In late October, we are currently in the waning weeks of the 2017 hurricane season in the northern hemisphere, and in many ways it has been one for the ages. On paper, the season continues until the end of November, but historically, the more active portion of the season is behind us. This allows us to take a look back and assess the season, and also have a look at how the pre-season forecasts have done.

On the Atlantic side, the forecast issued in May before the official start of the season on June 1 predicted that there would be between 11 and 17 named storms, including five to nine hurricanes and two to four major hurricanes (Category 3 or higher). This compares with long-term averages of 12 named storms, six hurricanes and three major hurricanes. The forecast gave a 45 percent chance of having an above-normal season, a 35 percent chance of a near-normal season and a 20 percent chance of a below-normal season. It is worth noting that when the forecast was issued, one tropical storm (Arlene) had already occurred over the eastern Atlantic in April.

In early August, the seasonal forecast was updated and between 14 and 19 named storms were predicted, with anywhere from five to nine becoming hurricanes, and two to five becoming major hurricanes. The probability of an above-normal season was increased to 60 percent while the probability of a near-normal season was reduced to 30 percent and a below-normal season to 10 percent.

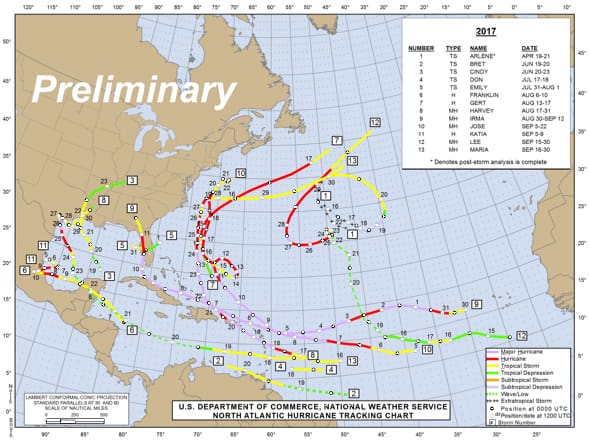

To date, in the Atlantic (as of mid-October) there have been 14 named storms, 10 of which became hurricanes, and six of those became major hurricanes. This means that the number of hurricanes and major hurricanes exceeded the prediction — even of the updated forecast — even though the number of named storms remained within the forecast range and actually on the low end of the updated forecast.

For the eastern Pacific, the forecast issued in May before the official start of the season on May 15 predicted that there would be between 14 and 20 named storms, including six to 11 hurricanes and three to seven major hurricanes. This compares with long-term averages of 15 named storms, eight hurricanes and four major hurricanes. The forecast gave a 40 percent chance of having an above-normal season, a 40 percent chance of a near-normal season and a 20 percent chance of a below-normal season.

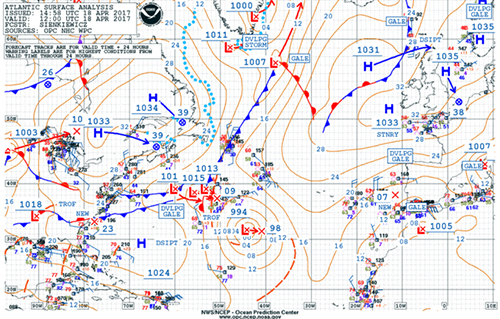

To date, in the eastern Pacific (as of mid-October) there have been 17 named storms, nine of which became hurricanes, with four of those becoming major hurricanes. These numbers all fell within the predicted ranges from the pre-season forecast.

|

|

Source: NOAA, National Hurricane Center (www.nhc.noaa.gov) |

|

Figure 1: Preliminary Atlantic Tropical Cyclone Tracks, 2017 season. |

For the central Pacific, the forecast issued in May predicted that there would be between five and eight tropical cyclones with no delineation between tropical depressions, tropical storms and hurricanes. This compares with long-term averages of four to five tropical cyclones. The forecast gave an 80 percent chance of having a near-normal or above-normal season.

To date, in the central Pacific (as of mid-October) there have been only two tropical cyclones, both of which originated in the eastern Pacific and moved west into the central Pacific region. Both systems were weakening once they entered the region, one entering as a depression and lasting less then one day, and the other entering as a tropical storm and surviving for only two days. This means that the central Pacific season so far has been well below the forecast and also below normal.

The science of seasonal hurricane prediction includes several factors, one of which is the status of El Nino/La Nina in the equatorial Pacific. If El Nino (warmer than normal sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific) is present, it tends to lead to unfavorable upper-level winds for tropical cyclones to form in the Atlantic. On the other hand, the presence of El Nino can lead to decreased wind shear in the Pacific, which is favorable for tropical cyclone formation. For this season, a rather weak El Nino was present early in the season with conditions becoming neutral later in the season. This may have meant that there were no inhibiting factors for upper-level wind shear in the Atlantic, and on the Pacific side upper-level winds were marginally favorable for at least a part of the season.

Sea surface temperatures are also a factor, and these were above normal in the hurricane formation areas in both oceans this season, which was favorable for storms to form.

The seasonal forecasts for both the Atlantic and the eastern Pacific cited these factors, and both forecasts ended up being essentially correct. However the seasonal forecast of the central Pacific was off the mark, and this simply indicates that the factors controlling hurricane activity are still not fully understood.

|

|

Source: NOAA, National Hurricane Center (www.nhc.noaa.gov) |

|

Figure 2: Preliminary Eastern Pacific Tropical Cyclone Tracks, 2017 season. |

For the Atlantic, not only was the season above normal as far as the numbers of systems were concerned, but there were also significant impacts on many different land areas. From Harvey in Texas and Louisiana to Irma in Florida — both of which also impacted islands in the Caribbean — to Maria in Puerto Rico, Nate in Louisiana and Mississippi, and finally Ophelia in Ireland, millions of people were impacted by Atlantic tropical cyclones this season, and a large portion of them will be dealing with ramifications from these storms for months or even years to come.

Figure 1 shows a graphical summary of the Atlantic season through hurricane Maria. Hurricanes Nate and Ophelia occurred after this graphic was produced. Figure 2 shows a graphical summary of the eastern Pacific season through tropical storm Pilar. Tropical Storm Ramon occurred after this graphic was produced.

Equatorial sea surface temperatures in the Pacific have been cooling more recently to the point where climate forecasters are suggesting that a La Nina pattern will prevail through the winter months. If it persists into the 2018 hurricane season, the season could be quite different than this year was. A La Nina pattern is generally associated with an above-normal number of tropical cyclones in the Atlantic and below-normal activity in the Pacific. Of course, as with this season, other factors also need to be considered. Everyone awaits the seasonal forecasts for 2018, which will be issued in the spring.