Like many cruisers hailing from ports on the west coast of North America, we’ve always had Japan on our minds as a natural leg of a Pacific voyage. We weren’t sure about an extended cruise, however. We had the impression that sailing in Japan was daunting — plagued by typhoons, currents, fog, fishing gear, forbidden ports, and impossible regulations. We had understood it was perhaps better visited by air and land than explored by sailboat.

The beauty of the culture and country aside, Japan is an undeniably convenient stepping-stone for completing a North Pacific loop. Because of prevailing winds and currents, a Pacific Ocean circuit would logically include Japan on the return to North America. Among those who have sailed there, Japan does get rave reviews. However, many of the people we knew who had sailed to Japan had stopped only briefly to reprovision for the jump across the North Pacific. They hadn’t seen it as a cruising destination in itself.

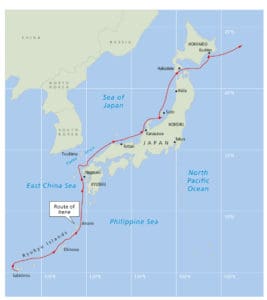

From March through May 2021, we had the opportunity to sail from Okinawa in the south up the west coast of the island chain to Hokkaido in the north aboard our 50-foot ketch Irene (a scaled-down Herreshoff Ticonderoga design). During this trip, we were surprised to learn that many of our preconceptions were false. The sailing was good, with predictable wind and many enchanting harbors and shelter was never far away in case of a blow or typhoon. Also, recent changes in rules and technology have helped with Japan’s unique challenges. Rather than daunted during our cruise, we were charmed, and we can recommend Japan as a cruising destination and so much more.

A typical day

We weren’t certain what to expect in Japan as we navigated complicated pre-departure paperwork. As with any new country, though, once we arrived and settled in, a daily routine became familiar.

This is what a typical cruising day was like for us: We depart at a time appropriate for the tidal current, just as we do in our home waters. Riding a fair current to the next stop makes sense, and if the day includes a transit through a pass, that timing is nonnegotiable. Arriving in the dark at an unfamiliar port has so many dangers that we try to avoid it. However, leaving in the dark is a different story since we’ve had a chance to see the layout of the port in daylight and spot unlit dangers, such as shallows, buoys, and snags. Accordingly, we tend to depart early, even before dawn if necessary, in order to arrive before sunset.

We sail to a waypoint in the next port recommended by a friendly Japanese sailor. We head directly offshore as we depart to make sure we don’t encounter any nets set inshore, then turn to the course for our destination. Our friendly sailor will have warned us about those nets with a dramatic admonition to steer way clear, yet he himself sails quite close to shore. Go figure. We have good winds, maybe a beam reach in winds of 10 to 15 knots with reasonable waves. Irene, like most boats, loves these conditions, and so do we. We fly onward, enjoy a lunch and maybe dinner on passage. The VHF radio is quiet, unless we are hailed by Coast Guard or customs stations. Local sailors don’t anchor and usually don’t use VHF radio. We sail with our AIS transmitting and thus attract attention from the authorities at a shore station or on a vessel. No matter. The conversations are polite and charming and always end with “Be safe!” and a warning to avoid surf, current, fishing nets, or weather. The miles roll by, and we approach our destination port, hopefully in daylight. Only once have we arrived in the dark — it worked out well, but who needs that stress?

As we approach, we are all business. This is when things can go wrong, so we consult our chart and get our plan together. Japanese ports are protected from storm waves by breakwaters — often multiple breakwaters — so you and your vessel will survive no matter the weather, but entering can be tricky, with doglegs and beacons. We weave our way in and enter a basin bordered by concrete walls. There is probably a fish co-op building, and perhaps an ice tower, as well as fishing boats tied up to the wall. We would never tie up in these busy spots, especially if the fleet is actively fishing. Instead, we make our way to the waypoint and tie up carefully.

As always, we ask the first person we see, “Are we okay here? Daijoubu?” These waypoints are valuable. We once tied up just a few feet from a waypoint we had been given and were directed to move the few feet back to be precisely on the waypoint. This speaks to a reality in Japan: If a boat, especially a foreign boat, shows up in an unusual place, people may be upset. Yet if you are in the spot previously occupied by a sailboat, it’s always okay. We’ve found that it is important to respond to instructions. If you are asked to move, do it! No big deal. Unresponsive foreigners in the harbor can be extremely disturbing in a Japanese village.

