Editor's note: New Zealand sailor Graeme Kendall sailed 28,000 miles solo around the globe aboard the purpose-built Astral Express, a 41-foot sloop. This circumnavigation included a 12-day transit of the Northwest Passage, reportedly the fastest trip through that waterway ever accomplished. This story is an excerpt from Kendall’s new book on his exploits, To the Ice and Beyond. In this excerpt, Kendall is in the North Atlantic with the Northwest Passage segment of his journey still ahead. Note that Kendall uses the Pacific term cyclone for storms that are called hurricanes in the Atlantic.

By this stage, Cyclone Harvey had already caused havoc through the Caribbean and then barrelled up the East Coast of the United States, swamping New York. I listened on the news, but I didn’t have access to the weather maps and couldn’t see exactly where he’d got to now. I was confident I was sailing away from it.

Stan and my shore advisors told me I should consider slowing down to be sure of letting it pass in front of me — but that went against everything that I had done so far, trying to push hard to be on time further north. I figured I’d be well out of Harvey’s way. These hurricanes didn’t usually come as far north as I now was.

And I was making great progress. Wind was freshening from the southwest and I’d had a blustery night sailing at 8–10 knots, peaking at 17.5 knots, with two reefs in the main. By morning, the skies were dark and the tailwind that I had been running with started to ease off. It dropped right away by about 8 a.m., so I decided to shake the reef out and go with the full main.

Massive gust

I was up by the mast and had just hoisted the sail to the top when I saw, in the opposite direction, water lifting off the sea surface in a pattern that was heading my way fast. I had just enough time to lower the mainsail and tie it to the boom when — WHAM — I was hit by a hurricane-force wind of between 75 and 85 knots. I had sailed into the centre of Hurricane Harvey. Here he was, further north than I’d believed him to be, at 40° 05’ W, 43°04’ N.

I was so lucky it hadn’t arrived a minute or two earlier. If I hadn’t been able to instantly get the sail down, Harvey would have blown it right out. The boat sat with no sail up as the storm went through.

I hadn’t been able to see exactly where the storm was. It could have been 40 miles to one side or the other and I might have been on the edge of the eye and just had strong winds all the time. In saying that, the eye of the storm is an area of no wind at all as the cyclone turns around it, and the wind direction changes depending on where you are across that eye. When you go through a storm like that, it’s got an area on one side that’s quite wide. It could be 100 miles wide, but on the other side is a narrow band but with stronger wind — perhaps five times the velocity as on the other side — and that’s what I sailed into.

It was off the scale. At its strongest I guessed 85–90 knots, which is more than 100 miles an hour, or around 170 kilometres an hour. It could have been 10 on either side. It was blowing so hard I couldn’t stand up without holding on. I just held on. Mostly I was inside the boat or hatchway. If I was on deck, I held on or crawled.

|

|

Kendall at Astral Express’ nav station. |

It lasted maybe six or seven hours, blowing so hard I knew it couldn’t blow for long. It was moving on, and I just had to hold on.

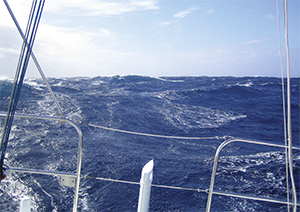

In conditions like that, the sea is blown around so much that it feels as if it’s raining all the time. Wave caps are white from being whipped around. The waves weren’t especially high to begin with, but the problem with the wind coming up so quickly was that the seas were close together. That was the danger. If they rose big and close, that’s when you got into trouble. I knew that if I got two together I could roll.

I wasn’t scared but I was concerned. I had plans to follow, and that kept me logical and methodical. My rule for situations like this is to stay with what you’ve got. You’ve prepared something so stay with it, trust it. Trust the boat, trust the design, trust the skill that’s gone into building it. Trust the equipment. Trust all the planning that has got you to this point.

Fear comes when you’re out of control. I was in a dangerous situation but I was in control. I had options. I had plans and I moved through them.

