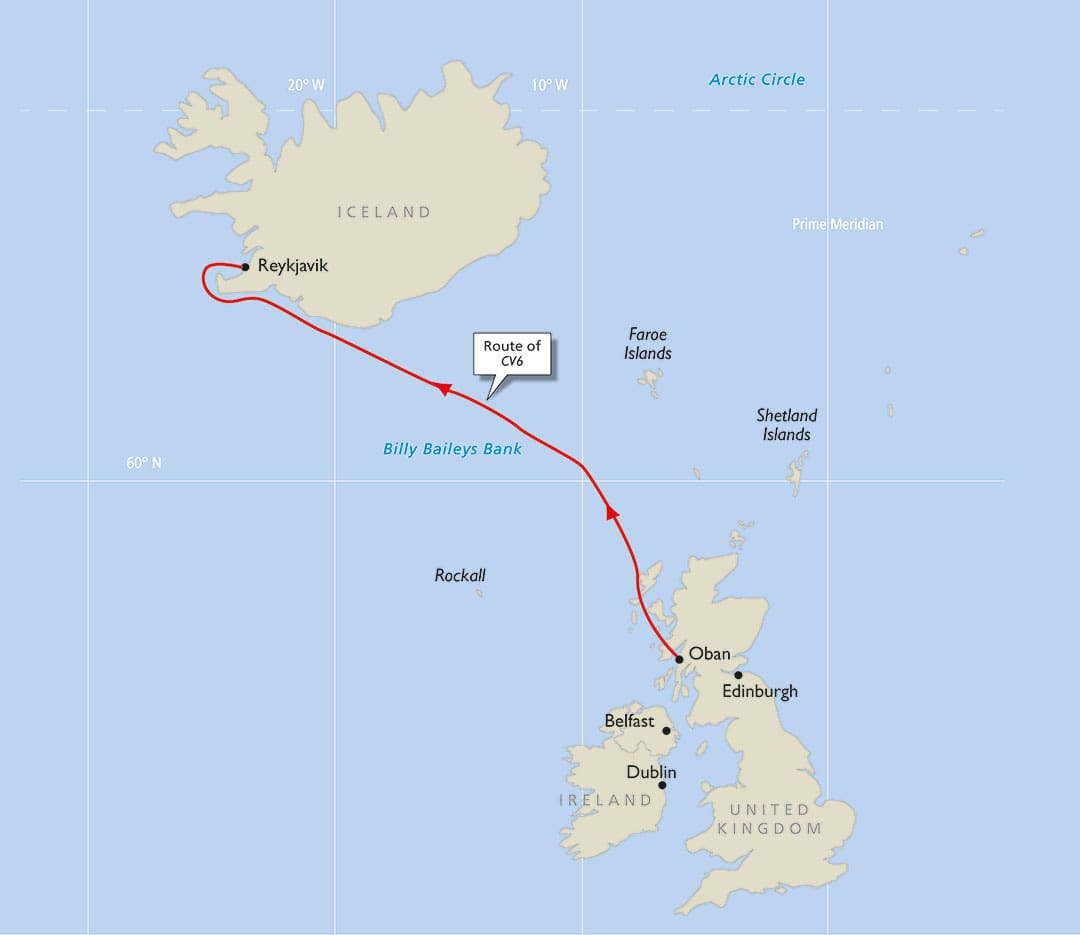

We had tacked past the mighty seamark that is Barra Head and out past St Kilda, carrying a reduced sail plan into the wide Atlantic on our passage from Oban in Scotland to Reykjavik in Iceland aboard the Clipper 68 CV6, operated by Skirr Adventures, based in the UK. We were accompanied by a second Skirr Adventures boat CV11.

The rising sun was scraping filigree from the wavetops and burnishing the clouds’ undersides. The watch was alert on these night-blue ocean swells. Then — a blowspout. Only one, and it was huge. Then all suggestions of its existence disappeared. ‘Did you see it?’ The watch on deck — consisting of three somnolent sailors —was only half convinced. A glittering shower of gold against the clouds. Could it have been a blue whale? We were in the locale for viewing these whaling nations, for taking a ride through their terrain, and for following them as they hunted in their own fields.

The journey surprised me by the number of marine mammal sightings. As is often the case when moving from a busy land-based life, when I go out from the coast and settle into the watchkeeping system on the ocean, a sense of mal de mer and sleepiness overtakes me. There is nothing like ‘Thar she blows!’ to shake you out of it. CV6 had cruised under a single-reefed main, staysail and yankee three through the comparatively sheltered glacial furrow that is the Sound of Mull. The skipper, Bob Beggs (one of the most experienced offshore professionals anywhere in the world) would use the same conservative sail plan as we tacked past Barra Head and out past the grey-green tooth that is St Kilda, and into the wide Atlantic.

Tracking sharks

Off watch and below I caught sight of the YellowBrick tracking view cached on a mobile phone screen. Unlike Navionics or paper charts where the water is a blank white canvas speckled with depth markings, this YB setup just showed the vessel alone in a deep cyan sea. Scotland was a uniform dark green. I was instantly reminded of the trackers attached to some large great white sharks off the United States’ eastern seaboard. The Atlantic White Shark Conservancy just shows the fish, its recent track, land, sea, and nothing else. But those celebrity sharks such as the one the Conservancy labelled ‘Mabel’ were unlikely to be accompanying us on this trip. At a cruising speed of eight knots, CV6 began her long beat towards Iceland. Day after day on the port tack, gazing to windward, I was thinking of one of the Anglo-Saxon phrases connoting “sea” — “hronrade” — meaning the “whale’s way,” or the “whale’s road.”

