|

|

The Ian-Frese’s Tayana 37 Anna negotiates the snaking, deepwater channel to La Chunga up the Rio Sambu. |

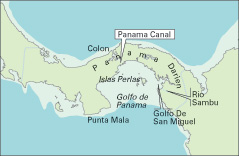

We had decided months ago, during the stormy wet season, to visit eastern Panama’s Darién province aboard our Tayana 37, Anna. Darién is a remote region of inadequately-charted snaking river systems, heavy jungle, mountains and isolated indigenous tribes. It contains a plethora of tropical wildlife, ranging from venomous frogs in the jungle lowlands, to tigers on the prowl in the higher elevations.

Located approximately 100 nm from the Panama Canal, Darién is invitingly close by. From the Perlas Islands the approach to the Gulf of San Miguel and Darién’s jungle-river tributaries is only 35 nm to the east-southeast. Darién is rarely visited by voyaging boats. And there are a number of reasons for this, one of the more serious being the lack of reliable navigational aids. Equally challenging are inadequately surveyed mudflats and jungle rivers with complicated and fast-moving currents. The rivers also have large, drifting tree trunks — which refuse to follow the rules and stay to the outside of the river’s curves. But these can be negotiated successfully with a little advance planning and a willingness to clear log jams off the bow. We decided it was definitely worth the effort to visit Darién, and its unique inhabitants, if you plan to be in, or pass through, this part of the world.

|

|

Alfred Wood/Ocean Navigator illustration |

|

The Darién province lies east of the Panama Canal and the Perlas Islands. |

We departed the Perlas Islands at 0800 and arrived at Punta Garachiné, gateway to the Gulf of San Miguel and the Darién province, at 1530.

We anchored close to the wooded shoreline for the evening and began our fast drift upstream the next morning, at 1100, when the tide was flooding and in our favor. It wouldn’t matter whether our bottom was dirty or not, with the narrow, winding rivers that cut through the jungle, the water flow would be fast — assuming we timed it correctly, we would get a nice lift upriver.

Challenging rivers

Part of the challenge of Darién, aside from its innate wildness, is that the rivers are swift and the nautical charts are all but useless. Navigating inadequately charted waters with unreliable soundings, often comes down to guessing the precise location of the deep-water channel. The shoals and mudflats are extensive in Darién, and they can shift position when the currents, rains, and mudslides are heavy. The closest tidal current tables are 50 miles away, and do not necessarily agree with the river current speeds and times of slack water.

The ebb current can average four to five knots in strength, and the time of slack tide doesn’t correlate with the turn of the tide, from high to low. We have found that slack water is off by about three hours, from the turn of the tide to ebb. The flood tide slack, on the other hand, appears to occur close to the turn of the tide. In the Gulf of San Miguel, into which all the jungle rivers in Darién pour, the tides and currents seem to be in sync, that is, the turn of the tide occurs close to slack water, in both directions…but not necessarily everywhere. So it is a non-trivial system of fluid dynamics. The indigenous fishermen know the waters well, and they move effortlessly, using the ebb and flood tidal currents to their advantage.

|

|

A local man uses the Rio Sambu’s four- to five-knot current for a fast ride downstream. |

Another challenge is that the bottom of the rivers here are typically composed of slick, silty mud. If a big log or two or three gets caught up in ground tackle chain, an anchor can drag in a fast current. And dragging anchor in a four- to five-knot current, on a narrow, winding river in the pitch black of night is not at all acceptable. As if that wasn’t enough, at the jungle’s edge, where it meets the river, mudslides deposit tree trunks and tree stumps and reeds and weeds into the fast current, and frequently this debris ends up in a tangle at the waterline with the chain and bridle. This can often be cleared by coaxing the logs off the bow and sending them downstream with a sharp-ended boat hook (the logs are slick and a sharp steel boat hook can dig into a log and gain some traction).

Occasionally a log can be cleared by turning the wheel while at anchor, and shifting the bow to port or starboard until the log jam wiggles free. Another method is to jump in the dinghy with outboard engine at full throttle (just to keep up against the current) and tie a line around the log, trying to pull it off of the anchor chain, bobstay, and bridle.