Plan A was to lay ahull with the wind and seas coming from the port side. This is one way of weathering a storm, by downing all sail, locking the tiller to leeward and going with the storm. But it was such an incredible wind that this quickly proved impossible. The seas were starting to rise, and I knew if it went on like that she would roll.

Plan B: I tried running off, but even without any sail up the yacht was moving too fast and would pitch pole. I went back to laying ahull, which meant letting the boat drift sideways at about 1.5 knots with the wheel locked hard over and the seas just washing underneath. But as time went on the sea got bigger, and if it got too much bigger there was a chance it could have turned me right over. That’s what I was preparing for.

I stood in the doorway, wet-weather gear on, ready to close the watertight door if she rolled.

It was definitely scary with the wind screaming around me, but my knees were not knocking. I was as prepared as I could be with everything inside tied down that I could manage, although if there’s a rollover you get a hell of a mess. It would roll over and it would come back up. Chances are the mast could break if it rolled over. I might lose rigging. But I thought that, if the boat had rolled, it would have rolled over quite well. Its keel was deep, it would have done the thing, but it would be silly to sit there and let it roll again. You’d have to do something to hold it into the wind, and that’s how I got to Plan C.

Plan C: I had a sea anchor that I’d bought in the local marine shop the day before I left Auckland. It was a large canvas cone like a small parachute that, when lowered into the water, acts like a brake and helps to hold the boat in a desired position. I tied a long rope to it and crawled up the deck to the bow. I had my harness on and a lifeline all the way forward.

|

|

Kendall’s route took him across the path of Hurricane Harvey. |

If I had just let the sea anchor go it would have flown like a kite in the 85-knot wind. So I bunched the thing up, lay flat on the deck, leant over the bow and threw it vigorously down into the water. It drifted away. I had the rope cleated to the bow and, when tight, the water filled the canvas cone and the bow started to come around and head into the wind. Perfect, I thought.

But then the ropes attached to the sea anchor broke loose and the grip was lost. I discarded it in frustration and crawled along the deck back to the relative safety of the cockpit.

The seas were getting dangerous. The waves seemed to be sliding underneath, but if two waves broke close to each other I was sure she would roll.

Plan D: The rope ladder used for going up the mast could be used as a drogue in the water, especially if looped. So this was my next move: to unpack it on the cockpit floor, take it to the bow and use it to try and do the same job as the sea anchor in order to hold the boat head-on to the wind and waves. I had my head down, unpacking the ladder as waves crashed against and over me, but I looked up for a minute and happened to glance to windward where I noticed a thin sliver of blue sky on the horizon. I knew instantly that this would be the end of the blow. I just needed to hold on.

The horizon was 12 miles away, so whatever speed Harvey was moving at I knew the end was in sight. But it seemed to take a long time.

Plan E, and I was not sure how many plans I had left. Even with no sails up, the mast and the rigging were enough for the wind to keep the boat heeled over.

Sometimes a storm will be so bad that a crew will actually take the rig off to survive. They’ll undo the rigging and drop the mast and let it go over the side, or chop it down and get rid of it. Without the mast up, you haven’t got that wind leverage pushing the boat over.

It wasn’t something I had got around to considering. I guess if the boat had rolled over and I couldn’t do anything but let it roll over again, I might have considered dropping the rigging. It would have been a huge loss, though, and it’s dangerous.

|

|

On a trip around the globe, big seas become second nature. |

It would have been very hard on Astral Express to drop the rigging. The mast goes through the deck into the base and it’s got ropes on it. You’d have to get the knife out and cut everything, get the bolt cutters out and chop the wire rigging off, and hope the mast would break cleanly. But there would be no guarantee of that. Then you’d need it all to just disappear cleanly over the side. It would be a real mess, and very difficult on my own.

If it had got to the stage where I thought “Forget the trip, forget keeping everything intact, it’s a matter of survival here,” I would probably have gone straight to Plan F.

