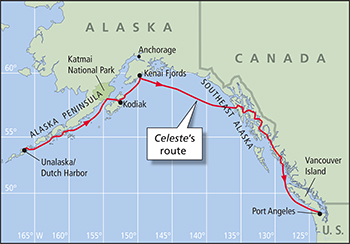

No one likes sailing to a schedule. It’s stressful; you never know if the weather will cooperate, or for that matter if the boat will cooperate. Schedules are much better as guidelines — plans written in sand at low water, as the joke goes. But sometimes they’re unavoidable, and this summer that was the case for Seth and me. We had to be back at work on Aug. 22, but we didn’t want to leave Celeste in the Aleutian Islands for another winter, so we had to reach our boatyard in Port Angeles, Wash., by Aug. 19 when our flight left Seattle. That gave us two months to cover 2,500 nautical miles of rather fickle seas.

To complicate matters, a typhoon from Japan had hit Dutch Harbor — the famous “Deadliest Catch” crab-fishing port in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands — during our absence last winter and had damaged our cold-molded wooden cutter Celeste. There’s no storage on the hard there, which is probably a blessing; considering the number of roofs that blew off houses in the storm, it’s possible Celeste could have been blown right off her jack stands had she been out of the water. Instead, she had heeled over so far that her port rail got caught under the dock. Her toerail splintered; one of her chain plates was bent; a turnbuckle got mashed, as did a Norseman fitting; several stanchions were bent at strange angles; and the genoa cars were pulverized. Knowing how badly the town had been hurt, we weren’t complaining, but even to do the most basic repairs to get Celeste sailing again would cut into those short two months.

|

|

Sailing along the mountainous Alaska Peninsula. |

A harbor with resources

Fortunately Dutch Harbor is home to many resourceful people and within 24 hours of handing over our bent chain plate to a machinist, he’d fashioned a new one. Celeste still looked a bit like she’d been through the wars when we left Dutch, but we’d gotten her seaworthy in a week. We still had seven weeks to reach Port Angeles.

Despite having spent a full summer sailing to Dutch Harbor via the Inside Passage and Prince William Sound in 2014, there was (and still is) much of Alaska that Seth and I wanted to see. We had to balance this with making tracks, so we started thinking of our cruise as a “best of Alaska” voyage.

The first “best of” spot we aimed for was the Katmai National Park on the Alaska Peninsula. Katmai is home to many brown bears, drawn to rivers rich with salmon, and — since we’re wildlife nuts — the park was one of our favorite places on our outward voyage. This year we were too early in the season for the fishing bears (the salmon had yet to come in to spawn), but bears still roamed the beaches and meadows, eating plants and digging for clams. For the first time ever, two park rangers were living in a primitive cabin in the area. Whether this was due to the centennial of the Parks Service or to concerns over too-close encounters between people and wildlife we never quite learned, though we suspected it was the latter. The rangers were about our age and we quickly became friends, drinking beers on their porch or our deck, fishing, hiking, and just chatting. Although our new friends were quite circumspect, we did learn that part of their role was to find out exactly what the bear-viewing/photography tours, which come out from Kodiak later in the summer, were getting up to — specifically, whether they were operating in places they shouldn’t be.

|

Decision to visit Kodiak

On our outward voyage in 2014 we had missed Kodiak, opting instead to spend two weeks exploring the emerald-green coves and sapphire-blue glaciers of Prince William Sound. So this time we did the reverse, visiting Kodiak instead of the sound. After a few days in the town, we had some glorious sailing in the myriad bays and inlets around the island, spotting seals, otters (some with babies), puffins and auklets. The same pod of orcas visited us twice, and once almost bumped our bow as they came up to breathe. Both Seth and I felt we could have spent all summer on Kodiak; there were so many good hideaways and so much wildlife.

