Editor’s note: This is the first part of a multipart series, “The toughest passages of 50,000 miles,” a look at the most difficult aspects of circumnavigators Ellen and Seth Leonard’s various ocean sailing trips.

Last summer, in the middle of our second Pacific Ocean crossing, my husband, Seth, and I realized that we had sailed 50,000 sea miles. Had conditions been favorable, we might have celebrated with a nice dinner or maybe even a glass of bubbly. As it was, reefed down hard with 25 knots and 8-foot seas on the nose, we toasted our accumulated mileage with orange juice.

We undertook this crossing, from Mexico’s Cabo San Lucas to French Polynesia’s Marquesas Islands, very late in the season. Consequently, we encountered these southerly — even southwesterly — headwinds rather than a smooth, downwind run. We were disappointed and fatigued by the endless pitching and rolling. But it could always be worse, we kept reminding ourselves. Indeed, it had been worse quite a few times before.

This thought led us to try and rank our all-time worst passages. In what category, though? Worst weather ever? Worst prolonged weather? Worst in terms of breakages? Most tedious passage?

|

|

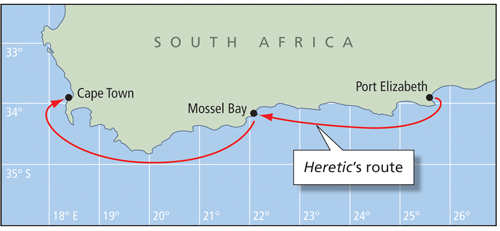

On Ellen and Seth Leonard’s circumnavigation, they sailed on their 38-foot cutter Heretic. Their route from Port Elizabeth to Cape Town took them through notoriously storm-tossed waters. |

Then, of course, there’s the fact that all sailors are optimists (or the idea of bouncing around the vast ocean on a small boat wouldn’t appeal in the first place), and so all these “worsts” have silver linings. The worst weather ones, provided both you and the boat survive intact, leave you with an uplifting sense of accomplishment. So do the worst breakage ones. Even the most tedious ones have the silver lining of being boring, which is always preferable to terrifying.

The worst weather passages were easy to choose. Seth and I were unanimous in remembering both our 20-day passage from the Arctic to the Aleutian Islands of Alaska, and our rounding of Cape Agulhas, the southernmost point of Africa.

Topography and currents

The waters around Cape Agulhas are made treacherous by three converging factors. The topography of the seabed is one: The Agulhas Bank, a wide section of the African continental shelf, extends 140 nautical miles south of the cape with depths sloping gradually from 100 to 600 feet before dropping sharply to the abyssal plain. Its effect is similar, though less dramatic, to the Drake Passage where the Andes submerge to create a ridge where the great unbroken swells of the Southern Ocean can rear up into breakers.

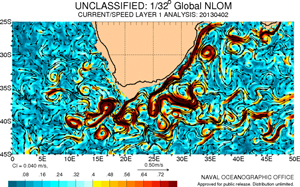

Another factor is the oceanography. Two strong currents meet in swirling eddies over the bank: the cold, north-flowing Benguela Current that runs up the west coast of Africa and the warm, fast, high-volume Agulhas Current flowing south down the east coast. Together they create strange disturbances in the water, adding to a potentially confused and dangerous sea state.

|

|

The strong currents and eddies off Cape Agulhas add to the difficulties of bad weather off South Africa. |

Finally, there’s the weather. The gales that sweep up from the southwest against the Agulhas Current are lessened but not absent in the austral summer, when most bluewater voyagers sail South African waters. Added to this is a phenomenon known in Cape Town as the “Cape Doctor” (because it clears out air pollution): short-lived but severe easterly winds caused by localized coastal low-pressure systems. These shallow sou’easters (“shallow” because of their low depth of about 1 km) generate wind speeds of between 48 and 80 knots, or Force 10 to 12.

Seth and I encountered one of these. It was not in any of our forecasts, and we were already fatigued before it happened.

