Cruising sailors are looking for more performance from their boats and sails and over the last few years there has been a trend toward high-tech disguised, in some cases, as low-tech. Take carbon fiber masts, for example. There are now numerous traditional looking yachts that have a carbon mast and boom covered in a wood veneer or even just painted to resemble wood. To the unsuspecting eye these spars look as if they are made from wood.

The same is true with hull construction. Boats are built out of carbon and then painted to look traditional. Sailmakers are doing the same thing. Call any sailmaker and they will tell you that around 80 percent of their voyaging customers are still buying Dacron cross-cut sails, but it’s the other 20 percent that are pushing the edges with high-performance fabrics and sophisticated engineering and that percentage, while still relatively small, is growing every year. Often this trend is barely noticeable. A quick glance at a suit of sails and you might think that they are just plain old Dacron sails, but hidden between layers of laminate is some very sophisticated engineering.

There is a very real advantage to having high-tech sails for voyaging. If you measure the life of a sail by how long it holds its aerodynamic shape as opposed to how long it holds together, then you are going to get a longer life out of a sail that is highly engineered and built using high-performing fibers. The additional upfront costs may indeed save you money in the long run, but that’s not the only reason for considering something more exotic for your sails.

|

|

Photos above and below show sails built with Ullman FiberPath Enduro fabric. |

|

Courtesy Ullman Sails |

For all boats there is a need to reduce heeling and pitching as much as possible and the way to do this is to reduce weight aloft. A membrane sail built from a blend of carbon and Vectran will be about 30 percent lighter than a sail built out of Dacron. A hundred feet up that weight difference translates noticeably into how the boat sails. With the lighter sail there is less heeling and more importantly, there is less pitching. Constant pitching over the duration of a long passage is very fatiguing on the crew, so any way to limit the amount of pitching is good for your crew and an overall performance gain.

Easier to handle

The other advantage of high-tech sails, other than the obvious increase in boat speed which in turn reduces the amount of time spent at sea, is that because they are much lighter than conventional Dacron sails they are easier to handle. It’s easier to furl and unfurl a headsail as well as to take in and shake out a reef. The sails are easy to manage when hoisting them for the first time and take up much less room when stowed below.

Another noticeable advantage is that high-tech sails are able to hold their shape through a much broader wind range meaning that you will end up reefing less and also being able to carry a headsail through a wider range of wind conditions.

There are four distinct parts to a high-tech cruising sail: Fabric engineering is a key component; the overall sail engineering and construction is also important; the size and configuration of the sail can be a key factor; and the individual fibers used in the fabric are at the heart of a high-tech sail. Let’s look at each area remembering that there is some overlap. A membrane sail, or string sail as some like to call them, combines both the sail engineering and the fabric engineering into the same process.

Most cruisers know Dacron and know that it’s used to make a woven fabric usually with the strength in the warp (across the fabric) meaning that the sail is engineered to be cross cut. Dacron is very durable and when treated properly can withstand UV degradation for many years. Its drawback is that it’s relatively stretchy. Some fabric makers will add an exotic fiber to the weave to lend a hand to the overall strength and stretch resistance of the fabric, and while this helps, the result is nowhere near as good as when fibers are used in fabric that is laminated and not woven.

Some of the exotic fibers that are used in sailmaking are Kevlar, Vectran, Spectra (or by its other name Dyneema), Twaron, Technora and carbon. Each of these fibers have their own strengths and weaknesses, but the key attributes that fabric makers, and by extension sailmakers are looking for in a fiber are all the same. Low stretch is very important, good flex, meaning that the sail can be folded and flogged a lot without the fibers breaking is also important. The last attribute is its resistance to UV degradation. A fiber like Vectran is extremely low stretch and can be flexed a lot without degradation, but show it some sunshine and it immediately starts to break down.

Fabric engineering

This is where fabric engineering comes into play. A high-tech sail is usually made up of many layers depending on how big the boat is. There is a Mylar film substrate that lends an overall strength and stretch resistance to the sail. Individual fibers are then laid down on the film each running along anticipated primary and secondary load paths. There can be a combination of fibers each bringing certain strengths to the sail. Sometimes there is a second layer of film and for cruising sails there are almost always light polyester taffetas added to the outside of the fabric. The taffetas are there to protect against chafe and abrasion as well as to protect UV sensitive yarns like Vectran from the sun.

I posed two hypothetical sailors with different sailboats and voyaging plans to a number of sailmakers to get their thoughts.

For Chuck Skewes at Ullman Sails in San Diego I asked him to spec out a high-tech inventory for a 60-foot boat where the owner was going to spend a year sailing locally and then cross the Pacific with his family. Here is what Skewes recommended: “There are many good options for this customer. If he wants the best product available I would suggest that he go with our FiberPath Cruise Enduro product, part of our Voyager Series, for both his mainsail and headsails.