The high seas are home to overlapping territories of whale and dolphin. Pilot whales have been seen in large schools of up to a hundred individuals. The ones we saw were in far smaller groups. Three of them, a mother and calf, and another family member wallowing alongside. Their rounded foreheads shunted a film of water upward, like the bulb on the stem of a fast-moving cargo carrier. Dolphins racing alongside communicate a clearer sense of delight, with their clicks, whistles and squeals. Pilots make similar sounds but because they keep further off, are heard far less. Pilot whales’ chattiness is sadly most evident in their distress calls. They were, according to one guide, hunted till recently in Orkney and Shetland, and they still are in the Faroes. Greenlanders still take several hundred a year.

The Faroe Islanders’ hunt is called grindadrap and is, for those who have seen it up close, a stomach-churning spectacle. Dozens of whales are driven towards a beach. Fishing boats form a barricade behind to prevent their escape. The slaughter turns the bay crimson. A recent documentary argues the hunt ought to be discontinued because it is endangering the health of Faroese consumers. The pilot whale is a predator of squid and thus near the top of the food chain. Heavy metals and organic toxins have accumulated in its flesh and could poison those who eat its meat.

Commercial shipping appears to be a threat to pilot whales. They were reluctant to come closer than 20 metres to our yacht and they did not appear to be moving very fast — as compared to the dolphins that would jink out of the path of one’s prow at the last moment.

The calf we saw on passage from Scotland to Iceland — in the vicinity of Bill Bailey’s Seamount, north of Rockall — was probably quite young and would be suckling its mother for another year. Most pilot whales are born in the month of August. There is a gap of at least two years between offspring and the total number of calves per mother is not high. Once in the world, however, a pilot whale may live up to 50 years.

Signs of the blue whale?

A large blowspout was definitively witnessed, one sunny dawn north of Rockall. The height and breadth of the spout is indicative of a whalebone whale or rorqual. Could it have been a blue? Once between the easternmost and middle islands of the Azores, on a stormy day, I did see a gigantic blowspout in the offing, and then nothing amid the white slather of breakers. No tail to show, nor the giveaway thick shank leading up to the flukes. One would like to think it was the largest animal ever to have existed. Who is to say otherwise? Iceland and the Azores are both within the range of the blue whale. It likes to stay offshore — but then there are only several thousand left in the whole planet.

Scientists estimate there are up to 3,000 individuals in the North Atlantic. Should this errant spout south of Iceland have belonged to a blue, it could conceivably have been the same individual sighted in the Azores. The two island groups are on the same longitudinal strip highlighted as part of the local range. Blue whales were hunted until the 1860s off Norway — their huge size offering the harvesters the biggest yield for a single animal; the species has been listed as endangered since 2018.

Nearing Iceland the bottom got appreciably closer. The depth sounder — flashing for days on 13 (or sometimes even more alarmingly, at two) meters — suddenly became a solid response as we came into more like 100 meters of water. Iceland is in some ways a splodge of cooled lava sitting on the Mid Atlantic Ridge. The shallows around it are more regular contours, resembling more closely the edges of a spreading pancake.

Fulmars had been surging, swooping, flapping and gliding all around the boat for days.

“We’re seeing plenty more birds,” affirmed the Australian helmsman as he handed over from the night watch. He was beaming, as he went below, relieved at the coming landfall. The wind had come right off from the Beaufort Force 5s and 6s of the passage, leaving us to motor into a peaceful sunrise. We were to round the corner of the Reykjanes Peninsula and enter Faxafloi, the broad bay home to Iceland’s capital.

A last sighting

Another blowspout. This time on almost oily, gradual swells. Not a blue, for sure, but still a big whalebone beast. I caught sight of a low line like a diving submarine. It could have been a snout, or a back. It was smooth, not hummocky like the spine of a Sperm Whale. No tail. There was a distinctive jet-black line with a bright white counterpart underneath. Very probably a Humpback. I imagined them lazily circling around fish as so gloriously shown on the television nature documentaries, enclosing the bait ball in a curtain of bubbles, before opening their jaws side on like a massive spoon. Seabirds were bombing a tight disc of the ocean surface. The water was being agitated — possibly by fish tails — as the aerial hunters fought among themselves for the scraps. Several fins loped by on either side of the boat.

‘There!’

‘Here, whale!’

We chased the pointing arms on either side, necks switching like spectators at a tennis match. Each time the fin disappeared before anything could be confirmed. Then at 100 meters on the port quarter, the tell-tale breaching of a common dolphin. Exuberant bellyflops and then nothing. Gone.

We were pleased after a hard upwind sail on the edges of the Icelandic Low pressure system to see the lighthouses on this southwestern corner of the island, the smooth green fells falling vertiginously to the water’s edge, the mighty seamark that is the Hallgrimskirkja (the concrete-coloured modern cathedral which dominates Reykjavik) and the clean, cold lines of the local fishing fleet. All those navigational calculations which enabled our landfall had been achieved quickly and effortlessly by the whales which made the same trip. To a mind more scientifically inclined, these wonders may be slightly less astounding. The marine biologist’s understanding will provoke much deeper questions.

In a fanciful way the sea — especially these Icelandic waters — is full of these whaling nations. Perhaps another and better use for that dull phrase for the diplomatic group of countries — Iceland, Japan, Norway — which has been cast down in the eyes of Western governments and conservationists since the Greenpeace Save the Whales campaign took off in the Eighties. An imaginative way to consider these marine mammal species, adapting to a planet heated by humankind’s fossil fuel emissions. n

Ben Lowings is a maritime writer, an editor at BBC World Service radio news and a yacht delivery skipper around Britain and northwestern Europe.