Shredded mainsail

Our 185-nm hop from Port Elizabeth to Mossel Bay had ended in a gale that destroyed our mainsail, tearing the fabric to shreds. But rather than being able to rest after this ordeal in the sheltered harbor, Seth and I spent the night at anchor in the open bay — all the transient slips were taken — rolling in heavy swells. The forecast for the following few days predicted moderate easterlies; no big deal on their own, but they would turn Mossel Bay into a lee shore and thus even more uncomfortable. Moderate easterlies were perfect for heading west to Cape Town, however. So we weighed anchor after bending on our spare mainsail.

At first all was well, perfect wind to scoot us along under single-reefed main and genoa. After dark on the second day, though, the wind blew up very strong, very suddenly. We hoisted our tiny 10-ounce blade staysail and doused everything else.

|

|

The route of Celeste through the Chukchi and Bering Seas to Dutch Harbor. |

Not predicted in any of the forecasts, this was a shallow sou’easter of the first order. Years later, Seth and I saw video footage of the 1979 Fastnet Race and we both simultaneously said, “Hey, that looks like South Africa.”

We had been sailing the rhumb line since the weather was so good, which had brought us right over the Agulhas Bank. In no time, the waves were towering over Heretic, the 1968 cutter that we owned at the time. She was a solid fiberglass boat with a heavy displacement of 24,000 pounds and only 27 feet of waterline. The waves were breaking — and she was surfing down them.

Many of the combers broke clean across her deck and coach roof, drenching the two of us in the cockpit and filling it almost to the coamings. At the beginning of the storm — for a storm this definitely was, not a gale — one wave poured right into the cabin, filling Heretic’s very deep bilge and more until the floorboards floated. This happened immediately after I had struggled up on deck and before I could get the companionway hatch completely closed up. I fitted in the last hatch board and went to work on the manual bilge pump mounted in the cockpit until it sucked dry. Seth kept steering; he was concentrating hard on keeping Heretic from slewing broadside to the breakers.

Drogue unavailable

The storm had blown up so quickly that it was all we could do. The drogue was stowed away in the lazarette, a complacency (due to the benign forecast) that we bitterly regretted. Opening the big lazarette hatch would guarantee even more water filling the boat than had already happened. After Heretic’s frightening sluggishness after the wave that had poured into the cabin, it was not a risk we wanted to take. And once her bilge was pumped, Heretic was doing all right again, shaking off the water that broke over her and rising to each new crest. We just needed to keep her from broaching broadside, which we knew would mean capsizing. And we needed to keep her bow from nosediving into the troughs, which could potentially mean pitchpoling.

Despite the severe wind, a sustained 50 to 55 knots frequently gusting above 60, the sky was mostly clear and a low setting moon cast a pale light over the roiling white sea. I had never seen the ocean all white like that, the spray from the breaking waves blowing horizontal. About four hours into the storm, around 01:00, in starlit darkness, we sighted a large bulk carrier fairly close and on an easterly course. She was bucking the waves, and green water was breaking clear over her bow and running down her deck. Given the freeboard of cargo ships, her bow was 35 to 40 feet tall, which meant the waves really were 40 feet, not the “40-foot waves” of tall tales told in seaside pubs all around the world.

|

|

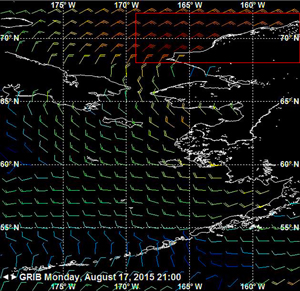

This grib file shows high winds encountered in the Chukchi Sea. |

An hour later, our heavy staysail blew out in a section along the luff. Neither of us wanted to go forward to douse it (it’s hank-on, not roller-furling) given all the waves that were breaking over the deck, so we just left it there — it was still attached in most places anyway. We kept steering, drenched and shivering but fired with adrenaline.

Daylight finally came. It was almost worse because we could fully see how tall, steep and breaking the waves were. Seth later told me that standing in the companionway, looking aft at me steering, he could see the tops of the waves far, far above me. When he took over again, I saw the same thing but also didn’t mention it then.

Fifteen hours in, a thick cloud bank appeared, the most defined I’d ever seen, like it had been drawn with a ruler. It went south from the Cape of Good Hope, and we both wondered aloud, with not a little fear, what it could mean — yet worse weather?

