We slipped out of Guaymas, Mexico, in the northern Sea of Cortez, in late October aboard our Tayana 37 sloop Anna. This was only the first part of a 2,500-nm passage from northern Mexico to the Perlas archipelago in the Gulf of Panama. A trip that would take us through the dreaded Gulfs of Tehuantepec and Papagayo with their possible gale-force winds and choppy seas.

There was no room for complacency on this trip, especially in October and November, along the near-offshore route to Panama. Late-season tropical storms, in the northeast Pacific Ocean, developed and spun off into hurricanes along the Pacific coast of Central America; and they were a threat into December.

|

|

Rich and Cat Ian-Frese’s Tayana 37, Anna. |

Offshore or coastal routing

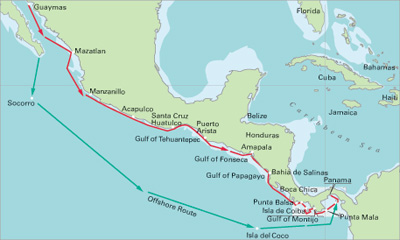

During the season of strong Papagayos (heavy northerlies lasting from December to May) the dangers of the coastal route can be bypassed with a direct 2,400-nm offshore passage from the southwest tip of the Baja Peninsula to the Gulf of Panama. This route would skirt the Gulf of Tehuantepec and the Gulf of Papagayo by as much as 500 nm, off their respective coastlines; both of these gulfs can be ferocious from November through April.

The offshore route, however, has its own idiosyncrasies. In addition to the intermittent tropical storms and hurricanes that track through at the tail end of hurricane season, are the variable winds and counter currents, interspersed with calms and squalls and large, tedious, sloppy seas. This mixed bag of unfavorable ocean conditions during the off season had us pondering the merits of the near-offshore strategy; a route where careful timing of the Gulf of Tehuantepec and the Gulf of Papagayo crossing took top priority.

We weighed the existing weather and sea conditions, computer model forecasts, normal seasonal patterns and anomalies, and then thought about how much of a beating we would be prepared to take when conditions fell apart; and we concluded that the near-offshore strategy, from the northern Sea of Cortez to Panama, was preferable during the months of November through April. But if the weather window at Tehuantepec or Papagayo shut down — and a strong probability existed that it would — then we could get seriously hung up, possibly for weeks or more.

We made three stops en route to the northwest entrance of the Gulf of Tehuantepec. We could wait in Huatulco, Mexico, for good conditions to complete the 250-nm crossing of the Tehuantepec. We would pick up our international zarpe (exit clearance papers) in the Port of Chiapas, Mexico, and continue on to Central America.

Our strategy for crossing the Gulf of Tehuantepec was to skirt the curve of the beach, close to shore, where the fetch of the wind waves across the gap at the north side of the isthmus would have no chance to develop. We could still get hammered by the wind, but it is the progressively larger, breaking seas, farther out, which cause the bigger headache. Cutting across the center of the Gulf, on a rhumbline course to Chiapas, while a bit shorter, is exponentially more risky in the off season.

|

|

Alfred Wood/Navigator Publishing illustrations Inshore and offshore routes from Mexico to Panama. |

|

|

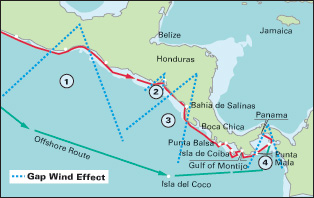

Gap wind areas: 1) Gulf of Tehuantepec, 2) Gulf of Fonseca, 3) Gulf of Papagayo and 4) Gulf of Panama. |

On Dec. 20, a storm warning was issued for the Gulf of Tehuantepec: 50- to 60-knot winds were forecast to funnel through and generate 20-foot breaking seas with a six-second period between wave peaks. It was expected to settle down on Dec. 23, for 48 hours — not enough time to transit before the next wind event was forecast to blow through.

Late on Dec. 23, weather guidance shifted and indicated a 60-hour window opening up on Dec. 24; wind and seas would abate. The tight isobars were easing up in the Gulf of Mexico (on the opposite side of the isthmus) and promised to give Anna an opportunity to push across the Tehuantepec before it closed down once again.

In the Tehuantepec, the gap winds are heaviest in December and January. Both early November and May are considered the optimal times to complete the crossing, unscathed. But contrary to the rule of thumb, we found that November was fraught with storm activity. December, on the other hand, had at least two good weather windows where sailing was a viable option for a good portion of the ride across.

