Liesbet Collaert and Mark Kilty met in the San Francisco Bay Area in December 2004. She was exploring the U.S. while on a sabbatical from Belgium and he dreamed about sailing the world on his own boat. She was prone to seasickness and had never set foot on a sailboat before, while he had two furry children and was sick of the rat race. Love prevailed and new adventures awaited. Liesbet never returned to Belgium.

The couple bought an Islander Freeport 36 and, together with Mark’s two rescue dogs Kali and Darwin, they set off across the horizon. They didn’t get very far. The dogs hated the Pacific Ocean. The constantly heeled monohull and the rough seas made everybody miserable. The horizon ended in Monterey two days later, where the family sold their sailboat within weeks. They traveled to Mexico and beyond in a truck camper instead. After a year of level ground and no vomiting in Latin America, they returned to the U.S., planning a move to Belize. That’s when Mark suggested to go cruising again, on a catamaran this time.

Liesbet, Mark, Kali and Darwin found their new floating home in Annapolis, Md., in the spring of 2007. It was a 35-foot Fountaine Pajot Tobago they called Irie, which means “all is good” in Jamaican English. Two hulls made all the difference! They happily motored down the Intracoastal Waterway, where Liesbet learned all about navigation and the dogs rested comfortably in the cockpit. The Bahamas, with its sublime beaches and crystal-clear water, were a highlight for both the dogs and humans. Hurricane season was spent in the Dominican Republic after a month-long visit to the Turks and Caicos Islands. Along the south coast of Puerto Rico, Kali sadly passed away. Reduced to three, the family reached the Eastern Caribbean, where they sailed up and down the island chain for three years after starting a long-range Wi-Fi business, The Wirie, from their boat in St. Martin. From then on, Internet was needed in every anchorage so they could make money with their business and keep on cruising. Liesbet added to the cruising kitty by becoming a freelance writer.

|

|

In the San Blas Islands, Panama. |

|

Liesbet Collaert |

After Darwin passed away at the end of 2010, the couple made one last trip up to St. Martin for the cruising season before heading to the Western Caribbean, where they enjoyed a year in the magnificent San Blas Islands. In January 2013, it was time to transit the Panama Canal and enter the Pacific Ocean once more. Irie was small to be dealing with heavy seas, but she made it safe and sound, first to the intriguing Galapagos Islands, where two months of living among exciting creatures proved unforgettable, and then to French Polynesia, where the Gambier Islands offered unique shores and coral-rich waters.

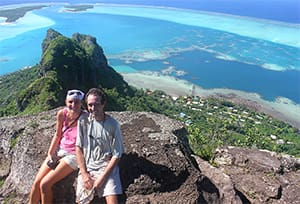

Mark and Liesbet sailed throughout French Polynesia for two years. They reveled in the spectacular scenery of the Marquesas, navigated the tricky but beautiful atolls of the Tuamotus and explored the diverse lagoons and mountains of the Society Islands. In the summer of 2015, they concluded their eight-year cruising saga in Mo’orea, sold their boat and set off to pursue other goals, including the expansion of The Wirie, which is much easier to do from land than from the middle of the ocean. They are currently house and pet sitting throughout the U.S., combining comfort, unlimited Internet, remote jobs, adorable dogs and alternating surroundings until the next adventure presents itself.

OV: How do you approach the subject of safety? Has your experience sailing offshore affected your thinking on safety?

LC&MK: Mark and I were always very conservative before setting out on long trips and meticulous when it came to our boat. We took our own and our dogs’ safety seriously. We carried up-to-date flares, fire extinguishers, life jackets for four people and two dogs, smoke and carbon monoxide detectors and a storm jib. We inflated our personal life jackets on occasion to check them for issues. Because of the design of our catamaran, we had six different watertight bilges so we invested in a big-capacity bilge pump that we could easily move and plug in to pump out all of the bilge compartments. We had water alarms in every section that didn’t have an automatic electric bilge pump. We studied the weather forecasts in depth before leaving the harbor on a long journey. We wore our life jackets during the day when it was rough out and always at night on passages. During longer trips, we also tied jack lines around the boat and tethered ourselves in at night to give the off-duty person peace of mind. On the ocean, we never left the cockpit without being tethered to the boat.

Before every trip, long or short, Mark checked the engines. The main difference with offshore passages was that we prepared Irie more extensively. We would test all our equipment, go over the engines and the steering gear in detail, check our standing and running rigging, test our communication devices and make sure that all our navigation systems were working. We had spare parts for anything that could fail, including an extra autopilot before crossing the Pacific Ocean.

|

|

Irie and crew sailing from Raiatea to Huahine, Society islands. |

|

Liesbet Collaert |

Over time, you know all the quirks about your boat and what needs to be checked more often. The air intakes of our engine rooms allowed water to come in when the seas were rough on a certain point of sail. We took precautions by taping them up on long voyages. Mark recorded all engine maintenance and scheduled replacements. We did everything ourselves, learning a lot about our boat in the process. We carried books on electrical systems and engine maintenance, plus manuals for our 18-hp Yanmar engines. The Internet, and especially “how-to” videos, came in handy as well. We hauled out annually to treat Irie’s bottom and to inspect the underwater ship, sometimes replacing thru-holes or working on the sail drives. We had use of three different anchors, which were each deployed in particular circumstances. When sitting out Hurricane Ike in the Dominican Republic, we were tied off to the mangroves with three anchors on one side and five lines to shore on the other.