There may be some surge or waves from swell, tide, or traffic, and because the wall is made of concrete and equipped with bollards, spring lines and fenders are essential. We found our massive Yokohama-style fenders floating at sea and on the beach, and we’ll carry them on deck until we leave the country. It had been suggested that we need to carry a ladder in order to reach the top of quay walls, but Irene’s pin rail at the main shrouds provides a perfect step, and we get on and off the boat easily even at the lowest tides. The harbor scene is tranquil and attractive, with drying nets and colorful flags. We may take a walk away from the quay, admiring traditional houses and beautiful gardens, and perhaps a Shinto shrine or two.

Back at the boat, we may find a Japanese sailor who has tied up next to us or even rafted to us. We enjoy drinks and discussions, and the plan for the next few days becomes clear. We hear about the local onsen (bath) and about delicacies available at a nearby restaurant. Maybe we depart early the next morning, or perhaps another pleasant day or two passes before we move on. Cruising at its best! Mixed among the fishing ports, which are free of charge, is a larger city with a marina, where we pay a fee similar to that charged by marinas everywhere. There are also free (or very inexpensive) pontoon floats available in smaller tourist towns.

A bit of history

The classification of “closed” and “open” ports dates to Japan’s isolationist period from the mid-17th to mid-19th centuries, a response to problems encountered with unregulated trade and interaction with Western nations. Foreign ships were only allowed to arrive in certain “open” ports. The requirement remains to this day: A visiting foreign yacht is normally only allowed to enter “open” ports, which tend to be larger commercial ports — fine as a base for inland travel, but not as scenic, enjoyable, or representative of the diversity of coastal Japan as the smaller “closed” ports.

Luckily, in recent years the Japanese government has streamlined the process (it’s always a process!) With a closed-port permit obtained on entry, a foreign yacht may visit small, charming, ordinarily closed ports throughout Japan. Amazingly, this permit has no expiration date, so as of this writing we never need apply again should we return to Japan aboard Irene. This is good news given that Japan has hundreds of ports that are often adjacent to charming and scenic villages.

We were granted our closed-port permit from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism after several email exchanges before our arrival in Japan and a bit of back and forth due to COVID-19. In our three months of cruising, we were never charged a single yen to tie up for as many as several nights in these small harbors. We were only charged moorage at the occasional marina (two in Okinawa and one in Fukuoka) that we visited when we needed to empty garbage and top off our water tanks.

A Naikosen permit also facilitates cruising. This form documents a temporary import of the vessel to Japan. Once imported, the vessel is considered domestic rather than foreign for all customs issues. This allows travel from port to port without going through customs inspections each time. A very useful form indeed.

We had read and heard that “knowing some Japanese” was needed. Ha! It’s impossible for most of us to pick up any new language to fluency while transiting a country for three months, much less such a complex one. Of course, we picked up some important words to be polite and communicate a few common things, but grammar and proper conjugation were definitely beyond our capabilities. Fortunately, smartphones can now read Japanese characters, and this convenience is amazing!

Many government offices had someone who spoke English, and the young were often fluent, a result of their foreign language curriculum. Necessary telephone calls with officials were completed by asking the receptionist if they spoke English. Invariably they would transfer the call to a specialist in their office. Often a shy Japanese person would answer “no” when asked directly if they spoke English. In that case, Peter sometimes would jokingly say, “No problem, I speak Japanese. Ichi, ni, san, shi, go.” Counting on his fingers like a preschooler got a giggle, and often it turned out that the person had understated their English proficiency. There was always enough understood to solve whatever issue arose.

There is a small but enthusiastic (and very helpful) group of Japanese yachtsmen who make arriving in small ports — the very places we want to visit — simpler. They share information and waypoints generously. Waypoints are a key to successfully cruising Japan — they’re literally like having a key to a port. One of the many pleasures of cruising in the country is greeting and chatting with fellow sailors. Expect to get excellent advice on exploring any section of coast, where to dine, and dangers to avoid. Also, many ports have a resident yachtsman “ambassador” who assists in multiple ways — communication with officials, provisioning advice, route planning, and so on. These people are known by word-of-mouth. As an example, we had a sail shipped to a cruising ambassador in Hokkaido, where it was conveniently waiting when we arrived.