I had, of course, been contemplating Plan F: escaping on the life raft. Getting the life raft out and inflated — it would not have been easy. To put it in the water and try and jump in would have been almost impossible. In this extreme wind, it would have behaved like a kite and taken off before I could even get it over the side. How would I manage it?

I figured I’d inflate it in the cockpit, keep it tied on and sit in it. Then if the boat rolled or sank, I could untie it and it would float off. That would be the only way to evacuate, with grab bag at hand. It’s called Plan F for a reason, because that’s the point where you’re f…

Then came a time when I knew in my bones the wind was dropping, although it seemed to take a long time. Ever so slowly it would ease off, only to come back again in force. But after some time, the sliver of blue sky got larger and the wind eased and I lived to tell the tale.

Little damage

The only damage I could find was that the sun and spray cover in the cockpit was a little torn, although it could be easily repaired with tape. And there were a few frayed nerves. An experience like that is physically exhausting, even though there was quite a bit of time when I wasn’t doing much. I had no sails up. I had the wheel tied over to one side on lock and I just had to stand there letting it happen, eating food that I didn’t have to cook or prepare such as biscuits or chocolate, and drinking water.

I was a bit disappointed I’d got into that situation by not holding back. Chances were that if I’d not kept going as fast I had, trying to beat Harvey, it would have just passed in front of me. I had been given advice to slow up, but I’d felt that with that tailwind I was going fast enough to sail through and would beat it. But then, while it turned out to be prudent advice that I should hold back, the people back home didn’t know exactly where the storm was, or where I was either.

My mistake came from not having a weather map on board at that particular time. But as the wind died away I mostly felt relief that it hadn’t lasted too long. I was glad it was over, and I was happy in the knowledge that the boat had passed its first real test. I knew now what it could stand. That was good knowledge to have once I was facing the Bering Sea because, although the seas would be bigger there, the wind would not be as strong and I now knew the boat was able to handle what was dished out there.

|

|

Astral Express used a transom-hung rudder to protect it from the ice of the Northwest Passage. |

I got everything tidied up. I put things away — life jackets and wet-weather gear, my grab bag which had been all ready to go. Re-packed the life raft, re-packed the ladder. I’d had everything tied down below so that if I rolled over things wouldn’t fly around, so I tidied all that up and got it back to normal. The sun came out and the boat dried out and we were back on the journey again.

As I came into the trade winds, I had squalls coming through every three or four hours. Like a thunderhead, the wind would increase suddenly about 5 to 10 knots, usually bringing rain. They didn’t last long though — if I decided to have a wash, by the time I’d lathered up it would be gone.

Of my two rainwater-collection systems, one took about 10 minutes to set up, which wasn’t suitable for a squall, and was difficult to manage in the wind anyway. But the other system worked well in these conditions. The dodger in the cockpit had a little hole in the middle of it with a screw cap in it so I could attach a hose from there straight into a water bottle. It was ready to go straight away, and a few minutes of heavy rain was enough to collect up to 10 litres of fresh water, which was enough to use for washing or topping up.

Squalls were just something I had to live with. They showed up well on the radar, so the radar alarm would go off when one was about eight miles away. I’d set the boat up, reduce sail or just steer the boat downwind a bit, alter course 10 or 15 degrees for 20 minutes and then get back on course.

I realise a lot of people would be freaked out at the idea of sailing through a storm of the magnitude of Cyclone Harvey. People have asked me how I handled it. I think it comes down to having an optimistic nature. If you had a pessimistic nature you wouldn’t do what I did. You wouldn’t untie the boat to begin with. Sure, I ask, what are the odds of something bad happening? What are the odds of dying? I temper my optimism with experience and planning and I trust my own processes and the skills of the team I’ve built up around me. Mental attitude has a big part to play.

Some people turn to God when they’re in extreme and dangerous circumstances. That’s not how it works for me. I think “God” is a word that expresses the limits of our understanding — it’s a word for the unknown. We’re taught where things come from; we know where that gadget comes from, how it was made. We know how we are made. But we can’t work out where the universe comes from. That “somewhere” is where the word God comes into use — so God is an unknown. The unknown.

