In this issue we have a special section on sail technology, including a piece on how to keep your roller furling gear, both jib and main, in good working order. Roller furling, self-tailing, multispeed winches (some of them electric), rope clutches and more are all part of the sailhandling gear aboard a modern yacht.

Ocean Navigator, however, is also giving seminars aboard the new sail training vessel Oliver Hazard Perry, a 200-foot, full-rigged ship. Perry is a modern steel vessel in every way, except one: sailhandling. Like the other sail training vessels currently afloat, Perry will sail without a single winch — electric or manual — and no hint of mechanical roller furling.

On Oliver Hazard Perry, the idea is to learn to sail a tall ship the traditional way. The crew and the students provide the power to set sail, trim sail and douse (and furl) sail.

On a yacht, raising a Marconi-rigged main is essentially a single line operation: via the halyard. And a jib doesn’t usually even require raising — most voyaging boats have roller furling — you roll out the jib with a sheet.

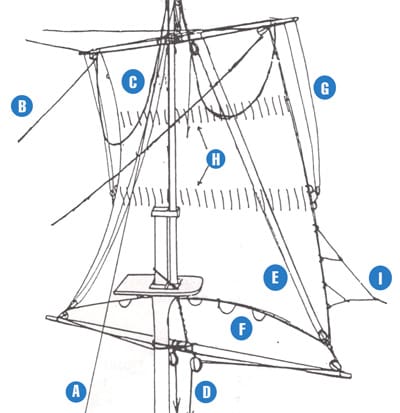

Square sails, however, are a bit more involved. Take the main topsail, for example. Like the sails on a Marconi-rigged boat, the main topsail also has a halyard. It doesn’t stop there, however. The sail also has two sheets, two braces, two clewlines, four buntlines and two reef tackles. All these lines must be manned as the sail is deployed and the yard raised.

More than anything, sailhandling on a square-rigged vessel requires teamwork. “It takes everyone on board to do it,” said Perry captain, Richard Bailey. As with anything, practice makes the process run more smoothly. A set of general rules also helps. Here are some rules that enable newcomers to become useful members of the sailhandling gang quickly:

1. Listen for orders — it’s essential that you always keep an ear open for the orders being given by the person in charge. When you hear an order, obey it promptly.

2. Do not give orders — the person running the sail evolution is the only person who can give orders.

3. Keep quiet — unless you have something relevant to say, such as “Port main topsail brace is manned,” or “There’s a fire in the forepeak.”

4. Only do things that you have been ordered to do — if you were not ordered to belay a line there is probably a reason, so don’t belay the line.

5. Make absolutely sure that you know which line you are supposed to grab — and make certain that you have in fact grabbed the line. If you are not certain, ask!

6. Have fun, but — bear in mind that this is serious stuff, so don’t have too much fun.

Setting and recovering sails is only part of the picture when it comes to sailing, of course. The other parts are trimming the sails and maneuvering the vessel.

Once they’re set, square sails are generally trimmed via the braces — lines attached to the ends of the square sail yards. The braces control the angle of the yard to the wind. Teamwork comes in here, too. Because the braces have integrated blocks, they have multipart purchase, making them powerful like a winch. The teams adjusting the braces need to act in concert. “If both sides are hauling,” Bailey said, “You could break a yard.” That fact points us back to rule No. 4: “Only do things that you have been ordered to do!”

Maneuvering a square-rigged sailing vessel is different from a fore-and-aft rigged sailboat in a number of ways, but one interesting difference stands out: On a Marconi or gaff-rigged boat, to change tacks the maneuver easiest on the gear and the crew is coming about or putting the bow through the wind. A gybe (putting the stern through the wind), on the other hand, carries with it the possibility of damaging the gooseneck fitting or the standing rigging or a member of the crew, should he or she get struck by the boom. A controlled gybe using the mainsheet or a device like the boom brake is needed to manage the downside of gybing.

On a square-rigged vessel, the preferred maneuvering technique is to put the stern through the wind — it’s called ‘wearing ship’ rather than gybing. Putting the bow through the wind is less favored. “That’s where the risk comes in,” said Bailey.

The reason for this difference is tied to the standing rigging of a square-rigged vessel. The forward half of a square-rigged mast must be free of shrouds so the sails can fly unencumbered. Thus, the shrouds are rigged to steady the masts from astern. When the bow is put through the wind, the foremast is the most vulnerable as it is only supported by the four forestays (the forestay, the inner fore topmast stay, the outer fore topmast stay and the fore t’gallant stay). So, in addition to the danger any sailing vessel faces of not getting the bow around and getting stuck in irons, for a square-rigger there is also the rare possibility of “knocking down the foremast,” as Bailey puts it.

These are just some of the fascinating wrinkles of sailing a square-rigged vessel. You can learn a great deal more on one of Ocean Navigator’s week-long sailing adventures aboard Oliver Hazard Perry this fall. It’ll be a great opportunity to get some hands-on experience working the sails on a square-rigged ship. And you can learn celestial navigation or marine weather on the trip, too. Check out the ON website or call Tim Queeney at (207) 822-4350 ext. 211 for more information.