Voyaging is a healthy enterprise. The air at sea is unpolluted; the watch routine ensures that sailors spend more time outside than their landlocked friends; food can sometimes come fresh from the sea or, especially in the tropics, fresh from tree and vine. Regular, structured exercise, however, remains a problem. Lengthy passages mean days of living in a space only as large as your boat: walking a lap around the deck takes a minute or maybe two. Yet fitness is important for physical and mental well-being, and is particularly important for voyagers.

Exercise maintains and improves one’s physical condition. Strength exercises and stretching increase muscle mass; stretching also improves flexibility; agility training shortens reaction time and improves balance; and cardiovascular work strengthens the heart, lowering the resting heart rate and thus diminishing stress on it. Cardiovascular exercise has the added benefit of making you happy, the feeling known as “runner’s high.” Staying fit and maintaining a healthy weight for your height not only reduce stress on all vital organs, often prolonging life, but also ensure your capacity to engage in physically demanding activities.

This is especially necessary for voyaging. A good level of fitness increases your enjoyment and safety. It gives you the option of sailing in rougher seas and visiting remote locations, and it allows you to partake in more strenuous activities while ashore, such as hiking or scuba diving. On the other hand, poor physical condition makes voyaging close to unmanageable: if you lack the necessary flexibility and agility to climb aboard from your dinghy, you are limited to calling only at ports with marinas. If reefing the main takes more strength than you can muster, safety becomes an issue.

|

|

Seth reefs Heretic's main. |

The inevitability of rough weather makes fitness essential for your safety at sea. Although voyagers plan their routes according to favorable seasonal weather patterns, most sailors will eventually encounter storms that require physical strength and endurance. Autopilots and wind vanes can handle some gales but not all, and it is crucial to be prepared for heavy weather.

During our circumnavigation aboard our 38-foot cutter Heretic, my husband Seth and I encountered weather in all oceans. Much of it was short but violent rain squalls requiring hand-steering and expeditious reefing, but some was more severe. With very inconsiderate timing, our roller-furler broke just as a front off New Zealand struck us, so we had to man-handle our big genoa off the forestay while green water drenched the bow. By far the most exhausting, however, was a Force 11 storm we encountered while rounding Cape Agulhas, the southernmost point of Africa. After furling all sail except for a tiny blade staysail, we spent 16 hours at the helm to keep Heretic running before 30-foot seas. The force on the rudder demanded strong and quick reactions, and the sound of the wind and foaming crests taxed all our mental stamina. We weathered it successfully, however, because we had maintained a good standard of fitness throughout our voyage.

But how to do so? Fortunately, it is relatively simple. The motion of a yacht at sea ensures constant low-intensity exercise. Her rolling and pitching on the ocean swell keeps your body moving continuously; some muscle is always working to keep you standing, sitting, or even snug in your bunk against your lee cloth. My first long ocean crossing, the Pacific, surprised me in this regard. I was always hungry, and despite frequent hearty meals, I arrived in French Polynesia several pounds lighter than when I left the Galápagos. I couldn’t attribute my weight loss to the conversion of muscle into fat: I was slimmer, and I had no trouble hiking in the mountains of the Marquesas or hauling up our 60-pound CQR with our small, manual anchor windlass.

Our next two big crossings illustrated this phenomenon even more strikingly. Heretic hurtled across the South Indian Ocean before winds seldom less than 25 knots. The seas were steep and confused as the waves met a cross swell brewed in the Southern Ocean. Again I ate constantly and fell into my bunk exhausted at the end of my four-hour watches. The South Atlantic, however, served up a tranquil, almost calm, sea and a light but steady breeze. Instead of fatigue, Seth and I felt restless. Walking around the deck was insufficient: we started doing step-ups on the cockpit benches. This gave us our needed cardiovascular and leg work, although we had to take care to time our step-ups to Heretic’s roll.

Besides Heretic’s motion, I had her equipment to thank for my fitness. She had a hank-on staysail on her inner forestay, slab reefing for her main, and a big aluminum spinnaker pole. All her winches were manual, which meant that any sail change required exercise. Seth and I had to grind winches to trim the jib or stay, hoist a different headsail, reef the main, and haul up the centerboard when we reached port. At anchor (and even once at sea to clear a fouled spinnaker), I hoisted Seth up the mast to check the rigging, effect repairs, and photograph the panoramic view. Even everyday activities ensured minor physical outlay: pumping the head, pumping fresh water, and cleaning the cabin.