An hour later, we were under it. The wind died suddenly and completely. It was over. The waves were still high and confused, so we started the engine to keep steerage. Thankfully the batteries had not been damaged when the wave filled the cabin, and the old Yanmar turned over. After an hour or two, the waves lay down. Eventually we were motoring north to Cape Town in a sunny dead calm. That evening, we watched the sunset glow on Table Mountain, wreathed in wisps of fog, and I scrounged around for our camera, remembering it for the first time in what felt like much longer than 24 hours. By midnight, we had maneuvered into a free slip at the Royal Cape Yacht Club and were opening a bottle of champagne.

The storm didn’t last long, only 16 hours. If we’d had to spend many more hours at the wheel, the increasing fatigue would have made it harder and harder to sustain our concentration on keeping Heretic at the correct angle to the waves.

|

|

Ellen bundled up on watch during the Arctic passage from Point Barrow, or Nuvuk, to the Aleutian Islands. |

Autumn comes quickly

August is already autumn in the Arctic. Gone is the midnight sun. Instead the nights get longer rapidly, and by the end of the month there are over eight hours between sunset and sunrise. At Point Barrow, Alaska, migratory birds, already molting into winter plumage, mass into huge flocks to begin their journey south. Point Barrow is at 71° 23’ 20” N. By September, the sea ice to the north is expanding again; the freeze-up has begun.

It was mid-August when Seth and I left Point Barrow for Dutch Harbor in the Aleutian Islands, about 1,200 nautical miles south on the most direct route. We had spent two weeks there exploring the region. We had also been watching the weather for a window to start sailing south. None had come. Never did we have a long enough spell of northerly wind to push us to the next possible anchorage. It doesn’t help that Alaska’s Arctic coast is shallow and exposed pretty much all the way from the top of the North Slope through the Bering Strait, after which you finally come to Nome and its man-made harbor.

Finally, with the forecast of freezing spray becoming unpleasantly repetitive, we headed out. The wind was from the southwest — dead ahead — but was predicted to clock around to the northwest. For five hours, we made a long tack west followed by a long tack southeast. After 10 hours, we made landfall again … in exactly the same place. The north-setting current had done us. We gave up and returned to anchor and sleep.

An ominous sky overhung the Beaufort Sea when we raised sail again that evening. But the wind was now in the west so that we could point our course, even if we were close-hauled. It was a bone-cold, dark and nauseating beginning to the passage, with Celeste bucking the steep chop of the shallow Chukchi Sea.

|

|

Seth staying warm in the companionway of Celeste while on evening watch in the Bering Sea. |

The forecasts are good in Alaska, so the wind did indeed come into the northwest and then the north, so that we were running fast before it. It also built to exactly the predicted 30 to 35 knots. Spray flew off the crests. Fortunately, however, the air and water temperatures were not so cold that the seas we shipped had hardened into ice.

Celeste, our cold-molded wooden cutter that we currently own and on which we were making this voyage, is lighter displacement than her predecessor, Heretic. With a foot more waterline (28 feet) and 17,500 pounds displacement instead of 24,000, she is a livelier ride (read: more nauseating) than Heretic, but faster and drier. I’m not sure what it is about her design, but she also loves strong winds. Above 20 knots and she drives forward, her rolling motion smoother, but the acceleration down each wave is not necessarily the happiest experience for her sailors.

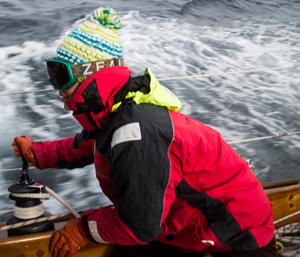

Tumbling gray-green waves

For the next four days, the whole of our world was the gray sky and white-crested gray-green waves of the Chukchi Sea tumbling under wild winds. Celeste tore before them under jib and staysail, the wind vane keeping her on course. Seth and I stood our four-hour watches in the raw cold of the Arctic autumn, huddled in foul weather gear and many layers of down and wool. Celeste, while an eminently seaworthy craft, is not a purpose-built high-latitude boat; she has no pilothouse from which the watchkeeper can steer, navigate or keep a look out while staying warm. We have only a canvas dodger to keep out the wet but not the cold.

