Editor’s note: This is the fourth and final installment in a multipart series, “The toughest passages of 50,000 miles,” a look at the most difficult aspects of circumnavigators Ellen and Seth Leonard’s various ocean voyages. In this last piece, Ellen changes the focus.

Earlier in this series, I reflected on some of the toughest times in my 13 years of ocean voyaging. Happily, however, there have been far more wonderful moments than bad ones in that time; this is probably obvious, or I would have stopped voyaging!

It’s hard to pick my favorite moment ever. Was it my first ocean crossing, when I discovered that the reality of my childhood dream was even better than my expectation of it? Was it meandering through the beautiful South Pacific islands? Or voyaging through the wilderness waters of Alaska? Or maybe it’s been making friends with so many of my fellow sailors from around the world.

|

|

Ellen Massey Leonard at the wheel of Heretic. |

In keeping with this series, though, I thought about my best passages ever. The one that came immediately to mind was crossing the Atlantic in April 2010.

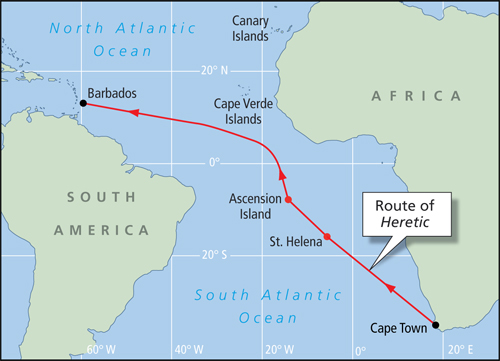

My husband, Seth, and I made this crossing at the end of our global circumnavigation, so we were coming from South Africa. Considering that this passage came almost on the heels of one of our most difficult passages ever (see “Worst weather challenges,” September/October 2019, Issue 257), it was doubly welcome. The first two legs of our Atlantic crossing were fine but not our best ever. We left Cape Town at the end of February for the British overseas territory of St. Helena island, an extinct volcano known for being the site of Napoleon’s exile. We covered the 1,700 miles in 15 days, not especially fast but quite comfortable. The cloudy skies throughout the passage were a bit of a drain on both our spirits and our battery bank (the solar panels had trouble keeping up), but we certainly couldn’t complain after the high winds and seas we’d had en route to Cape Town.

After a perfect idyll of a week hiking all over St. Helena — a week that was yet another of my favorite moments in my voyaging — we set off for Ascension Island, 700 nautical miles to the northwest and part of the same territory. Unlike our cool, overcast, sedate and steady passage from Cape Town, this one brought hot and humid tropical conditions, worsened by hatches battened down in the face of constant rain squalls. It felt like we were in the Intertropical Convergence Zone (“the doldrums”) already, despite the fact that the weather charts showed it further north and west. Seth and I were both pleased when the red volcanic cone of Ascension appeared above the horizon.

|

|

Heretic’s route from Cape Town to Barbados. Ellen and Seth sailed on a more northerly course after Ascension Island to avoid the Intertropical Convergence Zone off Brazil. |

First impressions change

At first glance, Ascension seems a barren, desolate place with little to recommend it. A tiny village huddles on the leeward shore where swells break clean over the jetty, and the red and black igneous rock has yet to be covered in much vegetation. The impression was only strengthened upon going ashore, after we had overcome the treacherous jetty. The dusty 600-person town was almost silent in the hot stillness, and the tiny store had — understandably, considering the remoteness of the place — only a couple of wilted cabbages in the produce bins. Our hearts sank, thinking of the month-long ocean crossing ahead of us with no fresh fruit or vegetables even to start off with. Adding insult to injury was the £60 entry fee, especially as we’re not really the sort to care that much about rare passport stamps.

