Key facts voyagers need to know about these valuable units

With a few exceptions, most electric marine water heaters are simply scaled-down versions of those used in homes and businesses the world over.

The components of these units are relatively simple. An electric heating element is immersed in the water contained within the heater’s tank. It, in turn, is controlled by a thermostat which regulates the temperature of the water. When electricity is applied, the heating element warms the water within until the set point on the thermostat is reached, at which point the heating element turns off.

Water heaters also typically include an important safety device, a pressure/temperature relief valve. This is designed to relieve pressure within the water heater’s tank in the event of a malfunction. If, for instance, the thermostat that controls the electric heating element malfunctions, and the water within the heater rises to the boiling point, creating steam and extreme pressure, the pressure relief valve will open and vent the pressure before the condition goes super critical. Of course, if the pressure relief valve is damaged, malfunctioning or capped, then it won’t be able to provide this all-too-necessary safety feature.

Even when a pressure relief valve is working properly it can pose a hazard. Several years ago, while I was managing a boat yard that was responsible for commissioning new vessels, a mechanic was injured by a water heater as he worked alongside it when the pressure relief valve unexpectedly vented, flooding the area with boiling water and steam. Fortunately, his injuries were not severe, however, a subsequent investigation revealed that the thermostat had been improperly wired, essentially bypassing its important control function, rendering the heating element continuously energized. For this reason, the discharge of a water heater’s pressure relief valve should be securely plumbed into the bilge or away from areas that may be occupied at any time. Flimsy hose or tubing simply slipped over the valve’s outlet pipe is inadequate, as it will be blown off by high pressure water and steam. It must be robust and securely clamped in place.

If the vessel is equipped with a direct dockside water pressure system, one which enables a continuous supply of dockside water, the water heater’s pressure/temperature relief valve must be plumbed so that it vents directly overboard. If it’s not installed in this manner, and the valve leaks, the vessel could flood with an unlimited supply of dockside water. Plumbing a pressure/temperature relief valve directly overboard does have one drawback: If the valve leaks, it’s possible it will go unnoticed.

Heat exchangers

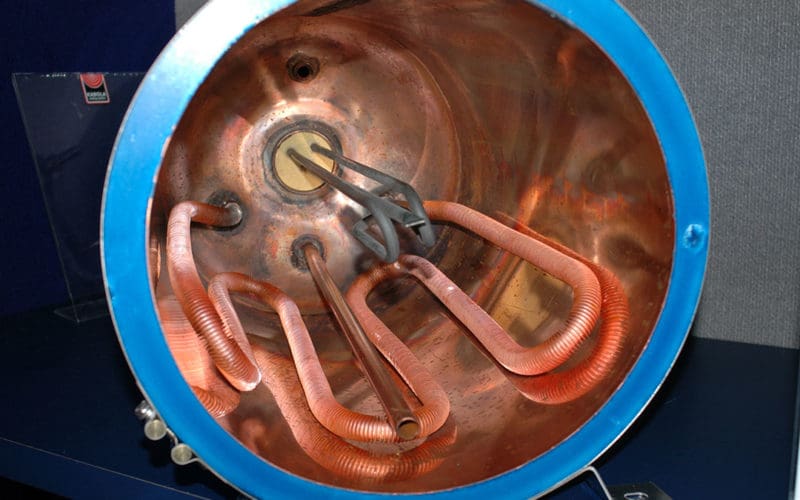

One feature that marine water heaters, for those so equipped, do not share with those ashore is the heat exchanger. The heat exchanger, much like the one on your engine or generator, simply transfers heat generated elsewhere, in the engine’s closed cooling system or from a diesel-fired hydronic heating system, to the water inside the water heater’s tank. This arrangement is extremely common and has been used effectively for decades. Instead of sending all of the excess heat created by the engine out with the exhaust, some of it is reclaimed for washing dishes, taking showers, etc.

As well as the heat exchanger scenario works, there are a few caveats associated with its use. Utilizing engine coolant to make hot water means the water heater must become part of the engine’s closed or coolant-filled cooling system. While most engine manufacturers make provisions for a water heater connection, when pressed they aren’t keen on the idea because it takes complete control, design and implementation of the cooling system out of their hands; in some cases, they may require another heat exchanger and circulation pump close to the engine.

If the engine’s cooling system fails because of a design or manufacturing flaw, the engine manufacturer is usually responsible for repairs, provided the engine is under warranty. If, however, the plumbing between the engine and the water heater fails, the engine will almost certainly overheat, potentially causing permanent damage, while leaving the vessel powerless.

The engine manufacturer, however, bears no responsibility for a failure of this sort. Therefore, make certain the hose used to connect the engine’s cooling system to the water heater is especially rugged, chafe resistant and robust; hose that carries a J2006R “Marine Wet Exhaust” rating is ideally suited for this role, while ordinary “heater hose,” in spite of its name, may not be up to the task because of its propensity to crush, kink and chafe when routed off the engine and through the vessel.

