dock crew we’d bid farewell to welcomed us again.

We immediately went to work trying to drill out the broken bolt from the block and luckily found a small extractor kit aboard one of the visiting power yachts. After hours of hard drilling, we eventually broke a heavy duty hardened-steel cobalt bit off flush with the hole in the broken bolt. The hole we hoped to attach the extractor to was now solid toughened steel that resisted everything we could throw at it. We borrowed a small blow torch from Stephen Dews, the owner of the newly-built Kiwi-bound schooner Wolfhound. While it was nice to meet Stephen, the renowned New Zealand marine artist, and his wife, Louise, the blow torch sadly made no difference.

Help from a pro

Finally, with our own resources exhausted, we reached out to Passage Marine in Campbell River. The owner, Chris Chambers, offered to jump aboard a water taxi with his tool kit. Forty-eight hours later he was alongside unloading boxes of heavy-duty wrenches and drills plus a portable electric welding set. He tried for several hours to bore a hole in the sunken bolt end so he could attach a more powerful extractor but finally gave up and brought the welder on board. He covered Pax’s main salon with flame-proof blankets and, with the steady hand of a heart surgeon, managed to delicately attach a new bolt head to the broken butt end and then, ever so gently, backed the culprit out of the hole. We cheered his patient skill over a cold Molson and I asked him what he planned to do if he hadn’t been able to extract the broken bit. “I guess I would’ve pulled the engine out of the boat and taken it back to my workbench in Campbell River!” As difficult as that sounds, the little Yanmar is so petite that he could well have succeeded with that last ditch approach. Fortunately, an engine-ectomy was not necessary and within an hour Chris had replaced all three fasteners and we had Bessy running again. Needless to say, we owed Chris and Passage Marine a huge literal and figurative debt.

Sadly, given the week we’d lost dealing with the manifold debacle, our plans to travel further north had to be adjusted. Maria and Diego were due to arrive in two days and there was no way we could make it to the Broughtons in time to fetch them. Josh rebooked their seaplane ride into the plush fishing resort at Dent Island just south of Blind Channel. After crossing through Dent Rapids we arrived at the dock and quickly got the sense that Pax and Seaweed were “poor cousins” surrounded by gigantic high-end powerboats but we were treated well and spent a lot of money for the privilege of visiting. Maria and Diego’s float plane landed literally at our stern and the two new crew stumbled happily on board. Within a week I had found my way to Campbell River and caught a flight home to Maine. Pax and Seaweed and their salty crews enjoyed another six weeks exploring Desolation Sound and then found their way back home to Orcas Island.

Although Pax did not reach Alaska in 2022, she ably carried her crew on their first adventure into the labyrinth of the Great Pacific Northwest. Queen Charlotte Sound, Haida Gwaii and Alaska will be waiting for another day. n

Nathaniel Warren-White is an actor, director and executive coach/management consultant. His book, In Slocum’s Wake chronicles his west-about circumnavigation, 2006-2011.