It didn’t take long, however, for our first impressions to be proven wrong. We went for a long, hot walk along empty roads through red earth and scrub bushes, and were feeling simultaneously irritable and virtuous when we crested a ridge and there lay Wideawake Airfield and the Royal Air Force base. Just a little further on we came to the U.S. Air Force base with its red dirt baseball field, appropriately named Moon Valley Stadium. We turned in toward the bar and diner that was open to the public and came up short: After over two years of voyaging without a visit home, all of a sudden we were back in the U.S. Everything about the diner, from the food and beer to the napkin dispensers, was exactly like a diner back home. We both ordered heaping chef’s salads (an American dish we hadn’t seen in years), wondering how this abundance of delicious lettuce and tomatoes had come here. The answer was obvious: It came on the weekly military flight and was only available on the base.

|

|

Sweeping views seen while hiking on St. Helena. |

Fish and turtles abound

The next few days that we passed on Ascension turned out to be almost as wonderful as our days on St. Helena. We went scuba diving off our 1968 cutter, Heretic, and were met with a cloud of black durgons, turtles, eels, and countless other fish and reef creatures. With no barrier reef and almost no rainfall and thus no runoff, the water was as clear and blue as the open ocean. Indeed, one day we spotted a pelagic fish — a mahi-mahi — right off our stern.

Our forays ashore were also much better than we first expected, and not just because of the chef’s salads at the base. Ascension has a large population of nesting green turtles, which we literally almost stumbled on during an evening walk along the beach at the head of the anchorage. Big mother turtles were making their way out of the surf and up the sand to dig nests for their eggs. Walking up to a seemingly empty mound, we discovered tiny baby turtles right in the act of hatching and scurrying out of their sandy pit to run for the ocean. The whole experience was magical: the tiny turtles, the crashing surf and the moonlight bathing everything in its silver glow.

One isn’t allowed much time on Ascension as a foreign tourist (or at least that was the case in 2010), so Seth and I were soon preparing to leave. After clearing out with the British officials, and on our way back to our dinghy, we ran into an officer we’d met at the U.S. base. He stopped his truck and, after a few minutes’ chat, handed us a big bag filled with huge juicy oranges and apples. They’d just come in on the flight from Miami, he told us — fresh Florida oranges. We were thrilled; now we’d have fruit to keep up our morale on our upcoming 3,000-mile passage to Barbados and the Caribbean.

|

|

A cloud-shrouded landfall. |

Seth and I had been careful to study the weather charts and radar pictures for the passage before leaving Ascension, and we had decided on a longer, more circuitous route in order to avoid the worst of the doldrums. A heavy, nasty belt of calms, squalls, thunderstorms and rain appeared to be piled up on Brazil, which is no doubt the usual state of affairs given the ecology of the Amazon basin. On the weather charts, it gradually tapered to the east until there was almost no sign of that kind of ITCZ weather over by West Africa.

Seth and I are always keen to avoid thunderstorms (see “Dodging lightning,” January/February 2020, Issue 259), and we also like to avoid calms so that we can sail as much as possible. We simply like to sail; it’s why we got into voyaging in the first place. Aboard this first boat of ours, Heretic, we had thus far managed to sail almost the entirety of our circumnavigation. We had never bought more than 40 gallons of diesel in an entire year. Our desire to sail was compounded by the fact that we did not have an autopilot. Steering a motoring sailboat is a very tedious chore, especially on an overcast night when your only means of staying on course is close attention to the compass in its little red pool of light.

So, we plotted a course across the Atlantic by which we would best avoid the ITCZ. It would add 200 nautical miles to the great circle route, but we trusted that it would make for a more pleasant passage and possibly also for a faster one.

|

|

|

|

Ellen and a noddy share a moment. |

A newly hatched baby turtle heads seaward on Ascension Island. |

Indeed, it turned out to be our best passage ever.

Leaving Ascension Island in our wake, we steered a course due north. Our plan was to continue on this course until we reached the northeast trade winds, whereupon we would turn west for Barbados. Heretic wafted along on a reach under her genoa, staysail and single-reefed main — the reef necessary only to better balance our Aries wind vane. The weather was hot and clear, and as soon as the island sank astern, we were back in our pelagic world of blue sky and sea, dotted with just a few friendly, puffy clouds.