Anna departed early on Dec. 24 to make Chiapas and arrived in 54 hours. We based our decision to go on the concurrence of three GRIB models: the COAMPS, WW3, and GFS. It was a good decision; the models had been exhibiting consistency and accuracy over time, and therefore, our level of confidence in them had been reinforced. We had the predicted head winds, but also a strong current in our favor — Anna zipped along at 7 to 8 knots for the first 80 nm; a very good start. Then the current reversed and we had 2 to 3 knots against us for the next 70 nm — slower going, but we still maintained 4 to 5 knots through the water. The last hundred miles offered us an indifferent current and a light variable breeze, changing in direction from hour to hour. Over the 54 hours it took Anna to complete the crossing, the wind waves and swell were of small to moderate size, and well spaced.

For the 100-nm stretch from Salinas to Solo Dios we rounded the isthmus within four miles of the beach. This would give us the option, if necessary, of coming in just two miles and anchoring in 30 feet of excellent holding sand — to take a rest, sleep, or wait for conditions to ease. We opted not to anchor along the open roadstead as we wanted to put as much distance as possible behind us while good conditions prevailed. We knew that once we made Solo Dios, on the eastern shoreline — about two-thirds the way around the Gulf to Chiapas — the winds would slacken. Even if the forecast fell completely apart, the heavy funnel effect of the gap winds rarely reach beyond Solo Dios.

Our easy crossing of the Tehuantepec was remarkable. We had only one surprise: we were able to use our full, unreefed mainsail and fly our drifter for long stretches.

With the Tehuantepec now in our wake, the toughest leg was behind us — or so we thought, until we met Tehuantepec’s evil twin, the Gulf of Papagayo and the 125 nm of contemptible coastline leading up to it. With weather windows of 12 hours or less, from the well-protected industrial Port of Corinto, Nicaragua, to the windy, but safe haven of Bahia de Salinas, Costa Rica, the coastline would offer no true protection from severe weather and seas.

Gulf of Fonseca

Two hundred nautical miles to the southeast of the Gulf of Tehuantepec, lying at the northern fringe of the Gulf of Papagayo, sits the Gulf of Fonseca. It is vast and beautiful, and it has very strong northeasterly winds, which blow through from December until May — gap winds that resemble the Tehuantepec and Papagayo. And while the Fonseca gap winds are somewhat less intense than that of the Tehuantepec or Papagayo, they are still strong enough to make you think hard about your choice of anchorage for the night.

|

|

Anna anchored off the beach at Isla del Rey in Panama. |

It took Anna 96 hours to complete the passage from Chiapas, Mexico. We slipped through the northwest entrance to the Gulf of Fonseca in 30 knots of breeze, when the 20-mile-wide gap — between mountain ranges — revealed itself. And as dawn broke, in a sheet of pink, we sailed directly into the quiet, protected waters behind Isla Meanguera, El Salvador, and dropped our spade anchor in a small, sandy cove near the fishing village; and quickly fell asleep. The next day we continued to Honduran waters, six nautical miles to the north, before the gap winds kicked up.

The Gulf of Fonseca shares international borders with three countries: El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua. We chose to clear customs in Honduras. The reasons were simple: the clearance procedure was easy, fast and friendly; the international entry, exit, and Immigration fees are all waived for a cruising vessel — unique!

The beginning of the dry season, in Panama, was slipping away from us, but we had time on our side now. The tough part was behind us. It was early January, and we had less than 500 nm to go to reach the western border of the Republic of Panama.

The Papagayo pattern

From January through April the weather forecasts had shown no signs of moderation. We saw the same recurring pattern, day after day, week after week: a six- to 12-hour break from the pulsing, heavy winds and big seas. Weather windows were simply too short to transit the Papagayo in one leap. And it wasn’t as if we hadn’t tried. We made four attempts in two months.

We were stopped dead in our tracks on three separate occasions; each time when we reached the vicinity of the Port of Corinto, 50 nm southeast of the Gulf of Fonseca. Steep, short-period wind waves, directly on the nose, opposed a 2-knot reverse current; added to that was an ocean swell off our starboard beam; a bad combination with a washing-machine motion.

What we got were big, confused, choppy, miserable seas. And close to the coast, where the ocean depths are shallow, the seas grew sloppier, coinciding with the diurnal pulsing of the fierce Papagayo gap winds, which are strongest between midnight and six in the morning.

Analyzing the weather along this stretch of coastline is a challenge; complicated in the off season by unstable weather patterns on both sides of Central America — the Pacific Ocean on the west side, the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico to the east. Land effects, such as downslope winds, gap winds, solar radiation, nighttime cooling, and tropical convection add to the complexity.

Nonetheless, closer to shore is where you want to be, to avoid the significantly heavier conditions farther offshore, in the center of the Gulf of Papagayo — a cone of trouble fanning out to the northwest, up to 400 nm off the Pacific west coast of northern Costa Rica.

|

|

Wind whips up the waves in the Gulf of Fonseca on the Honduras coast. |

Computer models have too little resolution near the coastline of Nicaragua to provide confidence in their raw data. The wind and the waves are constantly reinventing themselves; they can change direction and force from one section of the coast to the next, without warning.

