In the September 2013 issue of Ocean Navigator (#212) I wrote about two of our four trickiest passages during our five-year circumnavigation: 1) up and down the Strait of Malacca, and 2) along the “Wild Coast” of South Africa. The other two, in and out of New England, and in and out of New Zealand, I’ll discuss here.

New England to Bermuda and the Caribbean

The trip coming and going from New England, despite its relatively short distance, can be one of the more challenging you’ll encounter anywhere in the world. The combination of the Gulf Stream crossing and rapid weather changes coming off Cape Hatteras combine to make this passage one that you must plan and time carefully. Typically if you are sailing south, the best time to leave New England is late fall — end of October to early November — after the hurricane season is over but before the strong northerly gales start to build. Likewise, coming back north in the spring, the hurricane season begins in June so it’s best to make your trip back across the Gulf Stream before the end of June to be on the safe side.

We left Maine on Oct. 21 on the back end of a nor’easter and we arrived home again on June 20 five years later, on a flat, calm, crystal-clear spring morning. Departing, we flew down the coast toward Cape Cod with a strong northwest breeze on the starboard quarter and we kept that good wind almost all the way to Newport, R.I., when we got hit with an even stronger norther that blew us into Block Island for a brief respite. This leg, reaching as far south as the Chesapeake, was the coldest passage we experienced on our entire voyage. We were happy to have a good supply of hand-warmers aboard to stuff in our boots and mittens.

Cape May was the spot where we first got to test our new Fortress anchor that, combined with the half-inch mooring chain we used between the anchor and our rode, gave us plenty of good holding ability. We watched several other boats drag near us during a 40-knot gale that lasted several days. We often found slick ice on the deck in the mornings. It wasn’t until we finally crossed the Gulf Stream that things began to warm up a bit and we found ourselves, surprisingly, in shorts and t-shirts.

|

|

A flying fish found on deck at dawn, a common sight in the stream. |

We used Ken McKinley of Locus Weather out of Camden, Maine (www.locusweather.com), as a weather router for this first leg, and his initial routing plan and regular updates were very helpful. We didn’t know enough at the time not to take his counsel absolutely religiously so when Ken (and his then Gulf Stream specialist partner, Jenifer Clark) told us to turn left or right 10 degrees, we obeyed. Sometimes this helped and sometimes not. The combination of his attention to what’s going on aloft and her expertise with what’s happening in the stream itself is, theoretically, a terrific collaboration — and for many Bermuda racers, has helped give them a decided edge. The level of detailed info can cause you to try and take advantage of or avoid every possible eddy and vagary out there, which means you can end up wasting a lot of time messing around in a part of the ocean best navigated as quickly as possible.

Short hop shakedown

We chose to do a bunch of coastal hops as far south as Norfolk, Va., in order to give us the chance to deal with last minute shakedown issues. We’d not sailed our Montevideo 43 Bahati offshore since we’d brought her north from Annapolis a year before and we wanted to test both her and our own capabilities again before biting off any passages longer than an overnight. Bahati had received so many changes in her systems and rig that it took us nearly a year to get comfortable with them all. This is not unusual with a new or refit vessel, so it’s good to plan for a somewhat halting start if your boat falls into either of these categories. It wasn’t until we got past Panama and had sorted out the last big electrical bug in the system that we felt confident enough to head across 3,000+ nm of open ocean.

|

|

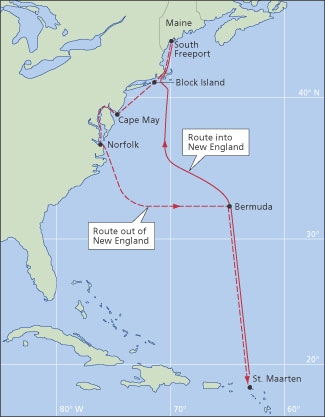

The routes out of and into New England, one of the four tricky passages Nat Warren-White experienced on his circumnavigation. |

|

Ocean Navigator Illustration |

The ride from Maine down to Norfolk was relatively uneventful despite the bone-chilling temps and strong winds we faced leaving home. We arrived in the Chesapeake confident that Bahati would stand up for us in any conditions we might face. We set off from Norfolk right after a deep low passed through, which had caused problems for a number of the annual Norfolk-Caribbean Rally vessels who left just before us on a pre-ordained schedule.