The waves built higher with each day of high winds until Celeste’s stern was rising to 16-foot waves and sliding fast down their faces. Neither of us was worried, though. She was “happy,” if you’ll forgive the anthropomorphism. The waves were white-capped but not breaking; everything was fine, just not comfortable.

The Bering Strait — a waterway of strong currents, shallow depths and high winds — in fact gave us a brief respite of slackened wind and calmer seas. The clouds lifted to reveal the two Diomede Islands (one American, one Russian) and Cape Prince of Wales, the westernmost point of mainland America.

|

|

Seth ashore with Celeste at anchor on Alaska’s northern coast. |

The reprieve was short-lived. By nightfall, the beginning of day five of the passage, the wind was up again, just as strong and this time from the west, beam-on to our course. The seas built quickly and steeply in the shallow Bering Sea and we were rolling in a newly uncomfortable motion. That kept up for another full day until the wind backed right into the south, dead against us, without slackening. We hove-to west of St. Lawrence Island and took turns resting while Celeste slipped slowly northeast for 36 hours. It wasn’t worth the strain on either us or the boat to fight the contrary winds.

The grib files weren’t heartening: one day of west wind, followed by more 30- to 35-knot southerlies predicted to last at least five days. Seth and I had hoped to make it a nonstop passage from Point Barrow to Dutch Harbor, but it was clear that we’d either have to heave-to again or find a place to anchor. Fortunately, Nunivak Island was a day’s sail away; we could reach it before the next southerly gale.

Day eight saw us rolling along in the strong westerlies, our course altered slightly for a broad bay on Nunivak’s north shore. We made landfall before dark the next night and got our anchor holding just as the southerlies began.

Standing anchor watch

Over the night and the next day, the wind built until it was churning the shallow bay into whitecaps. Celeste was hobby-horsing in the chop and sailing around on her chain, pulling at the bridle. It was time for anchor watches. We checked the chafe gear. We listened to the rain beat the decks while we stared at the GPS, making sure we weren’t dragging. We stood on deck and looked at the shore, again making sure we weren’t dragging. A few loons appeared in winter plumage, reminding us yet again that sailing season was over in the Bering Sea.

We never went ashore. It was never safe enough, either to leave the boat or to launch the dinghy. The wind was blowing too strong out to sea.

|

|

Nunivak Island anchorage seen out a porthole. |

Finally we got a forecast other than 40-knot southerlies. We’d have southwest 25 building to northwest 35, and then finally diminishing to north 15 before another southerly gale. We decided to leave as soon as it was southwest. If lucky, we’d make it to Dutch Harbor before the next southerlies.

It worked. We beat west with the lee rail buried for about a day before bearing off south and roaring before strong winds for another day. Then the wind tapered to beautiful weather, the first we’d had in months. We sailed off the continental shelf into deep water, also for the first time in months. The change in the sea state was noticeable: The waves grew long, an enormous relief after the steep short-period seas we’d started to think were normal. Almost as if to welcome us back to more pleasant climes, two huge fin whales surfaced next to us.

That evening, we sighted glaciated Shishaldin Volcano in the Aleutians, 75 miles away. By morning, we were closing with Unalaska Island and sailing past mats of giant kelp. Including the false start from Point Barrow and our days standing anchor watches, we had been at sea — without going ashore — for 20 days.

That night, docked in Dutch Harbor, we could smell the land. Maybe because of the smells, or the still water, the green tundra-covered mountains, or the 50° F air (warm compared to the Arctic), Seth and I kept saying how much it reminded us of the South Pacific. In reality, the Aleutians are a rugged, high-latitude archipelago inundated with ferocious storms and winter snows. They are within the 10° C summer isotherm (where average summer temperatures don’t exceed 10° C), one of the three definitions of Arctic (the others being timberline and the Arctic Circle). So the fact that we were sitting out in the cockpit, reveling in the warmth and calm, was a testament to our shifted baseline, to just how demanding the passage had been and how accustomed we’d grown to those conditions.

Ellen Massey Leonard and her husband, Seth, completed a circumnavigation aboard their 38-foot cutter-rigged sloop Heretic. They were recipients of the Cruising Club of America’s 2019 Young Voyager Award.

|

|

The welcome sight of the Aleutian Islands. |