The waters around Cape Hatteras are the subject of much research with the most interesting —from a cruiser’s point of view — being a study of currents. Recent research from a collaboration between the U.S. National Science Foundation and researchers from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, provides some of the best insights available for this complicated area.

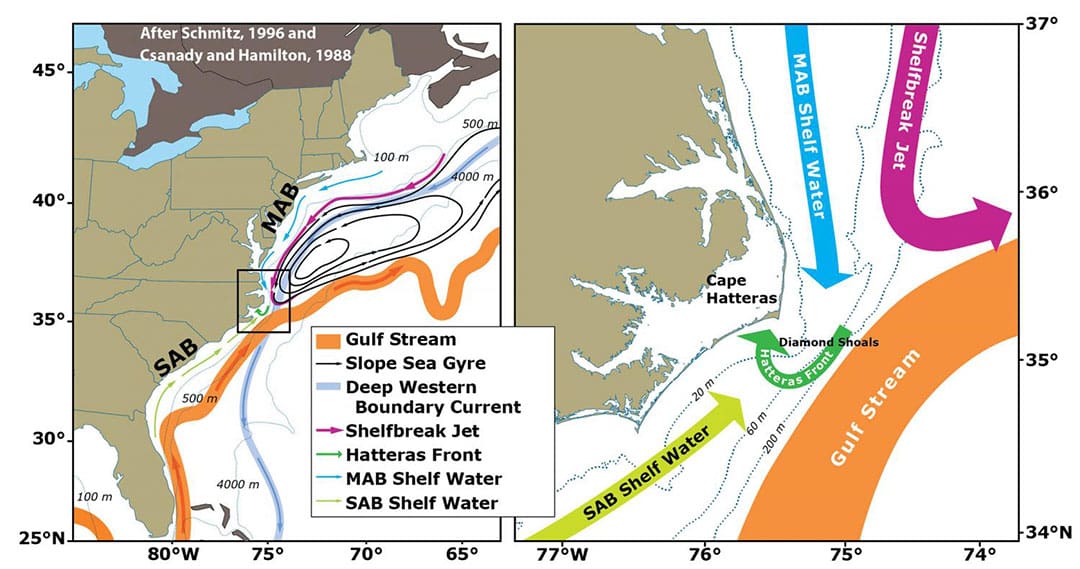

A study called Processes driving Exchange At Cape Hatteras Program (PEACH) just completed, with additional research to follow. Figure 1 is a PEACH graphic showing the complicated systems of currents impacting boats transitioning through the area. The purple arrow denotes the Shelfbreak Jet, running north to south along the continental shelf edge. The blue arrow denotes the Middle Atlantic Shelf, also running north to south. These two colder currents meet the northeast-flowing Gulf Stream off the tip of Hatteras. The currents coming from the south include both the much warmer Gulf Stream as well as the warmer and saltier Southern Atlantic Bight (SAB) Shelf waters. The SAB is the light green arrow coming from the southwest. There is a smaller bright green semicircle marking the Hatteras Shelf, which includes a sudden and rapid drop from shelf to deep sea floor. Along these shelf areas and to the immediate east, where the currents collide, cruisers have experienced what they call the washing machine. The sea states are dramatically impacted during storms as well as northerly wind against current events. Figure 1 clearly shows an area where boats can find more extreme cruising conditions due to sea-against-wind conditions.

The Gulf Stream, part of the Atlantic Ocean circulation system, forms one of the largest and most critical cape current features. It follows a path along the east coast of the U.S. to Hatteras. It is at this convergence point the current then sheers off to the east and into the North Atlantic and changes from a “boundary-trapped current to a free jet” and where “the magnitude of this convergence implies a large export of shelf water to the open ocean.” (Oceanography, The Official Magazine of the Oceanography Society, tos.org/oceanography/article/overview-of-the-processes-driving-exchange-at-cape-hatteras-program).