Our initial first stop was St. Maarten, the spot where the Windward Islands turn south, and our first few days offshore set us up nicely for a 10- to 12-day run straight down there. In the end, due to a couple of tricky weather systems waiting to jump us after we crossed the Gulf Stream, our first real offshore passage turned into a record-breaking 12-day detour to Bermuda. Who would’ve guessed?

This 600- to 700-nm passage should take six to seven days tops, but it can often take longer depending on what’s going on with the Gulf Stream and weather en route. When we realized at day nine that we had to make a difficult decision if we were to get our four crewmembers home for Thanksgiving (something we’d foolishly promised them when they agreed to join us), we were about equidistant between Bermuda and the Bahamas. We knew we’d need at least another six to eight days to get to St. Maarten.

|

|

The author’s brother Ben in 40 knots off Cape Ann on arrival back in New England. |

Bee-line left

After an all-crew meeting in the midst of one particularly unpleasant rough-and-tumble dog watch, we made the tough decision to turn left and make a bee-line for that tempting tropical isle conveniently planted mid-Atlantic. It still took us another four days to get to Bermuda, but the sailing was a bit easier with a better slant on the wind and the ultimate landfall was as delightful, if not as far south, as St. Maarten would’ve been. The crew was happy to jump ship and get home for their turkey and we ended up having a lovely Thanksgiving with our new South African friends Neil and Ronel, and their 4 and 5 year-old sons Emil and Peter, aboard Tigre — a boat we’d first met in Portland, Maine, months earlier. We ended up recruiting one local Bermudian crewmember and one friend of a friend to help us with the final jump down to the Caribbean.

We suffered an unpleasant number of course variations and sloppy conditions as we attempted to follow Ken and Jen’s advice. Our hourly log does do it justice, but it’s just plain depressing to read with its testimonies to our slow progress and discomfort. In the end, we would’ve done better to simply stay as close as possible to the rhumb line once we’d crossed the Gulf Stream. As it was, we found ourselves slogging through rough seas and fickle winds a few hundred miles off Cape Hatteras in an area we later learned was less than 25 nm away from the spot where my great-grandfather’s brig, the Ada L White, had foundered on Jan. 30, 1884. One hundred and 23 years later, we were suffering through the same waters under similar conditions. Alas!

Fraught return trip

Our return trip, again via Bermuda, was equally fraught as we attempted to avoid a deep low making up to the east of our rhumb line. This time we used Commanders’ Weather based in New Hampshire (www.commandersweather.com) to help us stay tuned. As we watched the low approach, we altered our course every few hours based on Commander’s good advice, taking a path ever further west trying to avoid the worst of the blow. Eventually, we found ourselves within a couple days of Norfolk again and, with Betsy bound and determined to make it to her nephew’s wedding in Gloucester on June 17, we almost made the same detour in reverse so she could jump on a train in time to be a good auntie. Fortunately, the low passed us by and diminished in intensity enough for us to sneak back across the stream and continue northward. We arrived in Gloucester a day before the wedding. The captain’s good graces saved yet again!

|

|

Crewmember Hillary Gerardi tending jib while en route from Tonga to New Zealand. |

The lessons to be learned sailing this route are many but perhaps the most important is: Don’t assume that the weather report you leave Maine or the Caribbean with is going to hold for more than a couple of days. The truth is that the East Coast of the U.S. is a volatile weather breeding ground and things can and do change quickly.

Combine this reality with the Gulf Stream warmth and strength of flow and you have the perfect ingredients for some very nasty conditions. The rule of thumb is: don’t attempt to cross the stream when it looks like you’re going to get strong winds coming round to the north or northeast. Similar to what happens off the coast of South Africa where the Agulhas Current flows even stronger to the south, when the winds come around they can cause the seas to mount very quickly with treacherous results.

