When I departed Long Island, N.Y., on July 5, 2013, I was making my fourth attempt to cruise Antarctica aboard Fiona, my well-traveled Westsail 42. My plan was ambitious: a westward-bound circumnavigation of the Antarctic continent.

I had successfully made it to Antarctica twice. On my one previous unsuccessful attempt I suffered a broken rib due to a knock-down just north of the Falkland Islands.

This Antarctic circumnavigation cruise did not start auspiciously: one crewmember did not show up in time for departure. I double-handed across the Atlantic from Long Island with the remaining crew, Wade. As we neared the Canaries, Wade learned his son was seriously ill and flew home from Tenerife. It was important that I stick to a schedule as the window for the Antarctic leg was only about eight weeks long, so I single-handed across the Atlantic to meet a cruising couple, John and Helena in Brazil who sailed with me as far as Santos. There I met David who had signed up for the Antarctic leg. We double-handed to Punta del Este, Uruguay, to pick up the remaining crew for the Antarctic, Simon and Bob. We refueled and loaded on tons of food before leaving for Port Stanley in the Falklands. There we prepared the boat for a crossing of the Scotia Sea: we installed deadlights on the main cabin windows, wooden cover on the aft hatch, double lashings on the rigid dinghy on the foredeck and we shipped a 65-pound fisherman’s anchor.

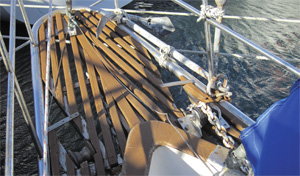

|

|

A 65-pound fisherman anchor was lashed to the bow pulpit for use in Antarctica. |

The forecast for the day we left was 30 knots from the west, which was okay as this would give us a beam reach. Our destination was King George Island in the South Shetland Islands, which lay almost due south of the Falklands. We left with the storm mainsail bent on, this is smaller than the working mainsail and has two reefs, the second being very deep, leaving almost a trysail when set. In Port William Sound before we encountered the offshore wind we tied in the first reef.

Pegging the wind needle

Offshore the wind was blowing hard with gusts to 50 knots, so we furled the jib and sailed with the reefed main and staysail. We tied the second reef in the mainsail. It was good timing; I watched with amazement and some trepidation as the anemometer climbed above 60 knots, the needle vibrating madly on the end-peg. That night we plowed south with shortened rig in rising seas. As the gloomy scene lightened with sunrise the wind dropped into the 30-knot range. The boat was taking a battering from huge waves. We shook out the second reef with foredeck gang wearing harnesses. The sea conditions were very rough.

I had just retired to my bunk in the aft cabin for a post lunch nap when Simon called out that the forward bilge pump wasn’t working and the head was flooding. I worked my way forward. There was a lot more water than just a stuck pump would account for. Even as we watched, the water level rose rapidly — we were sinking by the bow. By the time we had assembled a couple of pumps, the water was over the cabin sole. We got a bucket brigade going and I went into the water, sloshing around in the forward head to find the leak. A stream of water was running down the inside of the hull on the port side from somewhere behind a locker. The only thing up there, out of sight, was the gooseneck for the head, I shut the main thru-hull valve for the toilet and the stream slowed considerably.

|

|

After departing Port Stanley, Forsyth and crew encountered heavy weather leading to a series of gear failures. At 53° S, 59° W, Forsyth made the decision to turn away from Antarctica and head for Cape Town. |

|

Alfred Wood/Ocean Navigator illustration |

When we got the water down to a manageable level I peered behind the panel in front of the gooseneck, the hose from the thru-hull valve was detached from the plastic “U,” almost certainly caused by excessive pressure as the huge waves slammed into the bow. Water had been pouring into the boat through an inch and a half hose open to the sea, I figure we were minutes away from sinking, or, at least, shipping enough water to cause a capsize. The problem in reassembling the gooseneck was that the white sanitary hose used in marine toilets hardens like steel when it is cold. To get the thing back together, David and I had to put the ends of the hose in boiling water to soften the plastic so it would slide over the barbs on the thru-hull valve and the U-fitting. Working in the pitching bow with sea water and the contents of the discharge hose sloshing about was tough and for the first time in more than 30 years was I seasick. Later we found the forward bilge pump was completely clogged by debris, which always happens when the water rises to new levels.