Favorites

The onsen, or public bath, is a wonderful place to relax and warm up after a chilly day of sailing. Many have a “family room” that can be rented for a private bath, which we preferred, not only because of COVID-19 concerns but also because we didn’t want to accidentally break any rules of etiquette. For example, we have some discrete sailor’s tattoos that would be strictly forbidden in a conservative onsen.

Japanese laundromats are efficient and spotlessly clean, and there are several to choose from in town. They sported the best machines we’ve encountered anywhere in the world! Many newer machines wash, dry, and include soap. Just load the clothes, pay, and come back in an hour for clean, dry clothes. Some of the laundromats were attended, usually by charming mature ladies. Our smartphones translated the instructions at the unattended laundromats.

The culture of Japan is world-renowned. All of our expectations were met and often surpassed in hospitality, visual delights, and art of all types — culinary, industrial, architectural, horticultural, design, and public art. We were especially enamored of the culture of hospitality. Many people — officials, shopkeepers, fishermen, and bystanders — were willing to try to resolve any sort of problem we had, and many offered friendship. Unlike those in some parts of the world, government officials in particular seemed to want to help, even when a situation seemed unsolvable. We found that, in general, the Japanese people genuinely wanted to make a visitor’s experience positive.

Unusual aspects for cruisers

Anchoring is only strictly forbidden in any port or near aquaculture. In the rest of Japan it’s just not done. If one anchors, it is best done off the beaten track. Otherwise, it may be assumed that help is needed or your actions could cause alarm with the local population.

We had expected to encounter officialdom — everything we had read prepared us. And in fact, when we arrived at our first port in Japan and tied up, we were greeted by carloads of uniformed officials — customs, immigration, health, and Coast Guard. They coordinated with one another quite well, with one team waiting while another finished its business, but even so, at one point there were a dozen officers aboard Irene carefully taking swabs from every imaginable surface.

What we had not expected was continued oversight from the Coast Guard and immigration, even with our imported-boat and closed-port entry permits. When we arrived at some of our destinations, Coast Guard officers would appear with forms to fill out — last port, next port — and, sometimes, a request to inspect down below. At first we were disconcerted, but we came to understand the expectations and even enjoy the interactions. The officers were always young, polite, earnest, and friendly. For many of these coastguardsmen, ours was the first yacht they had seen in their official capacity.

Storms, nets, traffic, seaweed, fog, currents

Japanese waters were not the most difficult we have navigated over the years by any means. The ports are well buoyed and lighted, and the coast doesn’t have many off-lying dangers.

The southern islands do have plenty of coral, and all the normal cautions apply regarding careful piloting to avoid it. The northern islands have seaweed, current, fog, and small freighter and fishing boat traffic. This is no more difficult than those same challenges sailors experience in the Pacific Northwest. The shipping traffic we encountered behaved in courteous and predictable ways. Interestingly, VHF radio is not normally used in passing situations.

Japan is well surveyed and charted. Our Navionics and C-MAP charts were good offshore, but many small ports were not charted in any detail. There is detailed Japanese charting available for all ports online and in regional booklets (S-Guide) now out of print, but we were loaned a copy by a sailor we met along the way. The Japan Hydrographic Association has an app (Apple only) that is reasonably priced and updated regularly, which includes fishing net permit locations, depths in harbors, and notices to mariners. The only catch is that it’s in Japanese — of course. The handy translate feature on the smartphone helps decode the details.

Cruising under sail in Japan is enjoyable, predictable, social, and rewarding. We now know that Japan is very much worthy of repeat visits and detailed explorations rather than just a way station on the sail home.

There are no current published cruising guides for Japan. We used a number of online resources in addition to helpful information acquired along the way. We’ve documented more details of our various travels on our blog at oceanswell.blogspot.com. n

This article originally appeared in the Cruising Club of America’s publication Voyages.

Peter and Ginger Niemann are liveaboard voyagers on their 50-foot ketch Irene and are member of the CCA’s Pacific Northwest station.