Editor’s Note: New Zealand voyager Peter Smith lives and voyages aboard his 52-foot custom sloop Kiwi Roa. This account is written by his son and sometimes voyaging companion, Craig Smith.

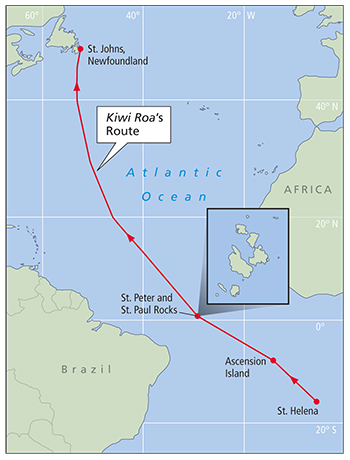

Kiwi Roa had spent some time in Southern Africa, cruising from Cape Town up the Skeleton Coast to Namibia. After having spent the prior years based in Patagonia and exploring the Antarctic Peninsula and South Georgia Island, Peter’s medium-term goal was to head back to the high latitudes. To accomplish this, he had been contemplating a long diagonal passage across and up the Atlantic, all the way from Walvis Bay to the northern Atlantic and Canada. The isolated Atlantic islands Saint Helena and then Ascension Island are on this route. Their location on this main route across the South Atlantic has lent them strategic value since about the time of Sir Francis Drake. We stopped briefly at Saint Helena, but in the scheme of things it was a mere interlude in what was to be a 6,500-nautical-mile voyage.

Saint Helena is about 1,200 miles slightly north of west from Walvis Bay Namibia. This angle is preferable to the alternative of departing from a point farther south, as it rotates the trade winds away from the stern onto the port aft quarter. Running flat downwind can be tiring and hard on gear and sails. The more northern start gave us a fast reach all the way out, Kiwi Roa feeling more like an express train on rails than the sluggish expedition yacht that is more common in lighter and less favorable conditions. In the space of a few days, Africa was a fading memory and we were back in the middle of the South Atlantic.

|

|

Peter Smith’s Kiwi Roa on a voyage in Patagonia. |

Ascension Island is some 800 miles northwest of Saint Helena, of which it is a dependency. The administration does not encourage tourism, although a permit with strict requirements can be acquired in Jamestown for a fee. There are, however, severe restrictions on movement around the island. A number of different countries requiring the ultimate in security have set up a presence, and historically it has been a strategic mid-Atlantic base of great value — particularly during World War II and the Falklands Conflict. The RAF still have a station here, and other organizations to set up shop include the European Space Agency with a spacecraft tracking station, NASA with a telescope monitoring orbital debris, British and American signals intelligence facilities and even the good old BBC.

Vessels heading for Canada, Bermuda, the Azores Islands or around the Azores High to Europe will find Ascension is very close to the recommended route. The island does see a number of vessels every southern winter that are prepared to negotiate the permit requirements. Kiwi Roa was heading for Newfoundland and Ascension has no provision for landing a small dinghy, so we decided to satisfy ourselves with just getting a close look at the island.

Green Mountain in the distance

After a quiet and slow-paced downhill slide under poled headsails and in the light of a full moon, Ascension’s southeast head was raised in the early morning hours. We sailed the remaining miles along the northwestern coast under main only, taking in the ever-changing coastal rock inflamed by the dawn sun while the central backdrop of Green Mountain loomed in the distance.

With only a small human presence in the middle of nowhere, the sea and bird life is prolific. The wide variety of bird life includes frigatebirds, white and sooty terns, tropicbirds, boobies, gannets, skuas, various petrels and the brown and black noddy — and all were in evidence.

|

|

Kiwi Roa’s route took it across multiple bands of global weather, including the ITCZ. |

As we got closer to Georgetown, the central administration area, a bewildering array of man-made trees, steel structures, masts of various sizes and heights, and arrays of wires and cables came into view. White buildings, parabolic dishes and domes of varying sizes stretched along the coast.

Finally, the Clarence Bay anchorage came into view, marked by the appearance of two other sailboats at anchor disappearing periodically behind the unbroken Atlantic swell. Anchored well out was a large freighter with a British ensign flying. Our Rocna anchor was going to earn its stripes.

We found a spot between a large floating hose siphoning petroleum products from tanker to shore and an extensive shoal that projected out from the shore and dampened the swell. Anchoring in conditions like these requires finding deeper water, 30 feet or more, and using plenty of scope to allow for the surge. A good long spring line is needed to absorb shock and protect the anchor chain as it goes taut on the uplift. This can surge 25 tons of boat with enough snatching force to stretch chain and damage deck bollards, not to mention unbalance a cup of coffee. As we have come to expect, the Rocna did not budge.

|

|

A supply boat visits the mid-Atlantic Brazilian archipelago of St. Peter and Paul Islands. |

A small ferry launch was running out to the ship occasionally, and it picked up crew from one of the yachts. Watching the dangerous antics involved with the possibility of serious damage, we concluded that a shore visit to stretch one’s legs was not of the highest priority, and Kiwi Roa’s trans-Atlantic was recontinued the next day.

Returning to high latitudes

Our final destination was Newfoundland. The intent was to get back to the high latitudes and more adventures — this time northern rather than southern — and Peter didn’t want to dally with the regions in between as he had visited the Caribbean and Americas years earlier. So, the pilot charts were consulted and a route was laid out where the prevailing winds might cooperate: 4,500 nautical miles across the Atlantic.

White-tailed tropicbirds saw us off while Ascension receded astern. Winds were as expected: light to moderate southeasterly with flat seas. Kiwi Roa’s yankee and No. 1 genoa were set on twin poles, complemented with variations of a reefed main, and the wind vane tasked with steering.