Offshore routine

Day after day we continued this way, settling easily into our routine of four- and six-hour watches. My 0000-to-0400 watch saw a moderate but pleasant wind increase each night and it became my favorite time of day, when the tropical heat finally cooled and I could marvel at the great dome of stars overhead. The only four hours we spent together — from 1000 to 1400 — were, of course, the hottest of the day, when we alternately tried to hide from the burning sun in what little shade there was, or doused ourselves over and over again with buckets of seawater, which was never as cool and refreshing as we would have liked.

|

|

The Leonards enjoyed beautiful sunsets on a benevolent Atlantic. |

We were approaching the equator from the south just after the March equinox, and so the geographical position of the sun was directly overhead for at least one of the days of our crossing. It’s a strange thing not to have a shadow at all at midday, but I almost didn’t notice it on account of the extreme heat. I’d never experienced anything like it. Those oranges from the U.S. military flight tasted just wonderful.

Aside from the heat, however, the crossing was perfect. It was so perfect we got bored. For over a week, we didn’t have to touch a sail; the southeast trades pushed us north with perfect regularity. We marked our position on the chart, watched the flying fish, cooked meals, bathed in seawater buckets and read our books over again. This was our second time through the collection of books with which we’d restocked our library in Cape Town.

About 200 miles north of the equator, the wind shifted. The sky, however, remained clear on all sides. We went about adjusting our sails for headwinds and continued on course to the north as close as we could point it. The lack of wind waves indicated that these headwinds probably did not have long fetch and could be short-lived. But we were nonetheless a little nervous that they heralded the doldrums we had hoped to avoid. Heretic steered herself north in the refreshingly cooler wind for about 24 hours, when the wind gradually began to veer into the northeast.

|

|

A noddy resting on Heretic’s radome. |

Seth and I couldn’t quite believe it, but after another full day of steady northeast wind, it really and truly seemed as if we’d sailed right from the southern trade winds to the northern ones. We’d encountered no ITCZ at all. We could spin the helm and run down to Barbados.

Birds join the crew

The next two and a half weeks as we sailed west-northwest were almost a mirror of our first week and a half. We hardly touched a sail. It grew less hot as the days went on, and we marked each 500 miles with a little treat, usually one of the candy bars we’d bought at the tiny store on Ascension. We watched the bird life, especially enjoying two little noddies that came to rest aboard Heretic. One of them proved nearly impossible to dislodge from his perch on our (nonfunctioning) radar, and the other alighted on the main sheet and seemed unconcerned by my presence right next to him in the cockpit.

Twenty-six days after leaving Ascension, we sighted the low mound of Barbados. We passed a few fishing boats and then some day-tripper tourist catamarans as we sailed around the southern tip of the island and up to the port of entry at Bridgetown. Culture shock set in as soon as we entered the harbor, a big ship terminal that felt tiny after a month on the open ocean and which was dominated by an enormous cruise ship. We soon had Heretic safely tied up to the wharf and were setting off across the baking concrete pier to the Customs and Immigration office. With passports stamped and the unique trident flag of Barbados flying from Heretic’s starboard spreaders, we were free to look around and contemplate the passage we’d just completed.

|

|

Culture shock on arrival in Bridgetown, Barbados: Heretic dwarfed by a cruise ship. |

We’d had a perfect trip. We couldn’t have asked for more settled weather, steadier winds, kindlier seas or sunnier skies. We’d enjoyed a month at sea better than any we’d had before, with only a few squalls and some strong sun and heat to mar it. In reaching Barbados, we had very nearly completed our circumnavigation. We were only 24 and 27 years old and had made the voyage on very little money in a very rudimentary boat. We had a lot to be proud of and a lot to be thankful for. A friend of ours, whom we’d met at the very beginning of our four-year voyage when we were still in the throes of our steep learning curve, wrote to congratulate us, mentioning offhand that he’d never quite believed we’d actually make it. Thinking back to those beginnings, it seemed a wonderful achievement to us, too.

And yet we were strangely sad. It was partly the cruise ship terminal where we were moored. After a month at sea, amid the wilderness of the ocean, it was an abrupt change — and to us, not a good one — to be surrounded by man-made structures and thousands of people. It was partly the disappointment of finding no fellow sailors in the harbor with whom to talk about the crossing over celebratory beers. But mostly, it was the knowledge that this voyage that had meant so much to both of us was coming to an end. We didn’t know then that we would find a way to keep voyaging, and that we in fact had many more wonderful — and challenging — sailing experiences still ahead of us.

Contributing editor and circumnavigator Ellen Massey Leonard and her husband, Seth, won the Cruising Club of America’s 2018 Young Voyagers Award.