A ski area is a trauma factory, and a great place to practice emergency medicine. I was on my second patient of the day and the usual questions were asked: Where did the accident occur, what happened, how long ago, and what seems to be injured? The twist in this case was that the patient was asking me. He had no idea. He was also unsure of the day of the week and the month. He had to think twice about his age and could not quite recall the town he was in. And, most amazing, there was not a scratch on him. He was bright eyed and alert, had good sense of humor and was fun to talk to. And, I’d get to have the conversation with him all over again in a few minutes. Every time I left the room and returned, we were reintroduced for the first time.

This young man was exhibiting anterograde amnesia — the inability to retain new memory. This is an amusing but worrisome sign of traumatic brain injury (TBI), also commonly called a concussion. He had also failed to recall some of his longer-term memory. Both indicate a significant blow to the brain and I was pretty concerned about him. Fortunately, over the next two hours he recovered his ability to remember our previous conversations, and restored the other important facts he’d lost on the mountain. He may eventually even remember the accident itself.

A ship or voyaging sailboat is not quite as exciting a place to practice medicine, mostly because the local population of trauma candidates is much smaller. But with swinging booms and davits, loaded lines and violent sea motion, the potential for injury is still significant. The head is particularly vulnerable since it sticks up above everything else, is often inserted into places it does not belong and generally arrives first at the scene of an accident.

Severity can differ

Any change in brain function at the time of impact gives us the diagnosis of TBI. Traumatic brain injury can range from the very mild to the very fatal, but it is the problems in between that cause the most angst. Being able to distinguish the less serious TBIs from the more serious ones should become part of your basic offshore emergency medical skill set.

The impacts that kill outright or within a few minutes are chillingly straightforward. The lethal event is usually rapid hemorrhage into the cranium resulting in brain failure. There is no field treatment. CPR will not help and neither will your defibrillator.

|

Less significant impacts can result in slow bleeding inside the cranium or swelling of the brain tissue itself. The patient survives the initial insult, but can develop problems several hours or days later as pressure rises inside the skull (intracranial pressure, or ICP) to the point that blood flow to the brain is impaired. With this anticipated problem in mind, it would be wise to evacuate a TBI patient early rather than wait for the condition to become worse. This decision is relatively easy when you are inshore and close to a hospital.

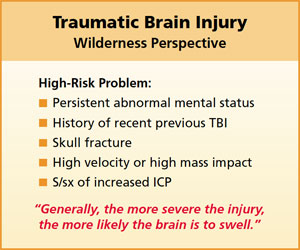

The decision is more difficult when you are offshore or in another remote setting where evacuation will be difficult or dangerous. This is the classic backcountry medical dilemma. Is the benefit of access to more advanced medical care worth the risk to the ship, the crew, the rescuers and the patient? When, exactly, is a TBI a high-risk problem?

The brain is not like a broken leg or dislocated shoulder where we can see the deformity and test the circulation to assess the severity of injury and the efficacy of our treatment. Instead, we have to assess brain function as an indirect measure of integrity. There are no absolute rules to fit every situation, but there are some general guidelines to help with your risk/benefit assessment.

Generally, more significant changes in brain function indicate more significant trauma. There is a higher probability of increasing ICP when brain function does not return to normal shortly after the event. A history of previous TBI is also of concern, especially if recent. Incompletely healed brain tissue is more prone to swelling, and scar tissue is more likely to bleed. An elderly patient, or one taking blood thinners, is at increased risk as well.

An injury that causes a brief loss of memory for the accident itself but leaves everything else intact is not particularly worrisome. In an otherwise healthy person, this is very unlikely to result in dangerous bleeding or brain swelling and is not worth a high-risk evacuation. A more significant loss of memory, like that exhibited by my ski area patient, indicates a more significant brain injury that is more likely to result in increased ICP. In his case, though, the rapid improvement in symptoms and return of short-term memory was reassuring.

If this ski area patient had instead been involved in an accident aboard my boat in Penobscot Bay, I would have taken him ashore even though he was improving. The risk of evacuation would have been low and the benefit of having him close to medical care would have been worth it. If we had been halfway to Bermuda, the risk versus the benefit would have been quite the opposite. The diagnosis in either location is the same: High-risk TBI with improving mental status.

|

|

Suction device improvised from a 60cc catheter tip syringe and a nasopharyngeal airway. Total cost approximately $4. |

|

Jeff Isaac |

Curiously, the improvement or decay in mental status is a more reliable indicator of severity than the duration of unconsciousness. A person who was knocked out for 10 minutes but returns to normal quickly after waking may not signify much of an emergency. Early return to normal mental status, even after a scary event, is a good sign. It is the crewmember that is not returning to normal that is considered high risk, even if there was only a brief loss of consciousness or memory. Depending on sea conditions, if the diagnosis is high-risk TBI with persistent altered mental status, it may be worth the risk of transfer to a larger ship or a helicopter before increased ICP develops.

Although we tend to focus on the patient’s behavior and memory, it is important to anticipate the more direct threats to life that will develop if the brain begins to swell. This is especially important where evacuation will be delayed or impossible and you will be caring for the injured crewmember for a long time. While you cannot do anything about the development or progression of increasing ICP, you can do a lot to improve your patient’s chance of surviving it.

Increased ICP is most likely to develop during the first 24 hours and the patient should be carefully monitored during this time. The early symptoms of elevated ICP are unmistakable: severe headache, persistent vomiting and altered mental status. Choking on vomit in the upper airway or aspirating vomit into the lungs can be fatal. Positioning the injured crewmember in a berth in the recovery position will help prevent this. Keeping the patient close-by will allow you to intervene with suction or gravity drainage when necessary. On a short-handed boat, the patient may be safer on the cockpit sole near you, rather than out of sight in the V-berth.