As we settled into the daily passagemaking rhythm, the occasional ship would appear on the horizon. One deviated from her course to pass close by our stern. Talking over VHF, the captain turned out to be a keen sailor looking forward to voyaging in his own sailing vessel one day.

|

|

Kiwi Roa with its headsails poled out in the North Atlantic. |

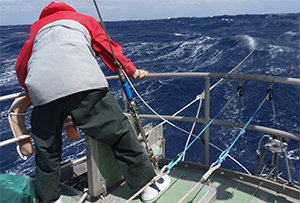

On approaching the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), the waters became productive for a daytime lure. We hooked a couple of mahi-mahi and horse mackerel, a rainbow runner and, to our distress, a sailfish. Peter abhors game fishing; these fight to the death, so it’s even worse to lose the fish once hooked — which we did — as it will almost certainly have died from its ordeal.

This prolific sea life produces a substantial seabird presence. We were visited by a variety of birds, including a migrating south polar skua familiar to us from the Antarctic. Brown noddies in particular found us a convenient overnight transport from one hunting ground to the next. Like fighters returning to their carrier, they would arrive around sunset to land, then in the falling darkness squawk and scrap among themselves over the ideal roost. Peter, annoyed with the prospect of harvesting guano from decks, would attack them with a boat hook. But the birds would not be discouraged. He eventually admitted defeat — and even looked forward to the company of these unpaying passengers.

Rafts of seaweed

Close to the equator, rafts of seaweed became a problem. At times, speed was compromised by as much as a full knot. We periodically had to stop, go head-to-wind and motor backward to clear the weed that had fouled around the prop, rudder and skeg. The autopilot had to take over from the wind vane since its servo blade regularly became fouled.

|

|

Generators and radio masts dot the island of Ascension, which is used as a listening post by British and U.S. intelligence agencies. |

Some eight days and 1,050 nautical miles from Ascension, we closed with the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago during the dark. We ghosted slowly in through the morning. These isolated mid-ocean rocks break the surface about 510 nm off the Brazilian coast. By claiming and occupying them, Brazil enlarges its marine economic zone manyfold.

They make for a slightly surreal setting: buildings on jagged rocks and a moored ship where by rights there should be nothing but ocean. A Brazilian trawler, apparently doubling as a support vessel, floated nearby, tethered by a warp to a buoy. In anything other than a flat calm there is no feasible landing, so stopping to visit the Brazilian naval station was not an option for us. Kiwi Roa continued on.

The doldrums of the ITCZ proved relatively benign compared to previous experience. We had to drop the sails on occasion to protect them, as steerageway was lost in the incessant roll. The usual thunderheads formed and threatened but no severe squalls followed through. Constant trimming and course changes for optimum wind saw us pick up the southeast trades in less than three days.

|

|

A variety of birds decided to hitch a ride north. |

Playing the Azores High

Once through the ITCZ, our course was determined by inspecting the most recent pilot charts and comparing these with daily grib files downloaded via HF. The prevailing winds of the Azores High circle the middle North Atlantic, shaping our route for an optimum sailing angle with the apparent wind always just forward of the beam. Peter laid out a series of waypoints at 10-degree intervals; the next waypoint on the route was adjusted periodically on inspecting each day’s grib file, with the general policy being to stay as close as possible to the basic rhumb line. This strategy worked well until we ran into the horse latitude’s variables unusually early at around 23° N. This brought a freight train of low-pressure systems across our northerly route, with ever-changing wind directions and strengths. The remaining 1,500 nm of fluctuating conditions and accompanying sail changes were to prove taxing.

A big depression we could not escape rolled over us around 40° N, 53° W. This system would stall, track south, stall again, then finally track back northeast toward Greenland — with Kiwi Roa on its western side for this whole sequence, giving us gale-force northerlies for four days. Rather than heave-to, which he does not consider a proper storm tactic, Peter decided to deploy the Jordan Series drogue early to minimize the loss of hard-won northing.

The drogue worked well as we only lost 40 nm in the two days the boat ran on it. Several lessons were hammered home about the forces of 30-foot breaking seas — which damaged the transom-mounted Monitor wind vane — and about recovering the drogue while the leftover swells were still 15 to 20 feet. This was concurrent, sadly we later discovered, with the capsizing of the British yacht Cheeki Rafiki and the loss of its four crew within only a few hundred miles of Kiwi Roa.

|

|

Deploying the Jordan Series drogue during rough weather in the North Atlantic. |

Pushing ever north with the North American coastline leaning in on us, the final four days of the passage were spent at 5 to 8 knots crossing the Grand Banks in unremitting fog so dense it was raining. With only radar for vision, landfall was heralded by the sound of powerful directional foghorns from navigation markers, lighthouses and ships.

As we approached St. John’s, our chosen landing for Newfoundland, the fog receded seaward and a Canadian Coast Guard ship towing a disabled trawler loomed out of nowhere on our aft quarter. A strange Newfie accent identifying itself as Harbour Control ordered Kiwi Roa into a queue of traffic entering and exiting the narrow entrance, and the trans-Atlantic was complete.

Peter Smith is a New Zealand boatbuilder, long-distance cruiser and offshore sailor, and designer of the Rocna anchor. He lives on board custom-designed, self-built Kiwi Roa, his 52-foot aluminum expedition yacht. In recent years, he has been ranging about the globe from Patagonia to Southern Africa and now back toward the high latitudes, this time in the Northern Hemisphere. Read more about Peter and Kiwi Roa, including more photos from other adventures, at www.petersmith.net.nz. Craig Smith is Peter’s son (and biographer) who was brought up in the cruising lifestyle. He now lives in Auckland, New Zealand, while trying to keep track of Kiwi Roa’s roaming.