“The FiberPath sail is a membrane sail that is engineered using carbon fibers that are very low stretch and have great durability. We would add light taffetas to the outside of the fabric to add durability so that the customer can use his boat for the year before he takes off on his trip and there will be no discernable degradation in the fabric. The FiberPath sail is very light meaning that it will be easy for him and his family to handle the sails, and because the carbon is very low stretch and extremely strong, they will be able to push the wind range of the sail should they get caught in a sudden squall. A second choice might be our Voyager tri-radial HydraNet Radial. This sail is not quite as high-tech as the FiberPath sail, but it’s still a huge advance over Dacron. The HydraNet Radial is a blend of polyester and Dyneema woven together. It’s not a laminate and the sail won’t be as light as a FiberPath sail or as low stretch, but it’s still a high-performing fabric that is rugged and will last a good long time.”

|

|

Courtesy Doyle Sails |

|

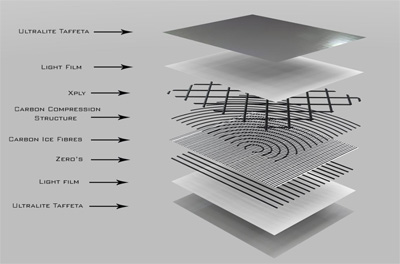

An exploded view of Doyle Sails Ice sail structure that uses a variety of layers enclosed in taffeta exterior skins. |

The second sailor has a 40-foot boat and he was planning on doing a double-handed circumnavigation. He has an adequate, but not excessive budget. “This customer is also perfect for our Voyager Series,” Skewes said. The HydraNet Radial would work the best. The woven fabric can handle the kind of abuse that is certain to happen on a short-handed circumnavigation. Dyneema is white and many traditionalists like white sails. We would also increase the size of the reinforcement patches to give the sail some extra grunt.”

Seam protection

One of the weak areas of all sails are the seams. The thread can get chafed and if they are chafed enough, then the seam could split apart. Skewes is enthusiastic about a new thread made by Gore. “Gore Tenara thread is quite amazing,” he said. “It’s very slippery, resists abrasion, is completely UV resistant, can handle temperature extremes and is not bothered by chemicals. We use their clear thread and we have never had one warranty issue that has been as a result of the thread. It’s amazing stuff.”

Chris Howes at Doyle Sails touted the attributes of their Stratis Ice sails. “This type of construction and engineering is perfect for the family on their 60-foot boat,” Howes said. “The Stratis Ice sails are extremely light and very durable. The load bearing yarns could be a combination of Dyneema and carbon, or if they wanted to save some money they could use Dyneema and Pentex, which is a super polyester and not as expensive as Technora or Kevlar. Our proprietary way of laying up and laminating the sails and the fact that the load bearing yarns come as flat ribbons means we end up with a really smooth, very durable and extremely light sail.”

Stratis Ice is a technology for making membrane sails for racing boats, but if a cruising customer wants a premium product and is not put off by the cost, it’s a very nice option. “For the sailor going double-handed,” Howes said, “I recommend a Vectran laminate. Even though Vectran is very susceptible to UV degradation, you can sandwich the fibers between films that have been treated with UV protection and add taffetas to the outside of the fabric, also treated with UV protection, and you end up with a rugged, low-stretch fabric that would be able to take any of the elements thrown at it during a circumnavigation. We would spec oversized corner patches and add a second ply in the high-load areas of the sail. Because these sails are radial cut it’s easy to have different fabric weights in different parts of the sail.”

North Sails has always been at the forefront of technology when it comes to sail and fabric engineering and Jack Slattery from North Sails Salem has sold numerous high-tech cruising sails over the last two-plus decades. “We have amazing top-end racing products most of which can be spec’d for cruisers,” Slattery said. “The sails need to be engineered with durability in mind and not speed which means that we are not looking for the lightest sail possible, but one that will hold its shape and last a long time. The internal load bearing yarns will still be there to do their job and with judicious engineering we can take full advantage of the fibers and completely minimize their downsides. For the 60-foot boat I would suggest our 3Di technology as it’s the kind of fabric we spec for boats doing the Vendée Globe. Those sailors want high performance, but also need extreme durability.”

No film needed

The 3Di process takes filament tapes that have been pre-impregnated with glue and arranges them on a mold. For the 60-foot boat, Slattery suggested a combination of Dyneema and carbon. The sail is engineered with the yarns running along the load paths of the sail for maximum efficiency. The mold is then put under high pressure which fuses the fibers. The good thing about the 3Di technology is that no Mylar film is involved. Film is good for eliminating stretch, but film also causes shrinkage in the sails which over time distorts their shape. If you think of taking a piece of paper and scrunching it up, you can never get it completely flat again. Same with film. Slattery suggests adding taffetas to each side of the sail for a durable, high-performance sail.

“The sailor going double-handed is a prime candidate for Dyneema paneled sails,” Slattery said. “The Dyneema is woven with the strength in the warp direction, and the panels are cut and the sails assembled in a tri-radial fashion to take advantage of the fabric’s strength. These sails are very rugged and durable, but also high tech because of the Dyneema load bearing fibers. Woven sails cannot delaminate and therefore will be perfect for a circumnavigation.”

All top sailmakers make membrane sails and will spec sails that are quite similar to what these sailmakers have recommended. It’s often a matter of personal preference and a level of confidence in a particular type of yarn or fabric engineering that has one sailmaker recommending one product over another.

One of the good things about racing boats is that the technologies learned at the cutting edge slowly trickle down to the cruising market. Even better, as these technologies become more widely available, the price comes down and while a high-tech sail is undoubtedly more expensive than a basic cross-cut Dacron sail, the cost over the useful life of the sail can often be justified. If you are considering a new sail made from an exotic fabric, remember that it’s how long the sail has a decent shape that counts, not just how long it holds together.

————

Brian Hancock is a circumnavigator, author of seven books and the creative director of SpeedDream.