Time was pressing, however, and we still had lots of places on our “best of” list. The prudent course of action would have been to make a straight passage across the Gulf of Alaska from Kodiak to Sitka. Weather windows for the Gulf are few and far between after the beginning of August, and it was already mid-July. Such a passage would have been the most direct route, barring sailing straight to Washington, and it would have gained us lots of buffer time in case of contrary winds or equipment failure. But the Kenai Fjords had been at the top of my list ever since bad weather had forced us to skip them two years earlier. So instead of steering east upon leaving Kodiak, we headed north. Yes, it was an overnight passage in the wrong direction and completely out of our way. But between the breaching humpback whales and the craggy spires of the Chugach Mountains coming right down to the sea, carrying their glaciers with them, it was more than worth it. We raised the 13,000-foot summits at dawn and watched them appear to grow bigger as the hours slipped by and we sailed closer. By early evening we were finally in the fjord and dropping the hook in a deep secluded cove. Our anchorage reminded me of places I’ve camped at high elevations in the Alps, except that instead of an alpine meadow nestled among the peaks, there was the ocean.

|

|

Celeste alongside a glacier. |

Neptune gave us a perfect day to visit the glacier at the head of the fjord: dead calm, not a cloud in the sky, and warm. We drifted in front of the terminal face of this immense tidewater glacier for hours, taking in its towering blue wall, picking out strange shapes in the ice with our binoculars and, as the day progressed and the sun heated the ice, watching huge chunks calve into the sea with a crack and boom like the Swiss Army practicing their artillery fire near our home ashore. Around 1800, we finally started up the engine to begin our passage across the Gulf.

A nasty cross swell

The wind had picked up throughout the day and soon we had the engine off, beating down the fjord as the wind funneled up it. Once out at sea, the wind fell back into the west and we eased the sheets for our course to the Inside Passage, 470 miles away. We encountered an unexpectedly large cross swell from the south, which made Celeste roll in a nauseating fashion. Unfortunately this continued throughout the passage, which rather curtailed our celebration of our fifth wedding anniversary. The wind held on our quarter though, and we had a fast trip of only four days to reach the entrance to Peril Strait.

It turned out that we made landfall just in time. A day later, the wind built significantly and shifted into the southeast (which would have been on the nose), raising seas of 14 feet and more. Even inside the protection of the Alexander Archipelago, we had a tough time keeping to our schedule as we struggled south. We temporarily gave up and decided to wait it out once we reached a bay with hot springs only a short walk inland. Other boats collected there for the same reasons — bad weather, plus hot springs — and, in one of those small-world moments, we found ourselves reconnecting with a couple we’d met in Fiji eight years earlier during our circumnavigation.

|

|

Sea otters were just some of the wildlife seen in Alaska. |

Finally, a calm day presented itself and we had to break away from our luxurious routine of hiking, soaking in the springs and socializing. Making up for lost time, we sailed and motored 65 nm south to the town of Petersburg, slept, and kept powering another 50 nm down to Wrangell. There we paused to pick up a permit to visit a wildlife observatory where one can sit in a hide incredibly close to black (and the occasional brown) bears fishing for salmon.

The permit was valid for Saturday and this was Thursday, so we could finally slow down and make a short sail to a nearby cove. Despite the crowds one sometimes finds on the Inside Passage, we got lucky that day. The cove was tiny, with space for only one boat to swing, and we were alone with the kingfishers. It was quiet and peaceful, green with the reflections of spruce trees.

While waiting for the tidal currents to turn in our favor the next morning, we took a long hike through the rainforest at the head of the cove. Sweating along in XtraTuf rubber boots in 90 percent humidity, and struggling through mud pools, over fallen logs and through thick thorny brambles certainly made me appreciate the dry air and well-maintained trails of Switzerland, but our first sighting of a mink as well as a sense of true wilderness helped us overlook the scratches and sore muscles.