Interior soaked

The interior of the boat was saturated; besides the water splashing about from what was left in the bilge, the pounding seas found every crack in the caulking and forced water in. On the starboard side of the main cabin the pressure of the waves thudding on the sides forced the rubber gasket out from between the movable port and its frame. The result was that water gushed onto Simon’s bunk every time we hit a wave. All the other bunks were also soaked. As evening fell on the second day we retied the second reef in the mainsail in a wind that gusted to 45 knots. The wind slowly veered to the southwest and Fiona began to sail east of the rhumb line as she slogged to the south. After a few hours we gybed onto port tack and headed west, this produced a whole new set of leaks as the waves crashed against the port side. The navigation table was flooded and my laptop computer went the way of all flesh. Also, the inverter in the engine room failed along with many other victims of the flood. Two five-gallon jerry jugs filled with diesel disappeared from the aft deck.

|

|

To prepare for the expected heavy boarding seas of the Southern Ocean, the crew installed deadlights on the main cabin windows to protect them from breaking. |

In due course I decided we had sailed far enough to the west and asked Simon, who was on watch at the time, to gybe onto starboard tack. When Simon grabbed the wheel, which had been locked to the wind vane, he found it spun freely; the steering chain was broken! It is testimony to Fiona’s sailing ability that for some time she had been holding a good course in tremendous seas and strong winds without any rudder control.

A quick look under the pedestal revealed the failure; the master link fastening the chain which passes over the wheel sprocket to the wire rope leading to the quadrant had snapped under the tension needed to swing the rudder in the heavy seas we were enduring. Fitting a new master link took only a few moments and I noted in passing that there was only one other master link left in the spares kit. The problem was that the wire rope leading to the quadrant had come off the sheaves and the grooves in the quadrant, which was swinging violently as the rudder oscillated in the heavy seas. Getting the wire back was not going to be easy; the quadrant, which is a heavy bronze casting, fitted neatly in the quadrant box with little room to spare. With Bob helping, I lashed the quadrant to the end stop with rope and slipped my fingers between the quadrant and the sides of the box to get the wire back in the grooves. If the quadrant slipped its moorings to the stop I was going to be short a few digits. Bob guided the rope into sheaves under the aft cabin sole at the same time. Eventually we got everything in place and tightened up.

Appearing out of the gloom

As we went on deck to try the wheel, Simon gasped and pointed ahead; looming out of the gloom and spray were the rocky cliffs of lonely Beauchene Island only a couple of miles ahead, the most southerly outpost of the Falkland archipelago. We had got the steering fixed just in time to gybe over and head southeast again. The wind was 40 to 50 knots with occasional gusts that hit 60 knots.

|

|

Fiona’s rudder quadrant with tight clearances to the surrounding box. |

A few minutes later I was below when I heard violent sail flogging and Bob poked his head through the companionway hatch to say the staysail boom had broken! I rushed on deck to view a scene of devastation on the foredeck: shreds of Dacron lashed by the wind flew from the forestay and a port shroud. Bob and Simon struggled to get the staysail halyard down; the sail had split in half. When we got things a little more under control, it was possible to figure out what had happened; the swivel on the staysail outhaul block had sheared and the adjacent cleat had been wrenched out of the staysail boom. With this mess attached to the staysail clew, the sail had rapidly flogged itself to destruction. Although the boom had fallen to the deck it was not actually broken. I now faced a difficult situation; although I carried spares for the jib and mainsail, I did not have a second staysail. Without the staysail Fiona’s ability to sail to windward — particularly in winds of more than 25 to 30 knots when we weren’t using the jib — was seriously compromised. Most of the other failures already mentioned could be dealt with and Antarctica was still within reach, but the loss of the staysail forced a reappraisal of the cruise objectives. I knew there was nowhere nearby that could provide another sail. Probably Santos in Brazil was the best bet, but if we sailed to Santos there would be no time to head south again in the 2013/14 season, so Antarctica was out.

I was bitterly disappointed. The cruise had been in preparation for nearly a year, and, of course, David, Simon and Bob had signed up specifically to visit the Antarctic continent. Standing in the heaving cockpit with the spray flying in the howling wind, my heart was heavy; it looked like this was as close as we were going to get to Antarctica. I told the crew that I thought we had done our best, we had been very unlucky to run into weather like this and we had to consider how to get ourselves home in one piece. I felt our best strategy was to head to Cape Town, all the facilities were there that we needed — it was a long way, but it was downwind!

Turning away

Accordingly, at 53° south and 59° west we turned the boat around and headed northeast. Sometimes turning around when the destination is so close is the hardest decision one can make. The trip to Cape Town would be no picnic; it was about 3,500 nautical miles away, mostly sailed in the Furious Fifties and Roaring Forties. As it turned out, the decision was the smartest thing I could have done; we later discovered the main water tank had shifted in the melee and cracked; half the fresh water had leaked out. Later I compared notes with a crewmember of a cruise ship navigating the same area; he said they were hove-to with a wind of 75 knots.

|

|

Broken chainlink from Fiona’s steering system. |

During the next couple of days we rolled downwind, cleaned up the boat and tried to dry out our clothing and bedding. David rescued the hard drive from my flooded computer and pronounced the data could be retrieved. He managed to transfer the program used for SailMail to his own laptop so we again had limited e-mail capability, a major feat in the soggy, bouncing boat. One of the first e-mail messages I received was that the Antarctic pack ice was the farthest north it had been for 34 years, confirming that even if we had made it to the peninsula my original plan of an Antarctic circumnavigation would not have been feasible. The wind was variable and at times fell to 10 knots, but mostly the log mentions relative winds of 20 knots with swells rolling past the stern. I decided we would visit Tristan da Cunha Island, it was almost on the direct path to Cape Town. I had sailed there once before, 12 years earlier. I felt the crew would enjoy the chance to visit this isolated community. It was a leg of 2,000 nautical miles.

