|

|

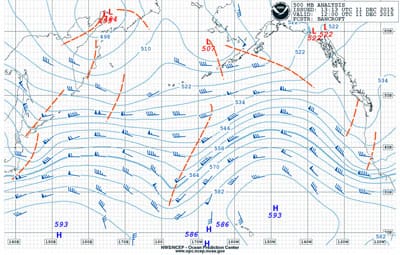

Fig. 1: 500 millibar chart, 1200 UTC Dec. 11. |

As this newsletter is being written, we are not quite halfway through the month of December 2015 — but even so, we can already describe the weather pattern over the North Pacific as very active. In the U.S., this has been manifested by serious flooding and storm damage in Oregon and Washington and significant precipitation in California as well. This has been produced by a so-called “parade of storms” as classified by many media outlets, and the term fits the situation well.

|

|

Fig. 2: Surface analysis chart, 1200 UTC Dec. 11. |

The flow at the 500-millibar level has been generally from west to east across the entire Pacific for most of the month so far with the strongest winds generally in the region between 40° N and 45° N. Strongest winds at 500 millibars are an indication of where the strongest temperature change at the surface is located, and this boundary between warmer air masses with tropical origins and colder polar air masses is where storms tend to form. Waves in the 500-millibar flow give rise to the storms that we are familiar with on surface weather maps, and the prevailing west-to-east flow has sent these storms right toward the northwestern U.S.

For this newsletter, I am going to examine a situation that continues the trend of the active pattern in the Pacific. In particular, we will look at the forecast rapid development of a storm in the western Pacific that will track into the Bering Sea. I’ll look at the 500 millibar charts, the surface charts and sea state charts to get an idea of how this storm will develop and what its impacts are likely to be.

|

|

Fig. 3: 500 millibar chart, 1200 UTC Dec. 13. |

The forecast cycle that we will look at begins at 1200 UTC on Friday, Dec. 11. Looking first at the 500 millibar analysis chart valid at the start of the forecast cycle (Figure 1), we can see the general west-to-east windflow at that level across the entire ocean basin. Some waves in the flow are quite noticeable, and the “troughs” are indicated by red dashed lines. We will focus on two troughs of note near and just east of Japan. These two troughs are like two waves in the ocean that are separate but very close to one another, and they are likely to interfere with each other in a positive manner — that is, they will combine into a larger and stronger trough while propagating fairly quickly east through the flow.

|

|

Fig. 4: 48-hour surface forecast chart, 1200 UTC Dec. 13. |

Looking at the surface analysis chart valid at the same time (Figure 2) we notice that there is a well-developed surface low to the east (or downstream) of the 500-millibar trough. This is a favorable position for the low to strengthen, particularly with a 500-millibar trough, which is likely to amplify. Notice the label “Rapidly Intensifying” on the chart near the low. The central pressure of the low at the time of the chart is 982 millibars — already a fairly strong system — but following the arrow pointing from the low to the “X” east-northeast of the low, we find that the forecast central pressure of the low 24 hours after the valid time of the chart is 958 millibars, a drop of 24 millibars over 24 hours. This tells us that conditions along the path of this low will rapidly deteriorate through this period.

|

|

Fig. 5: 48-hour wind and wave forecast chart, 1200 UTC Dec. 13. |

If we now look at the 48-hour forecast products from this forecast cycle, we find that the system is forecast to become even more intense. First, on the 500 millibar chart valid at 1200 UTC on Dec. 13 (Figure 3), we find that the trough is forecast to move quickly east-northeast and evolve into a strong closed upper-level low over the southern Bering Sea. It will likely catch up with the surface low, meaning that the surface low may be at its peak intensity at this time. Examining the surface forecast chart valid at the same time (Figure 4), we find an extremely intense low forecast to be to the north of the outer Aleutian Islands with a central pressure of 925 millibars. This is an additional drop of 33 millibars over the previous 24 hours, giving a total forecast pressure drop of 57 millibars over the 48-hour period. The forecast for this system rivals a moderately strong hurricane with sustained winds depicted on the chart of at least 85 knots, and its circulation covers a fairly large area.