Difficult seas

For boaters, this means a sudden and fast flow of water which can cause rapid sea stage build and those dreaded flat backed breaking wave sets. This is especially true of the areas just to the east of the Hatteras land form, just off the shelf where currents collide. The danger area of three currents merging is clearly seen in Figure 1 plus, it’s the area where the Gulf Stream changes to a free jet headed east.

It’s best not to make a passage here in wind against current situations, as a 25-foot wave can actually have a close to 50-foot drop. Even a slight northerly or northeastern component can cause rapid, large and short-period waves to suddenly form. And from experience, a hull hitting water from height coming off a wave is like hitting a concrete wall. Plus in this kind of sea state, even attempting to take a wave at a favorable angle does not eliminate the breaking wave danger. Winds against current are always issues in oceans. On the converse, winds with currents, as mentioned in the “Gulf Stream Waves” article, can lead to flat, smooth seas; our most memorable crossing featured a heavy fog bank as we approached the edge of the stream, then suddenly breaking through to heat and absolutely turquoise waters with sargassum weed strands. It is these features that have raised the interests of researchers as obvious changes have been seen since at least the 1960s.

While PEACH research has concluded, additional work is ongoing to identify the changes we are experiencing with the Gulf Stream, along with weather implications. “An important change in recent years is in an increase in the meanderings or ‘wiggliness’ of the Gulf Stream. In addition the Gulf Stream has been generating more ‘Warm Core Rings’, large clockwise eddies.” (National Science Foundation, Ocean Observatories Initiative, Fishermen and OOI Scientists Working Together to Advance Science).

Other floating things

Another issue for captains to consider as they plan routes are the buoys, boats and other objects found off the cape. Besides currents, there are the research or energy generation objects located in the waters off Cape Hatteras and the Norfolk Canyon. Many may not be listed on current charts or updates to those charts.