Jolted awake

Once when a 30-foot log with an 18-inch diameter jammed the bobstay at 0430 and jolted us out of a sound sleep we tried another technique. We turned on the engine and motored forward a few feet, while still anchored, and then quickly reversed gears. The idea was for the log to slip out and away from the bow before the strong current pinned the log sideways to the anchor chain, bridle and bobstay. If that happened it would likely collect more flotsam and jetsam. Steering to port or starboard, at anchor, while reversing gears in a four-knot current at night, is part of what makes this area seldom visited by cruising vessels!

|

|

Fishermen in Darién use crude workboats, but it doesn’t hinder their ability to take in a prodigious catch. |

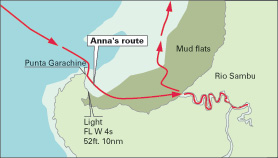

Anna crossed the murky waters of the mudflats, a five-mile strip of slick mud that zeros out at dead-low tide. The flats separate the deeper waters of the Gulf of San Miguel, from the entrance channel at the mouth of the snaking Rio Sambu. The idea, when crossing the mudflats, of course, is to stay in water deep enough so as not to become grounded. To do this, it is necessary to leave on a rising half-tide of at least nine feet (for Anna’s six-foot deep keel), which would provide some leeway for an uneven bottom contour. On a rising tide there is an opportunity to float away within a few minutes if Anna’s keel were to accidentally touch bottom and stick to the mud. The closest we came to grounding was to glide within one inch of the bottom. Clearly we were lucky, but had we been grounded, it would not have been for long. Grounding on an ebb tide would have been a different story. Anna would have been lying on her side, at a 45-degree angle until the flood tide filled in, six hours later.

Once across the mudflats, near high tide, the mouth of the Rio Sambu grows deeper and takes on the color of a café con leche. The current kicks into high gear just beyond the entrance mouth, where the water becomes increasingly deeper. Since the charts are inadequately surveyed for this area, the electronic chart showed our boat crossing land repeatedly as we snaked our way upstream. We went for 10 nm, to the indigenous village of the Embera tribe, at La Chunga.

One thing we did to compensate for the lack of accuracy and detail in the charts of the area was to download satellite imagery from Google Earth of the Darién province, especially the entrance channel to the Rio Sambu, the mudflats, and shoals. We then overlaid these satellite images of the region over our electronic nautical charts. By doing so, we can often see channels and shoals more accurately than by simply relying on outdated nautical charts.

Guessing the deep water

Of course, the shoals can drift if not dredged (and they are definitely not dredged in the Rio Sambu). So it’s still, to an extent, an educated guess as to where the deep-water channel resides. We use a nice hack called GE2KAP for converting Google Earth satellite imagery to .KAP files, which can then be overlaid in our navigation browser, OpenCPN. The .KAP files are installed and read from the same directory as the charts. Routes can be laid down over the Google Earth image and then observed over the transparent nautical chart. It’s a slick way to double check a plotted route or waypoint, on a dated, or poorly surveyed nautical chart for accuracy. Some of today’s existing charts are based on surveys completed decades ago, even 100 years ago.

|

|

Alfred Wood/Ocean Navigator illustration Anna’s entry and exit routes across the mudflats at the entrance to the Rio Sambu. |

We did make it up the Rio Sambu to La Chunga without incident, arriving on New Year’s Eve. We settled into a black, starry sky overhead, with the silhouette of a profoundly-quiet jungle and mountainous terrain in the backdrop, barely illuminated by a low sliver of moonlight. A fast, bubbling current and an endless stream of drifting logs kept us company throughout the night. When daylight broke we heard the unmistakable sounds of the Rio Sambu. Parrots chattered and squawked and flew in pairs, high above the tree canopy, frenetically flapping. The bird calls of the Oropendula (golden pendulum tail) were one of our favorite; their call is similar to the sound of a heavy rock plunging into a glassy pond, without a trace of a splash: a deep…glunk…glunk. The young toucans sounded like washboard, percussive instruments. And the birds of prey rapid-fired their screeches. The owls hoo-hooed, regardless of the time of day. There were snorts from what could have been a boar rustling through the giant banana leaves.

The lowlands surrounding the village of La Chunga are home to crocodiles, boas, venomous frogs, lizards, and sloths. The nocturnal creatures include giant anteaters and bats. And in the mountains, a three-hour trek from the village, howler monkeys work themselves into a frenzy, and tigers are on the prowl.

In fact, the only mode of transportation here, in La Chunga, on the Rio Sambu, is on foot through the mountains and lowlands, or by dugout canoe, up and down the rivers, going with a favorable tide. We’ve seen some domesticated animals, like horses for hauling timber, chickens for fresh eggs, and an occasional parrot perched in the rafters of the open huts.