Second steering failure

Four days later, after enjoying typical 50s sailing, that is, frequent swells washing into the cockpit, what I dreaded occurred: the steering failed again. Fortunately the wind was in the 15-knot range and we hove-to under the reefed mainsail. On inspection I again found that wire rope was dangling from the quadrant and at first I just assumed the wire had stretched and dropped out of the grooves.

In order to keep the quadrant from shifting, we rigged the emergency tiller to the rudder post extension and Simon sat on deck holding the tiller over. Although the wind was not strong there was a heavy sea running and he had to work hard to hold the rudder in position. As Bob and I toiled in the aft cabin the boat rolled quite violently. Suddenly there was a bang like a gunshot and the quadrant crashed to the other side, fortunately our fingers were not in the way.

Simon was still holding the tiller in the original position; the substantial cast iron universal joint between the rudder post and the extension had fractured, this entirely due to the force of a wave hitting the rudder. As we had done on the previous failure, Bob and I tied the quadrant down with rope and finished repositioning the wire rope. When this was done it was obvious that the problem was not the wire stretching; something was broken. By this time we were all exhausted, the motion of the boat was fatiguing, night had fallen so we let Fiona lie hove-to while we ate a simple supper and caught some sleep.

|

|

The torn staysail stretched out on the dock at Cape Town. |

I lay in my bunk with dark thoughts; without the emergency tiller there was no way of steering the boat if we could not fix the original system. We were hundreds of miles from the nearest land — South Georgia Island — which was hardly a haven. I had no idea how we would steer if we could not fix the failure.

In the morning I discovered that the chain had broken inside the steering wheel pedestal; to get at it, the compass and engine controls had to be removed. We all gathered in the cockpit and carefully stored each part as I removed them so that they would not get lost in the pitching, rolling boat. We fished out the chain from the sprocket attached to the wheel and I removed the broken link using a grinder on the universally versatile Dremel tool. I inserted the last master link in the spares kit to join the chain together.

This was the last major failure, although I felt the sword of Damocles was hanging over us each time I saw the wheel working hard. Running down the 40s we had the usual minor problems; chafe of the Aries lines, whisker pole topping lift breaking, etc., but basically the boat held together and as we worked to the ENE the weather moderated and it got perceptively warmer.

Tristan da Cunha

Three weeks after leaving Port Stanley, the misty outline of Tristan da Cunha came into view. We had sailed about 2,500 nautical miles. There is a settlement on the north coast called Edinburgh, where a few hundred souls scratch a living by fishing. When we arrived the wind was quite light and we anchored, with some difficulty caused by thick beds of kelp, a few hundred yards off the shore. Being an open roadstead with no lee, it was rolly. The person on the marine radio told us we could not land as the place was shut down for a public holiday.

|

|

Eric Forsyth aboard Fiona following arrival in South Africa. |

The next day Simon, David and Bob dinghied over to the jetty while I stood by on Fiona. The harbor master assessed the conditions at the jetty and waved them away. So they returned to the boat, we put the inflatable away and upped anchor in a rising wind. Simon, on the bow, had to pull masses of kelp off the chain as it came up. We bore away for Cape Town, 1,500 miles to the east.

The weather north of 40° south was pleasant and we enjoyed wonderful sailing with favorable winds. Six days after leaving Tristan it was Christmas; out came our traditional tree and to no one’s surprise Santa Claus managed to leave us a few small presents. Cape Town was not far away and early on the morning of Jan. 2, 2014, the distinctive outline of Table Mountain welcomed us to South Africa. We had sailed 4,090 nautical miles from Port Stanley.

The weather after we left the Falklands was atrocious, and bore little resemblance to the forecast. It wasn’t the worst weather I have ever been in, but close. I felt particularly chagrined that I had exposed the crew to this rough treatment by Mother Nature when nothing in their previous sailing had prepared them for it. But they bore up wonderfully; David, Bob and Simon were great crew. As for myself, it is almost impossible to express the disappointment I felt when I made the prudent decision to turn away from Antarctica. When we swung Fiona’s heading to the northeast on that stormy night, I knew I might never get that way again, which some might consider a blessing. But for me it seemed like the end of a chapter of my cruising life.

————

Contributing editor Eric Forsyth has sailed his Westsail 42 Fiona nearly 250,000 miles, including two circumnavigations. He is a past winner of the CCA’s Blue Water Medal.