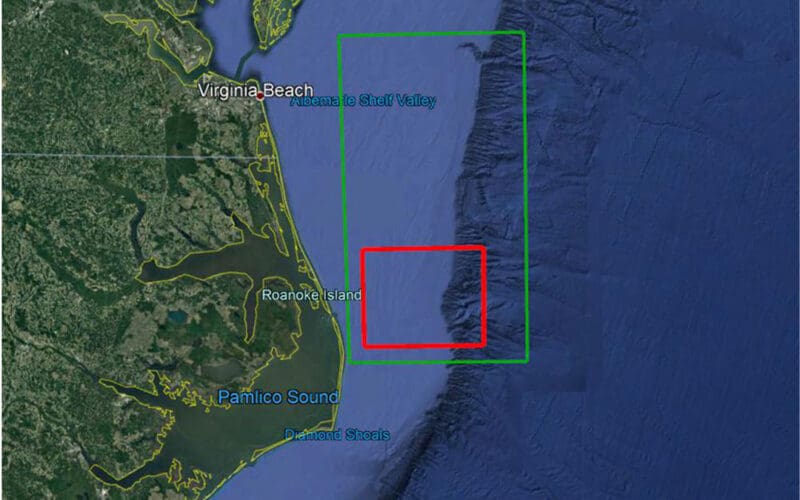

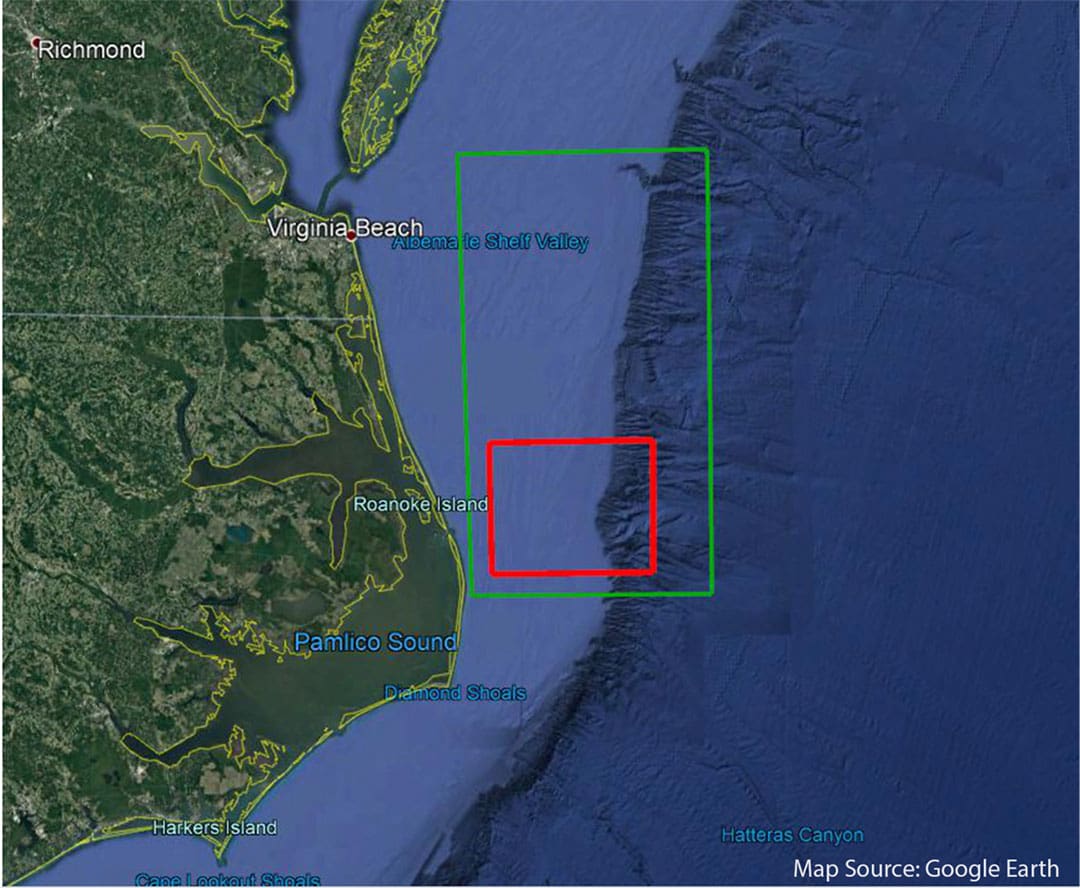

Post PEACH, the next research efforts include the relocation of the Middle Atlantic Bight (MAB) Pioneer Array of scientific buoys to the offshore Hatteras area. This moored array includes 11 moored buoys and two gliders. The location is the region of the MAB between Cape Hatteras and Norfolk Canyon. Per publications, the “region offers opportunities to collect data on a wide variety of cross-disciplinary science topics including cross-shelf exchange, land-sea interactions associated with large estuarine systems, a highly productive ecosystem with major fisheries, and carbon cycle processes. This location also offers opportunities to improve our understanding of hurricane development, tracking and prediction, and offshore wind partnerships.” (NSF, Ocean Observatories, Initiative).

Figure 2 shows the Pioneer Array, MAB Regions for the deployment of buoys in the red square. The green square is the operational area for operations of underwater autonomous vehicles. The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill participates in this research. The moorings are said to be in place, with dates between 2023/24 for full operation. The buoys should be clearly seen on ships’ radar, and may transmit Automatic Information System (AIS) signals; charts should be updated to avoid these objects.

More obstacles to chart include the new energy generating turbines, or wind farms. Of most interest for passaging vessels are the new pilot wind farms being installed at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. While not a direct issue for Cape Hatteras, they are located in the operational area of the MAB Pioneer efforts. And they are something for cruisers to be aware of for route planning. “The 112,799-acre lease area will see an additional 188 turbines, with construction set to begin in 2024 and an estimated completion date of 2026 in this area.” (USA NOAA Office of Coastal Survey, nauticalcharts.noaa.gov/updates/surveying-the-approaches-to-the-chesapeake-bay/). Additional projects include similar turbines off Ocean City, Maryland. Updated charts will be critical for safety in these areas of development and research. n

Joan Conover is president of the Seven Seas Cruising Association and an experienced offshore cruiser.