Allowing the TBI patient to sleep is fine, but not alone. He or she will not sleep through the pain and vomiting of increased ICP. Be sure to pad and insulate them well. Since the patient will not be moving around much, he or she will be set up for hypothermia in all but the warmest environments.

In a prolonged event, dehydration will become an issue. It would be helpful to provide fluid resuscitation by IV or subcutaneous infusion. The latter technique is called hypodermoclysis and is easy to learn, safe to perform and the supplies are inexpensive. It can be a lifesaver in any case of slow onset dehydration. Medication to control vomiting may also be useful but generally doesn’t work very well in serious brain injury.

Post-concussive syndrome

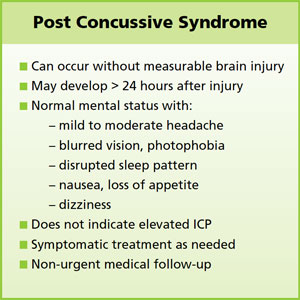

Any TBI, even the very mild ones, will result in some degree of post-concussive syndrome. Symptoms include mild nausea, loss of appetite, photophobia (lights bothering your eyes), mild headache, fatigue, irritability and emotional lability. The latter is pretty interesting. I saw two patients this season where the presenting complaint was continued crying. Both were post-concussive from minor injury. It was reassuring to note that both had normal mental status; knowing the who, where, why and when of their situation. Long and short-term memory was intact. There was no vomiting or severe headache. But, there was clearly something not quite normal about brain function. The symptoms had persisted for over a week since the original injury, but resolved over the following 10 days or so.

|

Post-concussive syndrome can wax and wane and persist for days or weeks. It can be annoying, but does not indicate a serious condition as long as mental status remains normal and none of the other signs of increased ICP develop. The ideal initial treatment is to put the brain to rest, avoiding excessive stimulation like tide and current calculations, viewing radar, and trying to decipher confusing navigation lights. This would not be a good time to begin a passage.

If you are already at sea and cannot avoid brain-intensive tasks, recognize that you are not functioning at 100 percent and allow extra time and take extra precautions in everything that you do. Spend as much time as you can at rest with your eyes closed. Even reading and intense conversation can delay recovery.

Scalp laceration

While my ski accident patient was recovering, I examined his helmet. It didn’t prevent his TBI, but it probably saved him from a scalp laceration, skull fracture or at least a big goose egg. Since helmets have become popular with skiers, we have seen very few scalp lacerations or skull fractures. Sailors could learn something from this.

Scalp lacerations from blunt impact are often full thickness and really messy. The scalp is part of your brain’s protection detail, absorbing the energy of impact by deflecting and then tearing. Bleeding can be profuse with small arteries spurting all over the place. Don’t be dismayed by this; these wounds look more significant than they are. Nevertheless, quick first aid is a good idea. It is possible to lose a significant amount of blood from a large scalp laceration.

Have the patient hold pressure on the wound with a big gauze pad or towel continuously for 20 minutes. If he is on a blood thinner or some kind, allow twice that long. With continuous firm pressure, the bleeding will stop. It is probably a good idea to keep the patient on deck until this is accomplished. Chumming for sharks is better than a blood-slicked cabin sole any day.

If the patient is awake and cooperative, consider sending him to the shower if you have one. Running clean water over the scalp is a perfectly acceptable way to clean the wound and the rest of the patient. There will be more bleeding during the process, but generally a lot less than right after the injury. After cleaning, apply more pressure until it stops.

You can now inspect the wound and clean up the mess. You might be able to see the surface of the skull when you inspect the damage. Take your time; it is actually really interesting. Look for signs of skull fracture. Bits of bone will increase your long-term concern but not really change your field treatment.

Patching a torn-up scalp is fairly straightforward. Allow the piece to flop back into position, and cover it with a large gauze pad and a watch cap. The scalp will heal quite well this way. Change the gauze as needed until the wounds dry over and start to knit back together. Then a protective cap is all that is necessary. If the patient is balding, remind him that the developing scar will be particularly sensitive to sun damage.

|

|

A combat pressure dressing, like this Israeli bandage, can be used to control bleeding of the scalp during initial treatment. |

|

Jeff Isaac |

If you have the training and equipment to staple or suture the wound, so much the better. You can also tie clumps of hair together across the wound to bring the wound edges closer. Healing will be a bit faster that way. If you suture, consider that several large-bite, full-thickness interrupted sutures may be easier to place and work better than a lot of small ones. If you staple, you don’t have to apply one every few millimeters. A few widely spaced staples to tack the flaps in place are sufficient. The scalp has remarkable healing properties, as anyone working the Emergency Department in a town full of drunken sailors can tell you.

Finally, there are two really important things to remember when dealing with scalp lacerations. First, don’t let all the blood and mess lead you to declare an emergency when there isn’t one. Second, don’t let all the blood and mess distract you from finding an emergency when there is one.

Prevention

Body armor and helmets on sailboats — has really come to that? As yacht racing officially joins the ranks of contact and impact sports, some cruising sailors are left shaking their scarred and bruised heads wondering if they should be wearing helmets, too. I, for one, will never do it. But I said that years ago about hockey, skiing, biking, and bull riding. Now I feel naked without one.

There are some good lightweight and close-fitting brain buckets that could make sense for deck work in heavy weather. A helmet may not prevent the TBI from a hard impact, but it would avoid giving your mate the opportunity to test the skin stapler. Just Google “sailing helmet” for lots of examples.

Jeff Isaac, PA-C, is the curriculum director for Wilderness Medical Associates International and the principal instructor for Offshore Emergency Medicine. He is a licensed captain and an experienced blue water sailor.