Additionally, when a water heater is connected to an engine’s closed cooling system certain protocols, as well as the engine manufacturer’s instructions for such an arrangement, must be followed closely. Primary among these is the location or elevation of the water heater, or more specifically its heat exchanger. If the heat exchanger within the water heater, or any portion of the plumbing between the engine and the water heater, is located above the engine’s expansion tank cap, then a remote expansion tank must be plumbed into the system. This tank, with its own pressure cap, then becomes the primary fill point for the closed cooling system, rendering the original legacy fill cap dormant and unusable. In most cases, when a remote expansion tank is installed, it must use a pressure cap that the engine manufacturer calls for while the original cap located on the engine must be replaced with a higher-pressure rating cap. The reason for this cap swap is to ensure that only the highest cap in the system, the one that can vent air, opens and closes with temperature-induced pressure changes, while the cap on the engine’s expansion tank remains sealed at all times.

Hot water temperature

Another peculiarity of the marine water heater when it’s interconnected with the engine’s closed cooling system is the temperature of the water it’s capable of producing. The traditional, built-in thermostat controls only the electric heating element, which is typically set somewhere between 120degrees and 140 degrees Fahrenheit. It’s important to note that water heaters are normally set to temperatures above 131 degrees to prevent development of harmful bacteria, such as Legionella, the cause of Legionnaire’s disease, in the water supply. This is of particular concern with marine water heaters because they are turned on and off, which means they often contain stagnant, tepid water, which is an incubator for water-born bacteria.

Water at a temperature above 106 degrees is considered painful to some. Personally, I consider 109 degrees the perfect shower temperature, while my wife believes this is much too hot. She prefers something around 105 degrees, (our teenage children didn’t seem to care what the temperature of the water is as long as they used all of it). Anything under about 95 degrees begins to feel chilly. As you can see, there’s not much of a range between comfort and pain or potential injury. At a temperature of 131 degrees Fahrenheit (55 degrees Celsius), a child can be scalded in less than four seconds.

Therefore, it often comes as a surprise to boat owners that the coolant issuing from the engine, and going to the water heater may be as hot as 195 degrees, perhaps 180 degrees by the time it reaches the water heater. Without any external control, water exiting the water heater may be nearly this hot, which clearly presents a serious burn risk. Not long ago, while inspecting a vessel, I opened a galley faucet while underway, only to have a cloud of steam billow forth. It was a sobering experience.

There are two ways this potential safety hazard may be dealt with, both of which offer the same point-of-source approach. The first involves using a mixing or tempering valve. This adjustable device, installed at the water heater, controls the temperature of the water leaving the water heater by mixing it with cold water in order to lower its temperature to the desired level. Therefore, regardless of the temperature of the water in the water heater or the coolant running through the heat exchanger, the output temperature remains constant. The mixing valve has an added benefit, because it enables the water in the water heater to be maintained at a much higher temperature, it effectively provides the user with more hot water for one simple reason: not much of it is needed as it’s mixed with cold water to produce the desired 100 to 110 degrees temperature range.

Adding a mixing valve

Mixing valves can be added to virtually any water heater as an aftermarket item, after which the water heater’s thermostat can be increased to maintain a higher electrically-heated pre-product water temperature. It’s important to note that not all mixing valves’ reaction times are quick enough to consider them as anti-scald protection. A variety of standards exist concerning the design and performance of these valves. For more info on this subject it’s worth a visit to www.watts.com/pdf/pg-mxv.pdf. If instantaneous anti-scald protection is desired, then install anti-scald faucets.

The other method utilizes a component known as a temperature compensation valve or TCV, which is plumbed, externally, to the water heater’s coolant heat exchanger while sensing output water temperature. This product takes a slightly different approach in that it controls the amount of coolant running through the water heater in such a way that it maintains a water output temperature of about 140 degrees, which does present a scalding risk.

The beauty of either of these approaches is that they limit the temperature of the water leaving a water heater, regardless of whether the heating source is the electric element or the engine’s coolant. Quick reacting anti-scald valves are, of course, desirable, particularly for showers and sinks; however, it may not be practical or economical to equip every fixture aboard with one of these, particularly after a vessel is built. That’s where mixing valves and TCVs come in. If your water heater is connected to your engine’s cooling system you’re playing with fire unless you install one of these inexpensive devices.

Finally, many water heaters are installed using a check valve on the cold-water supply, which serves two purposes. One, it prevents water from running out of the water heater, potentially damaging the element. Unless it includes protection that prevents it from operating while dry, water heater elements must be submerged while operating. If exposed, their lifespan can be measured in seconds. Two, the check valve minimizes convective heat loss, and comingling of hot and cold water, which also hastens heat loss. If a check valve is installed, the water heater must also be equipped with an expansion tank, which allows water in the water heater to safely expand as it’s being heated. Without this component, the water heaters pressure/temperature relief valve is likely to (hopefully) open, thereby wasting hot water, and defeating the purpose of the check valve. ν

Steve D’Antonio is an ABYC-certified Master Technician and sits on that organization’s Engine and Powertrain, Electrical, and Hull Piping Project Technical Committees. He owns Steve D’Antonio Marine Consulting (stevedmarineconsulting.com) which offers marine systems consulting and pre-purchase services to boat owners, boat builders and others within the marine industry.