Our plan to reach Panama at the beginning of the dry season had gone up in smoke. We felt there was no virtue in bashing our way farther south until the seemingly endless cycle of pulsing, heavy-weather broke. Besides, we were enjoying slowing down after a string of 48- to 96-hour passages over the last 1,600 nm.

Then a rogue, 36-hour window of opportunity appeared, out of nowhere. And the impossible stretch of coast, from the Gulf of Fonseca to northern Costa Rica, had opened up before us. It was time to go, to break free of the vice-like grip that the Papagayo had on Anna.

We had an excellent 36-hour weather forecast and we had to make 192 nm — the distance between the Gulf of Fonseca, Honduras, and Bahia de Salinas, in northwestern Costa Rica.

A full gale was threatening the tail end of the forecast according to the computer models, which for a change had all been in agreement. Relentless, pulsing, heavy weather had us in its grip. But it now appeared that it was time for our fourth attempt, since arriving at the Gulf of Fonseca, to make northwest Costa Rica, and slip in under the lee of Bahia de Salinas, before the next gale plowed through.

We sailed out of Honduras at twilight and slid right along at 5 to 6 silky-smooth knots, passing the previously unattainable, invisible barrier, seven miles southeast of the Port of Corinto. We made an unthinkably smooth, 192-nm passage to the northern border of Costa Rica in 33 hours. All we had to do now was tiptoe around the corner — the leading edge of the Gulf of Papagayo — some 300 nm from Bahia de Salinas to the western border of Panama, and we were there; two months late, but there, nevertheless.

The wrath of Bahia de Salinas

When we arrived at Bahia de Salinas, the waters deep inside the bay were glassy smooth. The rare 12-knot breeze and small, long-period swell off the starboard bow, which we had on the ride down, kept the waters under control. We could snug up under the lee of Bahia de Salinas, a colossal, empty anchorage with protection from the north, east, and south, and more important, from the fetch of the Pacific swell, which wouldn’t wrap around the open, west-facing entrance to reach the deeply set head of the bay, five miles in. The sea floor was uniform, with 15 to 20 feet of hard-packed sand. Perfect.

|

|

A standing wave forms at Boca Brava in western Panama. |

By late night, however, the breeze had picked up. The Papagayo winds were once again pulsing through the gap at 30 knots. In the anchorage, the east-northeast wind waves built to two feet in just half of a nautical mile of fetch, the distance between Anna and the sweeping, white-sand beach. Whitecaps began to cover the sapphire water. And by the next morning we were in the teeth of a gale — the wind whistled through the rigging and registered a steady 40 knots, with frequent gusts to more than 50 knots. Still, it was remarkably comfortable on Anna, under the lee of Bahia de Salinas.

Our Aerogen4 wind generator was putting out 10- to 17-amps per hour (nominally, we expect to see 1- to 3-amps per hour, in 10 to 15 knots of wind). But wind power is exponential, and when it blows that hard for 10 days, we have energy to burn. Combined with our solar-panel array, which averaged about 5- to 7-amps per hour, during the partly sunny days, we were seeing a total of about 375 amp hours of energy coming in to the battery banks every 24 hours. We could run computers and refrigeration and download weather data from the SSB, and still not come close to running a deficit of energy. Anna’s battery banks were registering full capacity for the entire 11 days we were pinned down at Salinas.

When the wind finally subsided to 30 knots, we continued south on a comfortable broad reach along the outer, western coast of northern Costa Rica, around the first major headland to the Gulf of Nicoya, and then verdant, steamy, Gulf of Dulce, and finally the border of the Republic of Panama.

Out of the Papagayo

We arrived at Punta Balsa, Panama, just across the international boundary line with southern Costa Rica, in the deep black of night on April 14. At 0245 we could hear the surf breaking on the beach close by, but we couldn’t identify any hazards visually (and to be sure, there were hazards at hand), so we made the final approach, very slowly, under electronic charts, depth sounder and radar. We found what we were looking for, what appeared to be a 20-foot shelf of sand, and we dropped our spade anchor. It set well.

When we awoke, after daylight, we took a look around. We could see surf breaks and reefs in close proximity, but our location was perfect and so we decided to stay put an extra day, to catch up on some sleep before continuing, with determined progress, east, into Panama’s western sector.

Ahead lay the Gulf of Panama and the Perlas archipelago, which represented the culmination of a long series of near-offshore passages and open crossings, totaling 2,500 nm and six months; across seven countries, from the northern Sea of Cortez, to the approaches to the Panama Canal, at Balboa.

———-

Rich and Cat Ian-Frese, voyage aboard Anna, their Tayana 37 cutter. They are slowly working their way along the Pacific coasts of North America, Central America, and South America.