It’s June, and the hurricane seasons of the central and eastern Pacific and the Atlantic have officially begun. The Pacific season began on May 15, and the Atlantic season on June 1.

Tropical cyclones are not limited to the official hurricane season, though, and this was shown in the Atlantic this year as the first tropical storm of the season (Ana) occurred in early May, before the official start of the season. Ana began as a subtropical storm (meaning some characteristics of a tropical cyclone, but also some characteristics of a non-tropical system) and evolved into a tropical storm before making landfall in South Carolina. It then moved northeast off the mid-Atlantic coast and was absorbed into a frontal system south of Atlantic Canada.

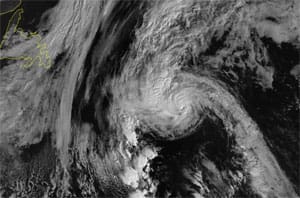

On the Pacific side, not too long after the official start of the season, Andres developed in late May and reached hurricane strength within about a day and a half of its formation. After a couple more days, it became a major hurricane in the tropical waters well to the west of central America, then almost as quickly lost its strength as it moved over colder waters farther to the northwest. While Andres was still a hurricane, Blanca developed and also intensified fairly rapidly, reaching major hurricane status within a couple of days and, at this writing, was just beginning to weaken — although was still a hurricane off the southern coast of Mexico. Neither of these systems is likely to directly impact coastal areas with their winds, but the large swells that are generated will have an effect on coastal waters.

The seasonal forecasts for the hurricane seasons were released several weeks ago, and both forecasts show the impacts of El Nino, which is now well established through most all of the equatorial Pacific. Although El Nino is not the only factor affecting the number of tropical cyclones that will ultimately develop in each basin, research in recent years has indicated that it has a significant effect. On the Atlantic side, the presence of El Nino tends to suppress hurricane formation, and with other factors also pointing toward a quieter season, the seasonal forecast indicated a 70 percent chance of below-normal activity.

In the Pacific, the presence of El Nino is associated with greater-than-normal tropical cyclone activity (not a surprise, since El Nino refers to warmer-than-normal sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific), and the seasonal forecast reflects this by indicating a 70 percent chance of more tropical cyclones than normal in both the central and eastern Pacific regions. The systems that have developed so far are fairly classic eastern Pacific systems, developing rapidly in the waters west of central America, then weakening as they track west and northwest over colder waters. This pattern is likely to be repeated several times through the upcoming season.

Even though the Atlantic forecast is for a quieter season than normal, folks need to keep in mind that it only takes one storm in your area of interest to have a huge impact. This was the case last year in Bermuda, which sustained two direct hits within a week despite the fact that the overall season was quieter than normal. This is the time of year to make sure that you have a plan in place if a hurricane should threaten your location. One of the first stops to put together this plan should be the website of the National Hurricane Center (www.nhc.noaa.gov/). There, you can find the seasonal outlook along with strategies to prepare, and also some information on some new tools available for this season. Continued research in recent years has allowed for significant improvements in forecasting capability, which, in turn, has led to new ways for meteorologists to communicate information to the public in vulnerable areas. Storm surge produced by a hurricane at landfall is often one of the most damaging aspects of these storms, and there are new products that will be tested this year to help determine where storm surge will occur and how severe it will be.

The ability to predict tropical cyclones has never been better, although it is still not perfect. For ocean voyagers, and for those with interests along the coast, it only makes sense to be aware of what will be available to help with planning and decision making should a system threaten your area.