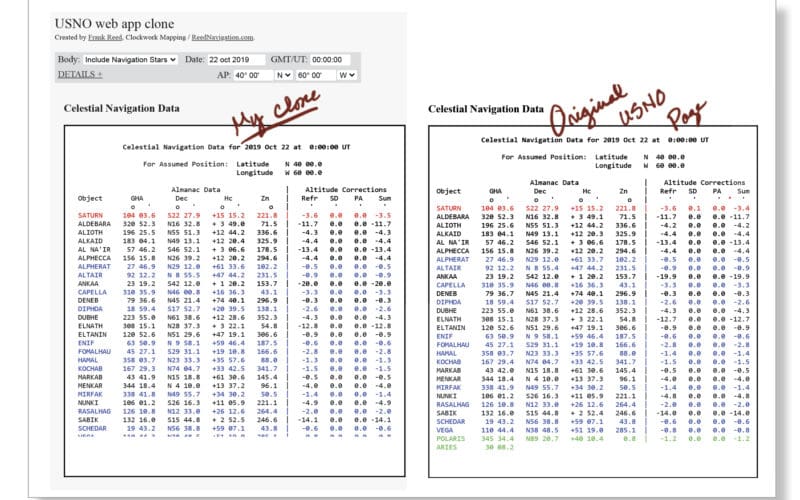

In the past year, the U.S. Naval Observatory (USNO), the primary source for the Nautical Almanac in the U.S., took down the online version of the almanac as part of an effort to modernize the USNO website. The online almanac was supposed to be back up by April of this year, but as of this writing in mid-September, it is still offline. One enterprising celestial navigation expert, Frank Reed (with a celestial navigation website of his own at ReedNavigation.com), took it upon himself to bring back the USNO by “cloning” it.

The Nautical Almanac includes the daily positions for the sun, moon, navigational planets, and navigational stars (these positions are collectively called ephemerides) for an entire year.

The USNO has been compiling the ephemerides of the Nautical Almanac since 1852 and publishing it in book form. When the Internet Age dawned, the USNO began offering the online almanac, and has done so for years. The online almanac was described by Reed in an email as an “antique, ‘celestial navigation data’ web app … Those of us who examined their web app determined long ago that it was a simple text-based wrapper for data generated from a legacy app (originally a DOS app) called MICA.”

Reed’s website has had its own astronomical ephemerides calculation apps for many years and he knew that to generate a version of the USNO online almanac would not be difficult based on what he had previously built for his site. “I have had the necessary back-end app that processes ephemeris data and calculates the positions of sun, moon, planets, and stars in various coordinate systems useful to celestial navigation since 2004. I originally produced these tools to analyze lunars so they are designed to be accurate to one second of arc. The original ephemeris data comes from the same ‘best in show’ source employed by the editors of the government-issue Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Almanac, too, namely the JPL numerical integrations of the Solar System and the Hipparcos star catalog.”

Equipped with this essential background, Reed was able to reconstruct the USNO version. “I have never used MICA, but its output is straightforward to generate. All I had to do to clone their app was to create a new backend or ‘server-side’ almanac. Since my other apps — such as my online ‘nautical almanac’ app — already calculate GHA, Dec, Hc, and Zn for the standard celestial objects in celestial navigation, it was easy to create a new web app that would reproduce the general appearance of their ‘missing-in-action’ web app.”

While most of us are happy just observing and reducing a single sun sight, other celestial navigators, like Reed, are made of sterner stuff. He found the process of cloning the site fairly straightforward. “Was it hard to clone? Not at all, given that my other apps already existed. I spontaneously announced my plan to create this clone during my online ‘Office Hours’ (open to the public, link is on my website) on Sunday, Sep.13, at 2:00 p.m. I started in on it at 5:00 p.m., and the app was done and running by 5:00 a.m. after a marathon coding session … I don’t calculate the positions of the celestial bodies. Most developers of apps like these spend months fine-tuning code that works out the positions of the planets and the moon and so on with complicated algorithms involving hundreds of mathematical terms. There are vast collections of tools for this amounting to many megabytes of code. Apps built that way, running on thousands of devices all around the globe, are re-calculating the same quantities millions of times over, which have already been worked out to exacting precision by the primary source at [NASA’s] Jet Propulsion Lab. We know ‘exactly’ where the moon is going to be on July 7, 2033, for example! We don’t need to re-calculate it. Instead, my apps use a simple table lookup, just like a traditional paper almanac but in code. The app has within it the daily (and when necessary, hourly) positions of all the celestial bodies. There’s no computation except for simple interpolation between tabulated values. This is much easier in terms of code and also much safer since there are far fewer possibilities for bugs.”

Maybe the biggest question you can ask is why someone would go to this extent to reproduce an online almanac that is a bit old-fashioned, and for which there are a variety of substitutes. Reed had a colorful answer, “So why clone the Naval Observatory’s antique app? It’s not that valuable, and there are other tools, including some of mine, that already fulfilled its role. First, I miss it! There were days when I would find myself thinking, ‘I just want that USNO app.’ But the real answer is occult magic. As I said to a number of people, given Murphy’s Law and such, I half expected the USNO website to re-appear the day after I launched this clone. And I do count my ‘clone’ as a little magic spell to get their site back up and running.”

Reed’s site “clone” is still filling in for the USNO web app, and you can access it here: clockwk.com/apps/USNOclone/. Check out Reed’s excellent lunar distance calculators on his site — we talk about lunar distance measurements in this issue’s celestial navigation installment.