The indigenous Indians of the Rio Sambu consist of a number of tribes in villages distributed along the length of the river and into the jungle and mountains. They fish, grow their rice in paddy fields between the lowlands and the mountains, grow corn, collect rainwater, weave baskets, string beads, carve intricate hardwood sculptures of birds and reptiles and decorate their bodies with geometric, black ink designs (they get their ink from the colorful berries and plants that grow in the jungle surrounding their thatched-roof stilt huts).

Their use of electricity is limited to a few donated solar panels, which most notably run two small (probably donated) LED lights. These illuminate the bare bones schoolroom. Aside from open woodstove cooking fires, the only other illumination is the occasional flashlight.

The kids appear to be a happy, carefree bunch. They run the jungle paths at full speed and jump off high cliffs into freshwater swimming holes, which double as the laundry and fish-scale cleaning stations.

The Embera people

The Embera people we met at La Chunga were friendly, welcoming and genuine. They offered us the chance for some simple conversation (their language is Embera, which is not exactly the same as Spanish, but they understand and speak enough Spanish to get the point across). We would say something in Spanish and they would understand what we said, and then teach us the Embera terminology.

|

|

Stilt huts in the village of La Chunga are homes used by the local Embera people. |

At the end of the day, before darkness set in, we returned to Anna, typically loaded down with gifts of food, such as banana stalks, coconuts, and sugar cane (a sweet, juicy treat to crunch on, while on the trail back to the river), or fresh eggs from the coop. Or if we were on the boat, we might be visited by a river fisherman who’d kindly bring by five or six fish for us to clean and cook.

After our marvelous stay, we departed Rio Sambu on a high ebb tide and worked our way north, across the mudflats, en route for Isla Iguana and Isla Iguanita, some 21 nm to the north-northeast. We arrived at 1300, dropped the hook in 17 feet of opaque, silty, jungle-river water runoff. We were now in the northwestern sector of the Gulf of San Miguel, two miles off the Rio Congo.

Fifteen minutes after our arrival, a black cloud descended over the islands and a squall blew through. It rained, and trickled fresh water into our rain-catching system. We’ve caught enough rainwater in the past six months to completely eliminate the need to buy filtered water or make water with our small, reverse-osmosis system. We love catching rainwater, and powering our electric demands, for the most part, with solar and wind power.

There was no one at this anchorage except for a couple of small fishing vessels. But that came as no surprise. There are but two seasons here: the off season, and the off season. I guess you might say that we were in between seasons.

Good forecast for return

After a couple pleasant days and nights at Islas Iguana and Iguanita, we downloaded the weather, by SSB radio and Pactor modem, and determined the forecast was good for returning to the Perlas Islands.

|

|

Cat Ian-Frese admires a 40-inch yellowfin tuna caught on the sail returning to the Perlas Islands. |

It was calm at sunrise, and as we began to haul in the anchor it seemed a bit heavy. Of course, we couldn’t see anything below the murky surface, but then a large array of rebar hooks in the pattern of a giant starfish, welded onto a long shaft, dangling from a shackle and a few feet of rusty chain appeared. It was wrapped around our chain and took some engineering and about 30 minutes to disengage. Darién, it seemed, didn’t want to see us leave, but Anna wouldn’t have it, and as soon as we cleared our anchor and chain, we released the auxiliary rebar anchor (which no doubt belonged to a Darién fisherman) and said goodbye, as Anna chugged happily out to sea.

We set a course to the Perlas Islands, dragging a 100-foot-long fishing line, a hand line with a four-inch cedar plug attached to the trailing end. When Anna found deeper water we looked back and saw that we were towing a pretty large, glistening fish. We hauled it in, hand over hand, and got it up to the rail. Too heavy and big to lift over the side with bare hands, we grabbed our large gaff hook and snagged the beauty. We admired it for a while before getting down to the business of knifing off its football-sized head and slitting open the undersides. It was a 40-inch yellowfin tuna. One of the largest we’ve ever taken in with our hand lines. And its impressive bulk and rich, deep-yellow tail fin were only matched by its exquisite taste.

————

Rich and Cat Ian-Frese have spent the better part of the last year on the Pacific side of Panama and are preparing to depart for Ecuador, Peru and Chile, on Anna, their Tayana 37 cutter. Leaving the lightning storms behind is their current priority.