|

|

A brown bear has a successful fishing trip. |

Black bears fishing

Then it was off to the wildlife observatory. We’d heard both good and bad things: some people said it couldn’t be missed, while others had described it as frustratingly crowded and regulated. Perhaps Seth and I saw it on a slow day, but we never had to share the place with more than about 20 other people, who all were really excited to be there. I’ve always thought that wildlife conservation would never work unless people actually get to see and appreciate wild animals, so I found all the enthusiasm wonderful. And the Forest Service employees, far from being there just to enforce regulations, were genuinely interested in answering all manners of questions about a black bear’s lifespan, diet and rearing of cubs. I learned, for example, that a black bear mother kicks her cubs out of the house — so to speak — after a year, whereas a brown bear juvenile stays with his mother for at least three years. As Seth and I watched the many black bears fishing from the sides of the stream, we saw firsthand how the black bears are less tolerant of each others’ presence than the brown bears we had seen on the Alaska Peninsula. Two bears even got into a snarling disagreement over a particularly prime fishing spot.

If Seth and I hadn’t had our schedule, we would have spent at least another two days with the bears, sitting in the blind just feet away from the action, shutter fingers at the ready. As it was, we pushed on the next day and made another marathon sail all the way to Ketchikan. Then we set sail for our last Alaskan anchorage, just a few miles from the Canadian border.

|

|

Unalaska Island in a wash of summer sunshine. |

The sail from there to Prince Rupert was only 20 miles in a straight line, but we fought for every inch of the way, beating against strong southeast wind and chop. Despite leaving at dawn, we didn’t reach the customs dock until 9 p.m. But we’d made it to Canada, and from there until Vancouver Island would all be new territory for us — on our way north in 2014, we’d gone to Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands) instead of the inside archipelago.

Neptune smiled on us for the next week, delivering strong northerlies and sunshine. Celeste flew along wing and wing down the fjord-like Grenville Channel and then past more evergreen-clad shores until Princess Royal Island, home of the elusive spirit bear (an endangered white-morph subspecies of the black bear). We’d chosen anchorages where we hoped we might spot bears, but in our first one we sighted not bears but wolves! Standing nearly 3 feet tall and with the most massive paws and jaws we’d ever seen, they were magnificent creatures but unfortunately looked very sad and hungry; their ribs stood out to an alarming degree and I wondered if there just wasn’t enough prey in the area. As all of us came upon each other in the sunlit forest, I could sense their incredible intelligence and it was an open question as to who was observing whom. Without a doubt, seeing a wolf pack in the wild was the biggest highlight of our whole “best of” voyage.

After that, neither Seth nor I minded that we hadn’t seen the spirit bear. We nosed into our next anchorage, the last before we would make a straight passage to Port Angeles, happy just to be in the warm sunlight in a beautiful place. With its many scattered islets, boulders and shallow spots, it was a place we would never have tried to enter before we’d caved and gotten a chartplotter in 2014. Its secluded beauty made us very glad we’d swallowed our navigational pride. We lay stern-tied all alone among the Douglas firs and salal bushes. And then, rowing the dinghy up a nearby inlet, what should we see but a spirit bear cub, carefully watched over by his coal-black mother bear!

|

|

Seth and Ellen Leonard. |

The offshore direct route

We thought this was about as good as it could get, so the next day we headed offshore for a direct passage to Washington. Time was running out and we hoped to ride the 30- to 35-knot northwesterly that was forecast all the way down to the mouth of Juan de Fuca Strait. Unfortunately, we encountered quite the opposite of the predicted weather. A 15-knot southeasterly blew up, the current turned against us, the chop slowed us down and thick fog combined with heavy fishing traffic made us quite appreciative of our radar and AIS. After a frustrating night, the skies started to clear and the chop eased enough for us to motorsail. Finally it shifted around to the north and built to the forecast 35 knots. For all of the third day, we had an exhilarating ride, averaging nearly 8 knots among the white horses. Unfortunately it only lasted one day and then died, so we motored the last 75 miles into Port Angeles. But we’d made it, and made it within our scheduled time.

We’d made it work and still gotten to see our own “best of Alaska.”

Ellen Massey Leonard is a writer and sailor who circumnavigated with her husband Seth.

|

|

Fog flows across islands in the Aleutian chain. |