The idea is to pick your departure moment as smartly as possible and then be prepared to adjust your plans a number of times to manage the changing conditions as best you can. There are very few vessels that make this passage, either in or out of New England, without facing at least a couple of days of challenging weather. Like sailing in and out of New Zealand, you just have to be as ready as you can to deal with any challenges that come your way. Though weather routers can be helpful, they are not out there on board with you and cannot see or sense what you are experiencing, so your own weather eye is your best guide, combined with whatever useful data you’re able to download from the GRIB files. Most important, be sure you fully trust your boat and your crew. This renowned stretch of water can easily test both to the limit.

The passage in and out of New Zealand can be equally challenging, and probably more so because it is longer. On our way down from Tonga in the fall of 2007 we waited with a dozen other boats for a decent window to escape from Vava‘u. We had heard lots of stories about how tough this passage can be and we wanted to play it as safe as possible. A decent, if not perfect, window appeared on Nov. 4 and we decided to “exit stage left” quickly before it closed. A half-dozen boats in the fleet stayed behind, not trusting what we were seeing and hearing. In the final analysis, they were the smart ones. The group of boats that left with us later named themselves the “Hindsight Crew” for reasons that will become obvious.

|

|

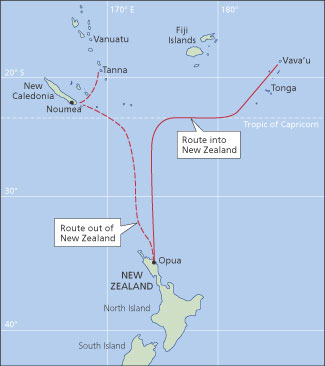

The routes in and out of New Zealand. |

Minerva Reef, a mostly submerged and nearly circular atoll, lies about 400 nm south of Tonga and about 800 nm north of Opua, New Zealand. It’s a good stopping point if it looks like you’ll be running into bad weather ahead.

Bizarre piece of paradise

This is a unique out-of-the-way spot on the South Pacific charts. It’s a strange thing indeed, as we discovered several times off the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, to pull into a spot you’ve found via coordinates on the chartplotter and drop your anchor literally in the middle of nowhere. Many boats end up staying in Minerva for weeks and only get scared away when they see a big low-pressure system heading their way. It’s a bizarre piece of paradise.

We stayed in twice-daily contact with the dozen or so other boats via an SSB “sked” (scheduled virtual rendezvous) who had also decided to carry on and try to get to New Zealand before the low nailed us. This kind of regular contact — sharing local conditions and updated weather information — is a blessing on a long passage. You’re reminded you’re not quite as alone out there as it often feels.

In this case, our friends Katie and Jim, the self-ascribed “inmates” aboard Asylum, a Tayana 38, became our net “hosts” during this prolonged passage. They did a great job of keeping our spirits up by challenging us to come up with poems and songs to share on the air each morning and evening. When all 12 boats finally managed to land safely in New Zealand, we had a “Hindsight Club” shoreside reunion at the Opua Cruising Club during which many of us shared the creative results of the “deep low muse.” What should have been at most an eight- to 10-day passage turned into 14 days for us, and we were not the last to arrive!

|

|

Josh Warren-White at nav station during Bahati’s Tonga to New Zealand passage. |

Sent further west

We chose to use Bob McDavitt, long-time trusty Kiwi router, (www.metbob.com), to help us strategize our route and timing on this leg and he proved to be a good mentor. When we later met him in person, he apologized profusely for taking us so far out of our way! En route, as we saw conditions changing, we checked in with Bob for daily updates via SSB and satphone. He always got back to us quickly with new coordinates to help us find our way around this wayward anti-cyclone, which kept drifting further west. In fact, we really owe it to Bob that we were not slammed as badly as some of the boats ahead of us. Bob kept sending us further west to try and avoid the most dangerous quadrant of the low, the southeast corner in the southern hemisphere. His goal, which quickly became ours, was to see if we could get around behind it. By the time we finally were able to turn south again and get back on course toward the North Island of New Zealand, we were closer to New Caledonia than we were to Opua.