Fitness is even easier to improve while in port. Just as at sea, daily life affords much overlooked exercise. Weighing anchor with our small windlass always increased my heart rate and worked my arm and core muscles. Boat maintenance and chores sometimes require strength and stamina: sanding our wooden cabin trunk for varnishing, wrestling with a tight fuel filter to change it, or scrubbing laundry in a bucket. On both Heretic and our present 34-foot Herreshoff ketch Nahma, Seth and I have a rowing dinghy which ensures regular cardio and strength work. We often row “two-up,” each to an oar, so that we can both benefit. While the lack of an outboard motor is sometimes an inconvenience — to reach the town on Cocos (Keeling) atoll from our anchorage took an hour and a half of hard pulling — we enjoy the exercise and the quiet, which has allowed us to see birds (see The avian pleasures of voyaging), sea turtles, and even a dugong close up.

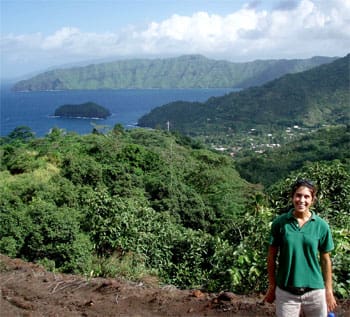

Life in port also affords opportunities for more conventional exercise: running, bicycling, hiking, and swimming. Since much of the joy of voyaging is exploring new places, Seth and I found ourselves getting exercise almost inadvertently. We climbed up steep mountain tracks in the lush tropical forests of the Marquesas and Fiji; we bicycled around New Zealand’s wine country; and we hiked along the windward cliffs of St. Helena and Antigua. In most of these places, such exercise is easily accessible. In New Zealand for example, a well-kept trail leads from the popular port of entry in the Bay of Islands, Opua, to its busier neighboring town of Paihia. The track weaves through tree fern forests, along a boardwalk through mangroves, and over one moderate ridge affording a view of the bay.

Even where such trails are not within walking distance, they can still be accessible. On Reunion, the French Indian Ocean island southeast of Mauritius, the bus system reaches almost all of its extensive trail network. A voyager moored at Reunion can hike for one day or twelve, looping among three giant calderas and even approaching an active volcano. Seth and I opted for a three-day trek between two calderas, climbing over steep passes and bathing in a waterfall.

Swimming, snorkeling, and even diving are obvious forms of exercise for voyagers while in port. Swimming laps around your anchored boat provides good exercise, but I found more fun in snorkeling above the coral reefs of Australia or among the penguins of the Galápagos. Seth and I kept two scuba tanks and dive kits aboard Heretic so we were often able to dive either from the yacht herself or from our dinghy. Thus we could swim over the wrecks of Bermuda and amid the kelp forests of South Africa.

While exercise is essential to prolonging your ability to sail offshore, it must correspond to your fitness level. Employing a rowing dinghy, a manual anchor windlass, and manual winches certainly keep you fit, but they must be manageable and safe. If you risk straining a muscle while weighing anchor by hand, an electric windlass will allow you to voyage more safely. Similarly, a well-placed electric winch could make big sails easier to handle. Partially because of these devices, some of our friends are able to continue voyaging into their 80s, and one man we met was even able to handle his boat alone despite missing his left arm.

As long as you are safely able to use manual equipment, however, your fitness benefits. Like Heretic, our current boat Nahma has slab reefing, a hank-on staysail, and manual winches. Yet voyaging provides a certain amount of exercise even if your boat had a complete hydraulic system. Between the motion of the yacht at sea and daily life ashore, one stays reasonably fit automatically, and exploring ashore ensures the best kind of exercise, that which is so pleasurable one hardly considers the effort.

————-

Ellen Massey Leonard completed a 32,000-mile westward circumnavigation via the Cape of Good Hope in 2010 at age 24. She and her husband Seth made the voyage aboard Heretic, their former 38-foot cutter. They now split their time between voyaging aboard their new-to-them 40-foot Francis Kinney-designed cutter Celeste and working in Switzerland, where Ellen is completing a book about their circumnavigation. On their next voyage they will attempt to transit the Northwest Passage through the Arctic. If successful, Ellen will be the youngest skipper to have done so and the second female captain ever.