OV: What planning have you done for possible medical emergencies? Did you receive any medical training before you began voyaging?

LC&MK: Apart from Mark doing one CPR course years prior, neither of us had any medical training before we moved aboard. We carried an extensive first aid kit with antibiotics, gauze, all types of bandages, cream, burn supplies, cold and hot packs, etc. We used the Internet for solutions to minor problems and had a dog medical handbook on board. Before heading into the Pacific Ocean from the Caribbean, we acquired a satellite phone and had phone numbers available for emergencies. We were both relatively young while cruising. Because of our age and health, medical training was not a major concern to us. Accidents and emergencies do happen, however, as we came to experience when Mark was diagnosed with cancer in Tahiti. We flew back to the U.S. for surgery and treatment.

OV: What type of life raft do you have? How often do you have it serviced?

LC&MK: None and never. When we started doing longer trips, we decided to invest our money in the boat, its preparations, extra spares and additional communication equipment. Finances didn’t allow us to spend thousands of dollars on a life raft.

OV: What do you have in your abandon-ship bag?

LC&MK: We had two grab bags. One was filled to the brim with water and granola bars, while the other contained a small first aid kit, mirror, basic fishing gear, toilet paper, our spare hand-held VHF radio, scissors, a tarp, a fleece blanket, two hats, sunscreen, rope, a knife, binoculars (small set), sunglasses, two plastic cups for drinking or bailing, hand-held flares, a small compass, a notebook and pens, one flashlight with extra batteries and one manual flashlight with a push mechanism. Many items were packed in sealed Ziploc bags or Tupperware containers that could have other purposes as well. We also put our PLB and hand-held GPS in the bag before every passage. On our “ready to grab when abandoning ship list” were the logbook, satphone, flare gun and additional flares.

|

|

Befriending a Tiki statue on Tahiti. |

|

Liesbet Collaert |

OV: Do you have survival suits?

LC&MK: No. We mainly sailed in the tropics.

OV: Do you have an EPIRB, PLB or a tracking device like a SPOT or inReach SE?

LC&MK: We had one PLB. We didn’t carry satellite tracking devices, but we used our Inmarsat satphone to send position reports. It kept family and friends abreast of our current location and could be used to send emergency information. We would have grabbed it when needing to leave ship. Our satphone represented an integral part of our safety.

OV: Do you have an AIS unit on board?

LC&MK: We had an AIS receiver on board, which we acquired in 2011 in St. Martin. It was part of a newly purchased VHF radio. In today’s day and age, a receiver is standard equipment. As far as the transmitter goes, prices are more reasonable now and we would consider buying one for our future boat. The receiver had many advantages for us. It made life easier when calling big ships, knowing their names, tracks and ETA. We still used our radar intermittently because not every boat has an AIS transmitter.

OV: What types of weather data do you use when making an offshore passage? How do you gather weather information?

LC&MK: We used weather GRIB files from SailDocs (free service). We sent email requests and they returned the necessary information, or we established a schedule to receive updates and reports. We also obtained NOAA offshore weather report texts put together by humans. We used our satphone to retrieve all this information when voyaging.

While in the Caribbean, we listened in on Chris Parker’s weather reports with our $100 portable SSB receiver. On passage in the South Pacific, we could also hear the current weather status and locations of our peers. During that 21-day crossing, we had the contact information of a New Zealand weather guru. We received his weekly emails and contacted him about a nasty cold front coming our way on one occasion. It was a resource we didn’t use until there was a concern. We gathered all our weather information electronically. We looked at this data twice daily — and, when getting ready to go on a passage, four times a day.

|

|

Working as a team while hoisting and trimming the main on Irie. |

|

Liesbet Collaert |

OV: Do you use a weather routing service?

LC&MK: No. We had contact information for weather routing services or individuals in the regions we were sailing, so when we found ourselves in a weather situation we didn’t understand very well, we had a means to contact experts and use their services, if needed.

OV: What types of safety gear do you plan to purchase and why?

LC&MK: On our future sailboat, we wouldn’t change much. We would probably add an AIS transmitter and a third reef point to our mainsail. If your boat can accommodate three reef points, having a deep reef in your main is a good safety feature and we often wished we could reduce sail a bit more during squalls. If money was not an object, having a life raft would be nice, despite the inconvenience of needing to have it serviced often, which is impossible to do in remote areas. I think we would start with acquiring a PLB for every person aboard and an EPIRB for the boat.

While having many gadgets might be attractive (when nothing breaks!), we like to keep our systems simple, so we don’t need extra spares, knowledge, dependency and time waiting for replacement parts.