This scenario is strikingly similar to what happened on our way back up from the Caribbean to New England on the final passage of our circumnavigation. In both cases, the length of our voyage was extended considerably as a result of the choices we made, but thankfully so! We carefully avoided dangerous weather by heeding the advice of experts ashore.

Josh, our then 26-year-old son, became our onboard de facto weatherman during the run down to New Zealand. He brilliantly and faithfully managed our communications via SSB and satphone several times a day and he was able to share the information he gathered from Bob McD with other boats on the “sked.” Josh’s article, “Weather Communications,” (ON #172), covers the technology we had at our disposal.

|

|

A few of the twenty-something crew that helped out during various legs of the circumnavigation. |

At our most nervous moment we found ourselves in what we judged to be the absolute dead center of the low: the “eye.” We knew where we were because the winds, which had been blowing a good 40 knots from ahead, suddenly stopped dead. The water flattened out and looked like boiling lava, small rippling dark gray waves spreading as far as the eye could see. We all sat in the cockpit and stared, hardly believing that the wind and seas had slacked so suddenly and completely.

Within an hour, we could hear the wind and rain picking up again, but this time coming from the opposite direction. When we were hit by the new barrage, it came on even stronger than before but from behind — a true blessing. We quickly adjusted the sails, slacking everything off, and screamed on into the night with winds rising again to nearly 50 knots and the seas gradually increasing to 12 and 15 feet. We laughed as we picked up speed again because somehow we felt we were on the other side and headed out the “back door” away from the worst of it, right in line with what Bob had predicted. By dawn, less than eight hours later, the wind had eased and we were able to resume our course due south directly toward New Zealand.

Sail wrestling

At the height of this storm we blew out the clew on our new yankee jib. Josh and Tim wrestled the wildly flapping sail below and replaced it with our heavy old 150 deck scraper — not an easy job. They looked like a couple of cowboys on top of a feisty young steer up there on the foredeck. I was glad they were clipped in and happy it wasn’t me! Then Tim got out the palm and needle and proceeded to mend the broken yankee. We did not use it again until we had it professionally repaired in Opua, but we knew it was available if needed.

On the subject of “clipping-in”: we make it a rule that everyone clips in, even in the cockpit on watch at night, unless it’s flat calm. You never know when a rogue wave will come out of nowhere and hit you. We have stainless jack lines in the cockpit as well as webbing on deck so that no one has to leave the safety of the companionway or cabin without something to clip on to.

|

|

Nat Warren-White, affectionately dubbed “Capt. Biscuits” by the crew, sorts out a troll reel. |

On our way out of New Zealand over a year and a half later, Tim returned to Bahati bringing his girlfriend (and now bride) Meghan to help us find our way back into the tropics, this time via New Caledonia and Vanuatu. Tim and Meghan both proved to be the kind of gung-ho, positive shipmates one can only wish for on these tougher passages: ready, willing and able, and always with a good sense of humor to match.

On our exit trip out of New Zealand, which began on May 4, we jumped on the back of a fast-moving low thanks to good local coaching, and managed to get almost all the way to Vanuatu without experiencing any really difficult weather. The first two days were a bit “wild and wooly” but nothing Bahati and we couldn’t easily handle. Compared to the trip down, it was a cakewalk.

The long and short of this tricky passage is that patience prior to departure and en route pays off. Like the New England run, you are bound to find a strong front or two along the 1,000+-mile route. It’s unavoidable. And like the U.S. Eastern Seaboard, this stretch of water from the northern tip of New Zealand to the nearest tropical islands on the other side of the Tropic of Capricorn is a weather breeder. Caution, good preparation and a sense of humor are the keys to a safe and enjoyable passage whether heading in or out.

Nat Warren-White is currently working as a management consultant while scheming his next voyage, possibly to Norway.