When considering weather conditions for a long ocean voyage, significant emphasis is placed on the high seas portion of the voyage. After all, this is where the majority of the time during the passage will be spent; it is where there is no place to hide from strong winds, high seas and other adverse conditions; and it is where reliable weather information can be more difficult to obtain. Of equal importance, however, are the weather conditions during the first half-day or so of the passage when the vessel is moving from port through near-coastal waters toward the high seas, as well as the final hours of the passage spent approaching near-coastal waters and moving into the destination port.

While on the high seas, the greatest obstacle in utilizing weather information is usually technological in nature. Once a reliable method to obtain weather data and charts has been installed and mastered by the skipper and crew, the voyager will then have the information at hand to be able to know what to expect in the coming days for the passage.

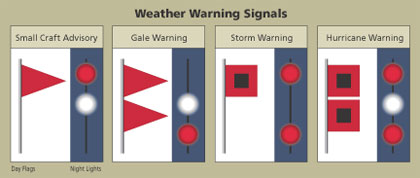

The weather warnings that are provided for high seas areas are consistent in most areas of the world, and this makes categorizing the situations that may arise much easier. Gale, storm, and hurricane force warnings all mean the same thing, whether they are issued for the cold North Atlantic waters north of the Gulf Stream, the Gulf of Alaska, or the warmer waters around Bermuda or the Canary Islands. High seas forecast products are typically issued by a central meteorological service, such as NOAA’s Ocean Prediction Center (www.opc.ncep.noaa.gov) in the Washington, D.C., area.

|

|

USCG photo |

Local forecast offices

When dealing with near-coastal waters, however, the situation is a bit different. First, forecast products are issued by local forecast offices in the area of interest. Second, while gale, storm and hurricane force warnings may still be issued by these local offices and mean the same thing as on the high seas, there are additional warnings and advisories that will be issued by the local offices, and some of these have different meanings depending on the geographic area where they are issued. Advisories and warnings issued by local U.S. offices will be broadcast by NOAA Weather Radio on VHF frequencies, and are typically valid (approximately) for areas that the VHF signal can reach.

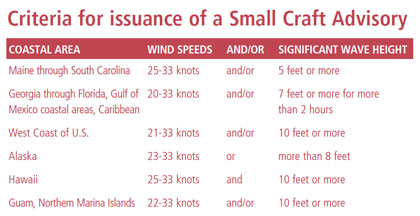

One of the more frequently used advisories in the U.S. is the “Small Craft Advisory.” This advisory has several different definitions depending on the region, and these are shown in Table 1. Sometimes the definition pairs together the wind and sea criteria, but sometimes only one of the criteria is sufficient for the advisory to be issued. A “Small Craft Advisory for Hazardous Seas” can be issued when only the sea state criteria is reached, as in a situation where a long period swell is impacting a region when local winds are light. Also, a “Small Craft Advisory for Winds” can be issued when the wind criteria will be met but the sea criteria will not.

Many ocean voyaging yachts are not necessarily considered small craft, but the issuance of a Small Craft Advisory in nearshore waters can still serve to alert voyagers that conditions may be a bit more challenging in nearshore waters when departing from or arriving to a port. In some areas, when conditions will not quite reach the Small Craft Advisory criteria, the statement “Small Craft Exercise Caution” may be made. This indicates that conditions may still pose a risk to some small craft even though they do not rise to the advisory criteria.

|

|

Weather warning signals in flags and lights show the progression of weather conditions. |

For Canadian coastal waters, instead of a Small Craft Advisory, a “Strong Wind Warning” will be issued when wind speeds of 20 to 33 knots are expected. These warnings, though, are only provided during the recreational boating season of the coastal area of concern. Advisories and warnings in other countries will be different, and will likely be issued and/or broadcast in the local language. If planning a departure from or arrival to a foreign port, determining the local warnings and their criteria well in advance would be prudent.

Another warning that is issued from local U.S. forecast offices is the “Special Marine Warning.” This is typically used over short-duration events such as severe thunderstorms or waterspouts. While these phenomena do occur on the high seas where these warnings are not issued, when they occur in nearshore waters they can affect larger numbers of vessels in higher traffic areas, and due to the proximity of land, the options to avoid them may be more limited.

Surf warnings

A “High Surf Advisory” or “High Surf Warning” will be issued for nearshore U.S. waters when large swells will impact coastal areas, leading to breaking waves. The exact criteria for the advisories and warnings (a warning implies higher seas than an advisory) vary depending on the geographic area. The general idea is to alert mariners to a situation that is much different than normal. Thus, along the West Coast of the U.S. where larger swells routinely impact coastal waters, the threshold for advisories and warnings will be higher than in other areas where large swells are not as common. Large swells in high seas areas, while uncomfortable, are not uncommon and most ocean voyagers are used to dealing with them, but when larger swells move over shallower coastal waters, they will slow down and become shorter and steeper, and thus more dangerous, so yachts that approach coastal waters and become aware that a “High Surf Advisory” or warning has been posted should be prepared for these conditions.

|

|

Local criteria for issuing a small craft advisory. |

Often for near-coastal waters, “Gale Watches” and “Storm Watches” may be issued when there is an increased risk that the respective warning event will occur, but its occurrence, location and/or timing is still uncertain. Watches are not issued for high seas areas, but in nearshore waters a longer lead-time allows more vulnerable smaller craft or coastal locations to make appropriate preparations.

There are other local advisories and warnings that are issued for nearshore waters, most of which are self-explanatory.

The interface between the ocean and the land is often a place where unusual weather phenomena can occur. Of course, the shallower water near the coast will change the sea state, and there can be situations where narrow entrance channels may have their own idiosyncrasies. The difference in atmospheric heating between the land and ocean can create local wind patterns.

Onshore sea breezes in nearshore waters during the afternoon hours can often lead to wind directions that will be very different than the isobars on the surface weather chart might indicate. Thunderstorms are generally stronger over land than over the water but, when they occur near the coast, can lead to strong and gusty winds over adjacent coastal waters, which can in turn produce locally rough seas. In areas where there is significant terrain near the shore, there are certain weather patterns that can generate dangerous localized winds.

|

|

River and harbor entrances, like the Columbia River entrance above, add localized conditions on top of a typical coastal forecast. |

|

Wikipedia |

Local winds

One example is the Golden Gate entrance to San Francisco Bay where the combination of strong heating over the interior and higher pressure over the Eastern Pacific in the summer can produce very strong westerly winds, which will generate higher seas, which can then interact with the San Francisco Bar to create difficult sea conditions.

Studying cruising guides or the Coast Pilots prior to departure or arrival will allow voyagers to become familiar with weather situations that may arise at certain ports. This is particularly important when arriving at an unfamiliar port. Local knowledge at these ports can be invaluable, and while this can be gained from a cruising guide, making contact with another mariner who has knowledge of the port can be even better. This might be a fellow cruiser who has visited the port many times, or someone who has lived in the area for many years.

After a long and successful ocean voyage, it would be a shame if the voyage ended with damage to the yacht or injuries to the crew from dealing with difficult weather or seas entering the destination port. Being prepared with knowledge of local weather patterns, and understanding the advisories and warnings that will be issued for these areas can reduce the chances of a poor start or a poor finish to an ocean voyage.

Contributing editor Ken McKinley is the founder and owner of Locus Weather in Camden, Maine.