Getting philosophical

When you’re out on the ocean alone, you do get philosophical. You see nature in all its extremes, and there you are in the middle of it all. When I was younger, I was so busy doing stuff, knocking myself around, thinking I was infallible. But as I get older I think it’s pretty amazing that we’re here at all. How does it all work? It’s just so incredible. Take the human body: for 60 years it’s been working, the knees, the heart, the hands. Never been for a service. Never been for an oil and grease. I give it sleep and food, but other than that it just keeps working. I guess I have a sense of wonder about it, and maybe that awareness becomes stronger as I get older. People say, what do you think the most amazing thing is, and I say, this: this hand. This ocean.

|

|

Ice steadily became a more common sight as Kendall headed north. |

I sailed right over the spot where Titanic went down in the North Atlantic at around 41 degrees latitude. There wasn’t a bump; no deckchairs floated on the surface. I looked around and all I could see was ocean — blue, blue ocean. No icebergs at this time of year, and a long way south for icebergs even in winter. The ship rests four kilometres down. I don’t think anyone ever calls their ship unsinkable now. I thought Astral Express was unsinkable — but I certainly never said it was.

At 15 weeks into my journey, Lancaster Sound was less than 2,000 miles away. I was making 150 miles a day, meaning I was 13.5 days away. It was now 11 August, so I thought I would make it on time.

I was in the Labrador Sea 350 miles from Newfoundland, sailing ENE to avoid two low-pressure systems ahead when I began receiving news that tropical storm Irene was approaching from the south. It had already drenched New York and was on its way to causing havoc in the United Kingdom. I hoped I was far enough north but I felt as if I was between a rock and a hard place. I needed to be at 57° N by Thursday, 18 August, but perhaps it wasn’t to be: On Friday, the NNW gale caught me. There I was in the centre of the Labrador Sea as the 45-knot gale set in. I had to run off and move south, then lay ahull again to slow the progress in the wrong direction.

I was getting close to Canada and starting to acknowledge that if this weather carried on I was not going to make it in time up to Lancaster Sound. I began to think about where I would go if I couldn’t make the Northwest Passage, and I figured the choice was between St. John’s at the eastern tip of Newfoundland or Nuuk, the capital of Greenland.

But then, thankfully, the storm moved off and I was able to get back on course. The chart shows where I went during Irene — it’s an almost perfect circle, out there in the middle of the Labrador Sea. That’s the thing with modern technology — everyone at home could see what I was doing. They got up and looked at their computers and saw where I was, and someone asked, “Why did you go around in circles?” I said, “I lost my hat!”

Goodbye Irene! By Saturday evening the gale was subsiding, and by Sunday the birds were back around the boat as usual. Time for a party — a shave and drinks.

I hadn’t used the engine since before Harvey, and the wind generator had been working overtime.

Water temperature was now nine degrees. Things were really cooling down and as I passed through 60° N on Monday, between Canada and the west coast of Greenland, I was on iceberg watch. I had seen no land since the Cape of Good Hope.

I was now approaching Davis Strait with Lancaster Sound about 600 miles away and Bellot Strait another 350 miles. Ice reports were saying that Bellot Strait and Peel Sound should be ice-free by the end of August. I had time to get there.

|

I spent a lot of time studying my charts of the area. I carried a full set of charts for the Northwest Passage from the Canadian Hydro Office. Although electronic charts for my course were supplied with the chartplotter, I felt it wise to have paper backup and found these necessary for studying the course ahead. Electronic charts had only just become available for the part of the Arctic I was about to sail through. I did have this advantage over previous explorers.

Graeme Kendall, from Christchurch, New Zealand, has owned several boats and sailed in the 1986 Whitbread Round the World Race and the 1987 two-handed Melbourne to Osaka Race. To the Ice And Beyond is available from Amazon and at www.iceandbeyond.com.