|

|

Fig. 6: 96-hour wave period forecast chart, 1200 UTC Dec. 15. |

The very strong sustained winds over this large area will generate huge seas, and we can examine the 48-hour wind and wave forecast chart valid at 1200 UTC Dec. 13 (Figure 5) for confirmation of this. There is a very large area of significant wave heights of 6 meters or more forecast with this system, and the highest forecast significant wave heights are shown as 17 meters just south of the western Aleutians. It is important to remember that significant wave height is a calculated average, and that extreme wave heights in a given situation can be up to twice the significant wave height. In this case, that means that a few waves could be 34 meters high, which is more than 110 feet!

|

|

Fig. 7: Surface analysis chart, 1200 UTC Dec. 13. |

The system is forecast to be at near its peak intensity at the 48-hour forecast time, and this can be seen be noting on the 48-hour surface chart (Figure 4) that the arrow pointing north from the low center indicates that the central pressure of the storm will rise to 947 millibars by 24 hours after the valid time of the chart. The effects of the system are forecast to persist for several days though, and this can be seen by examining the 96-hour wave period forecast chart (Figure 6) valid at 1200 UTC Dec. 15. The arrows on this chart show the direction of the dominant waves and the colors indicate the period in seconds. A quick glance at the chart shows that the waves from this storm will impact almost the entire Pacific Basin, extending east toward western North America and south into tropical latitudes. They will not be as high as they propagate away from their generation area, and the periods will become longer as well. The leading edge of the waves can be seen in the abrupt change in period extending from near Hawaii generally northeast toward Vancouver Island.

|

|

Fig. 8: Sea state analysis chart, 0000 UTC Dec. 13. |

As a final step in the examination of this situation, we will check the verification of the forecast. To do this, we will compare the surface analysis chart valid at the same time as the 48-hour surface forecast that is referenced above. We will also look at sea state analysis charts valid 12 hours on either side of the 48-hour forecast (the only ones available). This a good exercise to do from time to time. It allows users of the forecast information to gauge the accuracy of previous forecasts, which in turn will allow for a confidence level in the forecasts in general.

The surface analysis chart valid at 1200 UTC Dec. 13 (Figure 7) shows an intense low in the Bering Sea centered at about 55° N, 176° W with a central pressure of 928 millibars. The position is less than 50 miles southeast of the forecast position, and the central pressure is 3 millibars higher than the forecast value. This is a remarkably accurate forecast given the very dynamic nature of the pattern. The orientation of the frontal boundaries associated with the system is also very close to the forecast. I will leave it to the reader to compare the actual conditions with the previous 48-hour forecast in other portions of the Pacific Basin.

|

|

Fig. 9: Sea state analysis chart, 0000 UTC Dec. 14. |

For sea state, because the full ocean sea state analysis is produced only at 0000 UTC, we do not have a direct comparison with the 48-hour forecast valid at 1200 UTC Dec. 13. Looking at the analysis 12 hours prior to the time of interest (Figure 8) we see a maximum significant wave height of 14 meters south of the outer Aleutians near the dateline. The analysis 24 hours later (Figure 9) shows a maximum of 15 meters farther east along 50° N. Looking back at the previous 48 hour forecast (Figure 5) the location of the forecast maximum was between the two analysis charts, so this was likely a good forecast. The maximum significant wave height on the forecast chart was a bit higher than either of the analysis charts around it, but certainly in the same neighborhood, so the forecast gave a very good indication that the seas would be extremely high in this area.

Examining weather charts like this is an excellent way to learn more about weather patterns in the Atlantic and Pacific, and comparing later analysis charts to the previous forecasts is a good way to keep track of forecast charts accuracy.